I have been spending most of my evenings watching the Tokyo Olympics. One of the most frequent questions directed to athletes who have performed outdoors is how they handle the heat. Right now, Tokyo is having highs of 90oF, with 75% humidity. That humidity is on the high side for most US cities but the temperature itself is common. Using the heat index chart from last week’s blog, we see that Tokyo’s heat index comes out to 109oF—just on the dividing line between extreme caution and danger. Danger means a high likelihood of sunstroke, muscle cramps, and/or heat exhaustion. Unlike some of us, though, most of the athletes don’t have the option to stay home and turn on the air conditioning to escape the heat. The organizers of the Olympics have tried to mitigate the heat for some competitors: they sprayed water on the sand for beach volleyball and moved the marathon race about 500 miles north of Tokyo. However, this is not much consolation to tennis players or other track and field participants who still have to compete outdoors within city limits.

Additionally, these conditions are considerably harsher than those of the last Olympics that took place in Tokyo—in 1964. The average temperature for those games was around 70oF. However, part of the reason for this drastic difference is that they were held in October and not July-August. Even so, at the time, the average high temperature in July-August hovered around 80oF.

We already knew that climate change is a serious threat to the winter Olympics but it is becoming increasingly obvious that its effects will extend to the summer games: for safety’s sake, they will either need to shift them to a later date or move them to the southern hemisphere.

Olympics aside, what about the rest of us? What dangers do we face if forced to be outside under such extreme heat conditions? National Geographic had the most straightforward description that I have encountered:

The human body has evolved to shed heat in two main ways: Blood vessels swell, carrying heat to the skin so it can radiate away, and sweat erupts onto the skin, cooling it by evaporation. When those mechanisms fail, we die. It sounds straightforward; it’s actually a complex, cascading collapse.

As a heatstroke victim’s internal temperature rises, the heart and lungs work ever harder to keep dilated vessels full. A point comes when the heart cannot keep up. Blood pressure drops, inducing dizziness, stumbling, and the slurring of speech. Salt levels decline and muscles cramp. Confused, even delirious, many victims don’t realize they need immediate help.

With blood rushing to overheated skin, organs receive less flow, triggering a range of reactions that break down cells. Some victims succumb with an internal temperature of just 104 degrees Fahrenheit (40 degrees Celsius); others can withstand 107 degrees for several hours. The prognosis is usually worse for the very young and for the elderly. Even healthy older people are at a distinct disadvantage: Sweat glands shrink with age, and many common medications dull the senses. Victims often don’t feel thirsty enough to drink. Sweating stops being an option, because the body has no moisture left to spare. Instead, sometimes it shivers.

Even the fittest, heat-acclimated person will die after a few hours’ exposure to a 95° “wet bulb” reading, a combined measure of temperature and humidity that takes into consideration the chilling effect of evaporation. At this point, the air is so hot and humid it no longer can absorb human sweat. Taking a long walk in these conditions, to say nothing of harvesting tomatoes or filling a highway pothole, could be fatal. Climate models predict that wet-bulb temperatures in South Asia and parts of the Middle East will, in roughly 50 years, regularly exceed that critical benchmark.

By then, according to a startling 2020 study in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, a third of the world’s population could be living in places—in Africa, Asia, South America, and Australia—that feel like today’s Sahara, where the average high temperature in summer now tops 104°F. Billions of people will face a stark choice: Migrate to cooler climates, or stay and adapt. Retreating inside air-conditioned spaces is one obvious work-around—but air-conditioning itself, in its current form, contributes to warming the planet, and it’s unaffordable to many of the people who need it most. The problem of extreme heat is mortally entangled with larger social problems, including access to housing, to water, and to health care. You might say it’s a problem from hell.

The Mayo Clinic provides information about how heat affects us in ways we might not have considered. Indeed, we are seeing the deadly consequences:

Extreme heat causes many times more workplace injuries than official records capture, and those injuries are concentrated among the poorest workers, new research suggests, the latest evidence of how climate change worsens inequality.

Hotter days don’t just mean more cases of heat stroke, but also injuries from falling, being struck by vehicles or mishandling machinery, the data show, leading to an additional 20,000 workplace injuries each year in California alone. The data suggest that heat increases workplace injuries by making it harder to concentrate.

“Most people still associate climate risk with sea-level rise, hurricanes and wildfires,” said R. Jisung Park, a professor of public policy at the University of California, Los Angeles and the lead author of the study. “Heat is only beginning to creep into the consciousness as something that is immediately damaging.”

The findings follow record-breaking heat waves across the Western United States and British Columbia in recent weeks that have killed an estimated 800 people, made wildfires worse, triggered blackouts and even killed hundreds of millions of marine animals.

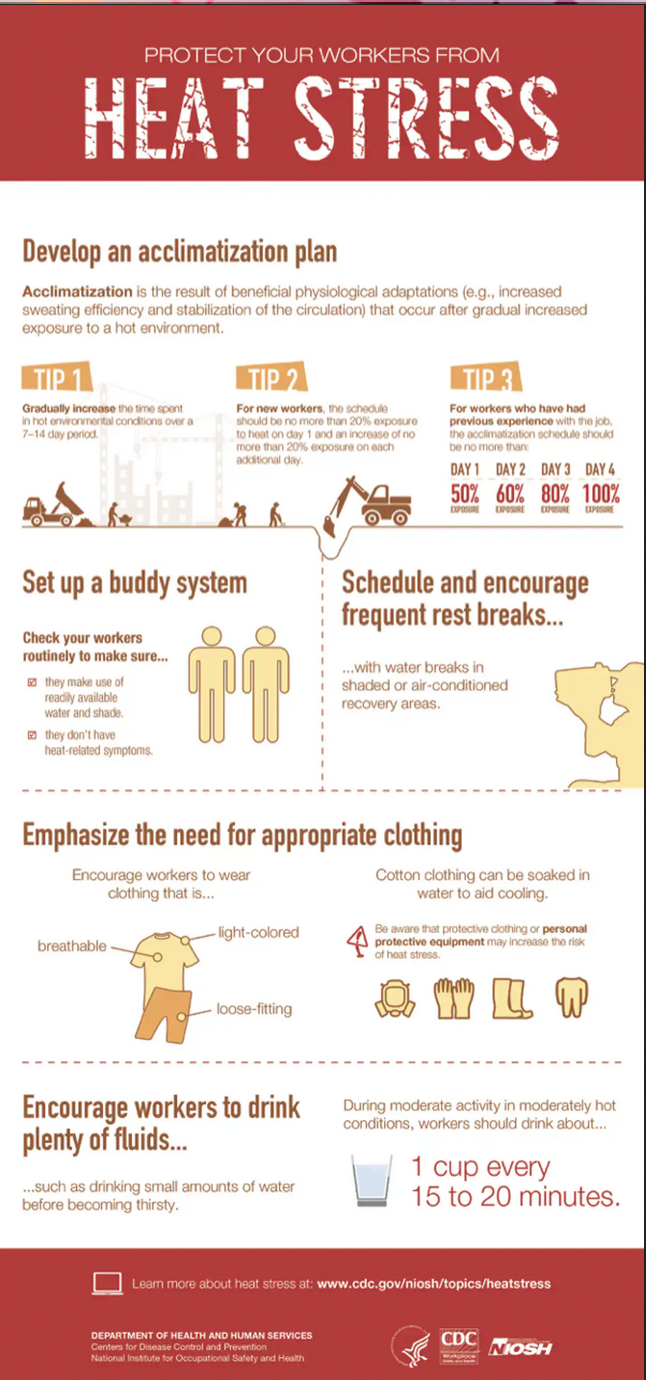

The graphic below provides some suggestions for how we can stay safer during heat waves:

While some of these seem relatively obvious, others are not necessarily as intuitive. For instance, in addition to the advice to build up a gradual heat tolerance, the part about how much water to drink (and keep drinking) is vital: don’t wait until you’re thirsty! According to the Mayo Clinic:

Thirst isn’t a helpful indicator of hydration.

In fact, when you’re thirsty, you could already be dehydrated, having lost as much as 1 to 2 percent of your body’s water content. And with that kind of water loss, you may start to experience cognitive impairments — like stress, agitation and forgetfulness, to name a few.

As we’ve discussed before, climate change means that the frequency and intensity of extreme weather will only get worse if we continue business as usual:

The study, conducted by international scientists with the World Weather Attribution group, found that the climate crisis was responsible for boosting peak temperatures by 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit (2 degrees Celsius). It also made the extreme temperatures at least 150 times more likely to occur. The research also shows that the heat wave was a 1-in-1,000-year event in our current climate, which means it’s still a rarity. But consider that it would’ve been a 1-in-150,000-year event in the pre-industrial era.

If the world heats up by another 0.8 degrees Celsius, breaching the Paris Agreement’s goal of limiting warming to 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) above pre-industrial temperatures, events like this will become almost commonplace, occurring every five to 10 years.

The report itself isn’t peer-reviewed yet, but it relies on peer-reviewed techniques that have been repeatedly used for snap analyses, including recent heat waves in Siberia and Australia, and later peer-reviewed. That gives scientists confidence in the disturbing results.

The IPCC continues to warn about the future:

Millions of people worldwide are in for a disastrous future of hunger, drought and disease, according to a draft report from the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, which was leaked to the media this week.

“Climate change will fundamentally reshape life on Earth in the coming decades, even if humans can tame planet-warming greenhouse gas emissions,” according to Agence France-Presse , which obtained the report draft.

The report warns of a series of thresholds beyond which recovery from climate breakdown may become impossible, The Guardian said. The report warns: “Life on Earth can recover from a drastic climate shift by evolving into new species and creating new ecosystems… humans cannot.

“The worst is yet to come, affecting our children’s and grandchildren’s lives much more than our own.”

But we are not just talking about the future; we’re suffering these extreme effects now. This is from just a month ago:

VANCOUVER/PORTLAND, June 30 (Reuters) – A heatwave that smashed all-time high temperature records in western Canada and the U.S. Northwest has left a rising death toll in its wake as officials brace for more sizzling weather and the threat of wildfires.

The worst of the heat had passed by Wednesday, but the state of Oregon reported 63 deaths linked to the heatwave. Multnomah County, which includes Portland, reported 45 of those deaths since Friday, with the county Medical Examiner citing hyperthermia as the preliminary cause.

By comparison all of Oregon had only 12 deaths from hyperthermia from 2017 to 2019, the statement said. Across the state, hospitals reported a surge of hundreds of visits in recent days due to heat-related illness, the Oregon Health Authority said.

In British Columbia, at least 486 sudden deaths were reported over five days, nearly three times the usual number that would occur in the province over that period, the B.C. Coroners Service said Wednesday.

Our only real remedy is to change the business-as-usual scenario we have been following—quickly! Next week, I’ll look at the timing necessary to accomplish such a transition.

Pretty! This has been a really wonderful post. Many thanks for providing these details.

good article. thanks for sharing

I am afraid of the current condition of our environment. Mostly, these heatwave, heat stroke, I am afraid to go outside. Well, not even the indoor air quality is good enough for me. I am thinking of buying an air purifier that might save me indoor. Been wondering about getting this one – https://getcomfyy.com/rigoglioso-air-purifier-sy910/

Not sure whether it’s going to help or not. If I could I might as well purify the whole world!