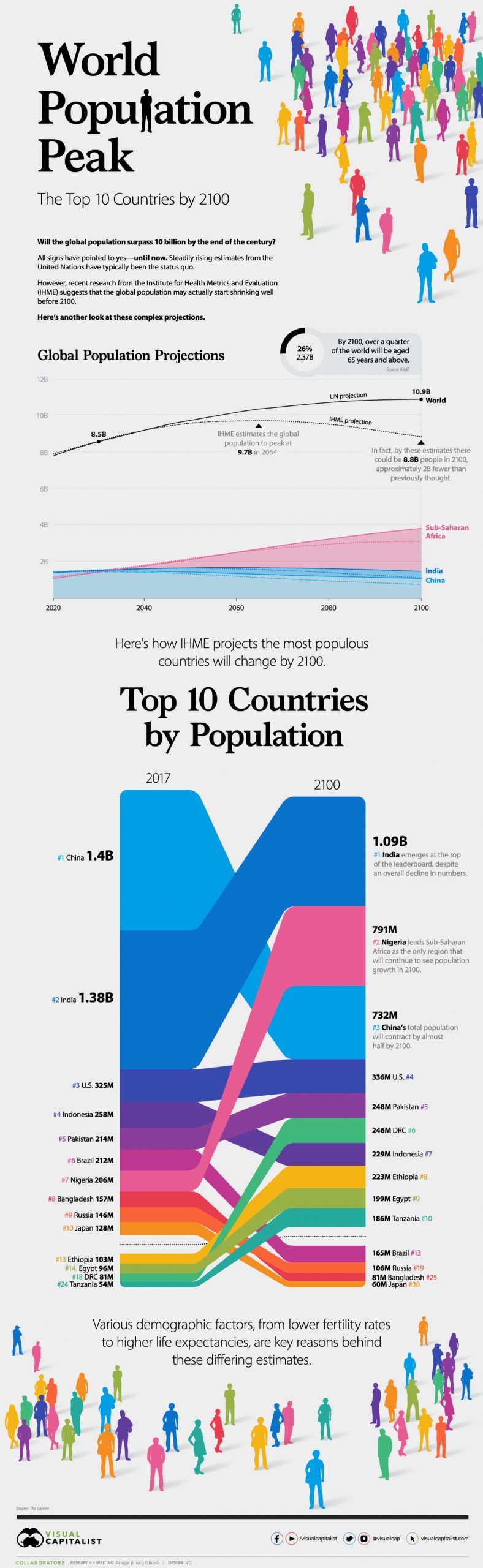

In last week’s blog, I mentioned a prediction that the global population would peak before the end of the century. This prediction was based on an analysis that was conducted by the Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) and published in The Lancet. The IHME projections differ from the UN projections that most demographers use. The two organizations use different estimates of demographic parameters such as life expectancy, migration rates, and fertility rates. Both are highly credible. Visual Capitalist, my favorite infographics site (you can find more examples by using the search box), illustrated the difference between their projections. I have included the graphic in Figure 1, along with VC’s detailed comparison of the 15 most populated countries in 2017 and those predicted to fill those slots at the end of the century. IHME’s projections also estimate that by the end of the century, about 26% of the global population will be older than 65.

The end of the century is knocking on most of our doors. Today’s children already have a life expectancy that will take them there. The world may face immense changes in the size and age of its population; humanity’s ability to adapt will be equally challenged in this and the anthropogenic climate change that is now taking place. I have repeatedly discussed the correlation between these two transitions throughout this blog (just put IPAT in the search box).

Last week’s blog focused on the global decline of fertility and childbirth and the resulting changes in population pyramids. Other demographic parameters play an important role as well.

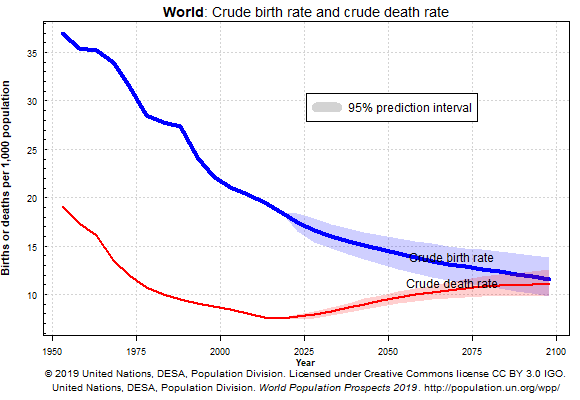

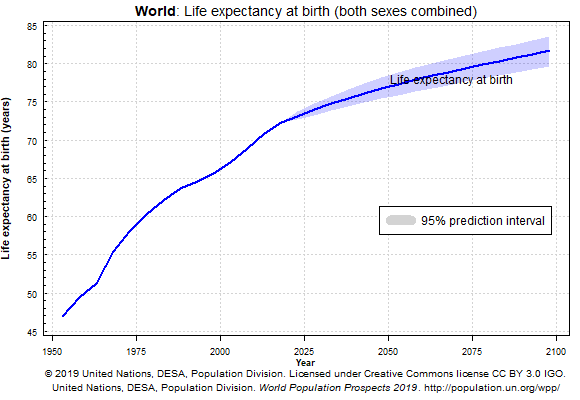

Figures 2 and 3, taken from the UN demographics site, show the changes in birth rate, death rate, and life expectancy at birth from 1950 extrapolated through the end of the century. We see the death rate reaching its minimum a few years from today, then increasing slightly until the end of the century; meanwhile, the life expectancy at birth continues to increase until the end of the century.

Figure 2

Figure 3

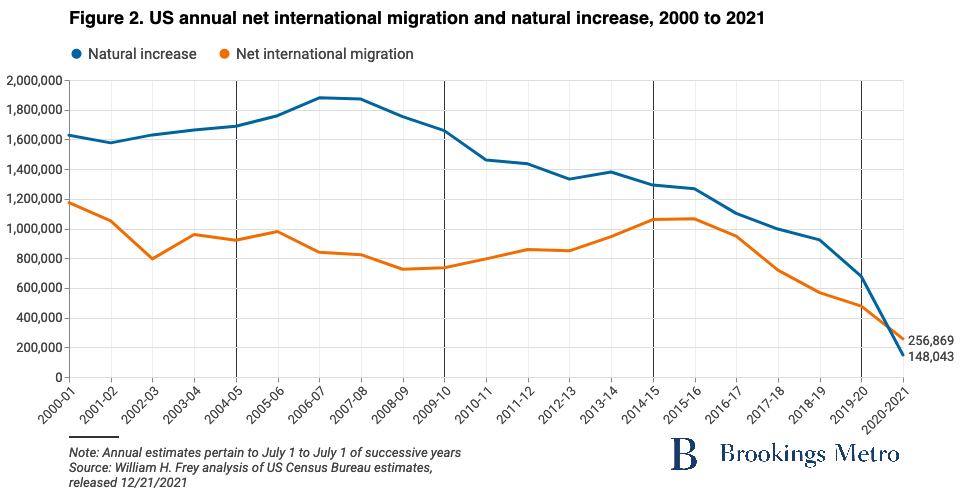

Figure 4, which looks at the demographics of the US, tracks both the “natural increase” of the internal population (births vs. deaths) and net international migration. Both have fallen in recent years, which the Brookings Institute credits to economic factors like the Great Recession, health issues like the pandemic, and policy restrictions on immigration.

China is probably the only major country to try to adjust its demographics through top-down dictates. For many years, its objective was to constrain population growth. However, the one-child campaign worked “too well” and China is now finding itself with a population pyramid like the ones I described in last week’s blog. Now, China is trying to lean in the opposite direction. According to the South China Morning Post:

China had just 12 million babies last year, down from 14.65 million in 2019, marking an 18 per cent decline year on year.

Authorities are rolling out a variety of measures to address the issue, from financial incentives to grandparenting classes.

Some regions saw births fall more than 10 per cent, while Chizhou city in Anhui province said the number of newborns in the first 10 months of the year plummeted by 21 per cent compared to a year earlier.

In cities such as Beijing, Tianjin and Jiangsu, birth rates have been below one per cent for more than two decades.

The coronavirus pandemic has dampened the willingness of women under age 30 to give birth even further, according to researchers at Renmin University, as the number of Chinese newborns dropped by 45 per cent in the last two months of 2020 compared to the final year of the controversial one-child policy in 2016.

Experts predict China’s population could go into decline as early as this year.

To address the crisis, China in May allowed couples to have three children, ending the two-child policy introduced five years earlier. Since then, authorities at both local and national levels have responded with a variety of appeals and policy changes.

In addition to “allowing” more than three children, China is taking additional steps on the provincial level: expanding maternity leave, providing financial support, creating dating service databases for singles, freezing eggs and collecting donated ones, and providing grandparenting classes. These steps do not seem to include any mention of automation.

I haven’t spoken much about the impact of the pandemic over the last two blogs. Relative to the energy transition, climate change, and population transition, we expect (or hope) that the pandemic will be shorter in duration and more limited in terms of impact. However, there is a high probability that it will result in permanent changes in our working habits. For instance, work from home (WFH) will probably become and remain more common. Such a shift might be important to various adaptation efforts. Here is what The Economist wrote:

For workers, the great wfh experiment has gone fairly well. Adjusting to the new regime was not easy for everyone—especially those living in small flats, or with children to home-school. Yet on average workers report higher levels of satisfaction and happiness. Respondents to surveys suggest that they would like to work from home nearly 50% of the time, up from 5% before the pandemic, with the remainder in the office. But people’s actual behaviour suggests that their true preference is to spend even more time in their pyjamas. How else to explain why, even in places where the threat from covid-19 is low, offices are only a third full?

Time will tell which adaptive steps will turn out to be productive in these transitions.