Figure 1 – Source: Interest.co.nz

The world is busy right now with several simultaneous global transitions that will leave an impact long after they are over. I have mentioned these transitions in earlier blogs. They include climate change, demographic saturation, COVID-19, and the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The first two are “long term,” meaning they will peak around the end of the century, while the last two are considered “short term,” meaning they are either past their peak (COVID) or approaching their peak (Russia-Ukraine). They all involve all aspects of global life and are interconnected.

Biden and NATO want to avoid any direct confrontation with the Russians to eliminate escalation to a nuclear conflict (The Fog of Peace and the Online Revolution). After all, WWI started with a “small” incident – assassination of the Austrian archduke by a Serbian nationalist. The threat of direct nuclear confrontation is not symmetrical; “the West” is trying to avoid it by replacing direct military confrontations with massive, broad economic sanctions. Meanwhile, some Russian voices are loudly making nuclear threats at any opportunity that they have.

Because of the interdependence of these global crises, it will be useful to hear voices from far ends of the world that are not directly involved in most of these crises. This piece by David Skilling from New Zealand, from which the opening picture was taken, can serve as a good example. I’m citing a few paragraphs below:

Russia’s invasion & the aggressive economic sanctions in a deeply globalized world will lead to massive global economic disruption & structural change

This is the first meaningful conflict being (partly) fought using economic instruments in a deeply integrated global economy: it is perhaps the ‘first world economic war’, with effects stretching from New Zealand and Singapore to the Middle East and Europe. We are in uncharted waters.

Whereas the physical conflict in Ukraine will eventually end, this economic war will be very long-lived – it has its own political logic. The formal sanctions will be in place for a long time – at a minimum, until the Russian invasion is reversed, and perhaps Mr Putin is gone. But even if/when sanctions are lifted, the drive for economic independence from Russia (notably in energy) will continue. And many companies will be reluctant to return rapidly to the Russian market due to stakeholder pressure.

More broadly, precedent has been set for the use of sweeping economic sanctions. The US, Europe, and others will increasingly use trade, investment, and technology instruments, in strategic competition with their rivals.

The question that I would like to raise in this blog is this: Is it feasible to expand tactics from the “first world economic war” to fight the other global threats that we are facing? This is a complicated question that I will be likely to revisit in future blogs. In this blog, I would like to focus on the difficulties associated with the data in which these global crises overlap.

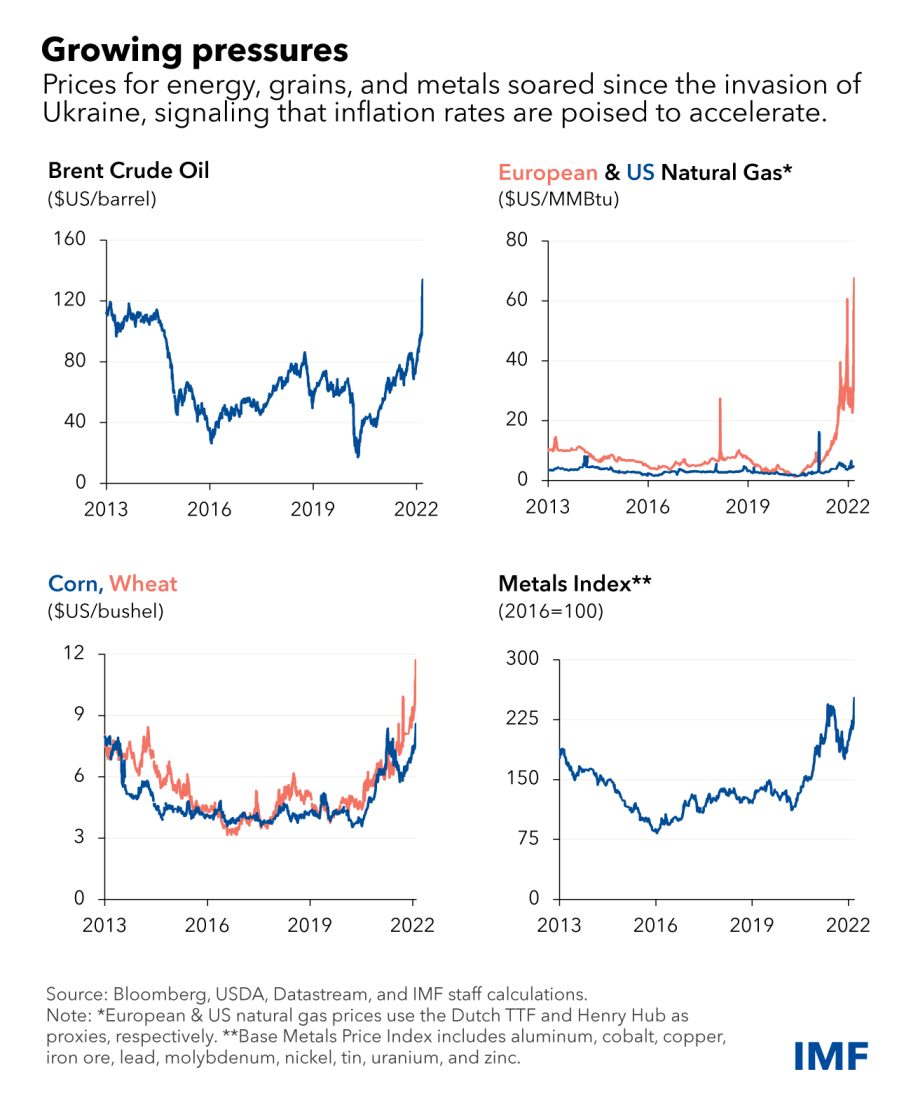

Figure 2 shows some of the recent economic indicators over the last few years. The COVID-19 pandemic started toward the end of 2019. Shortly after its start, we saw a sharp decline in energy prices because of the sharp decline in demand. As we approached the end of 2021, most people (in developed nations) got vaccinated. The pandemic is still around with different variants; however, most people and countries have learned how to live with it and a relatively quick return to “normal” life started to take place. Overall demand for everyday supplies started to outpace supply and issues with supply triggered relatively sharp, global increases in inflation. The Russian invasion of Ukraine took place at the end of February 2022. However, the Russian army’s encirclement of Ukraine started a few months earlier. The outcry against the move rather quickly triggered major economic sanctions. As I have mentioned, Russia is a petrostate that contributes to the global supply of fossil fuels. European countries are especially vulnerable to disruptions in this supply and the energy prices are determined globally. Energy drives much of our economic activity. One can see sharp inflationary spikes as we start 2022 but these started before the invasion.

Figure 2 – Global impact of selected indicators

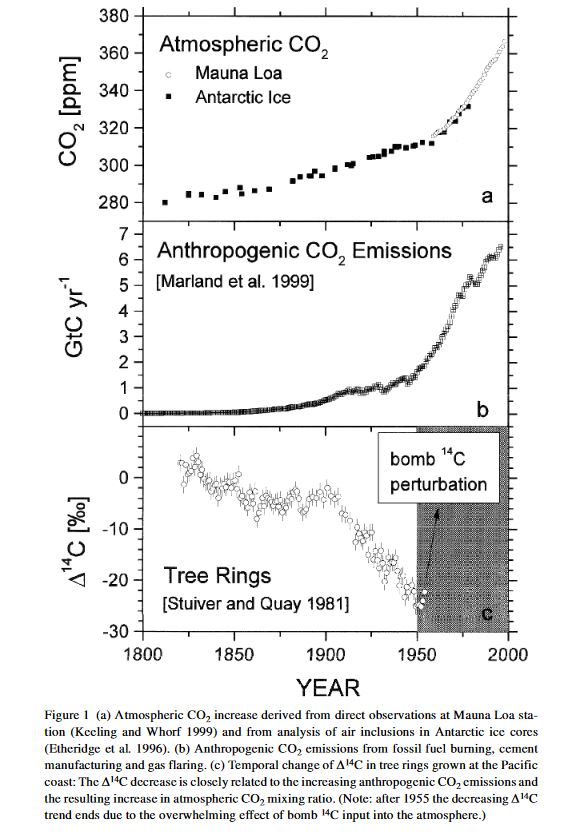

As I have mentioned, it is too early to separate the COVID-19-based impact on prices that have to do with supply chain issues from those related to the economic sanctions that were imposed on Russia. Similar issues can be traced to the anthropogenic impacts on climate change that I discussed in an earlier blog (January 9, 2018 – “Natural” or “Anthropogenic”? – Climate Change). The original figure and references from that blog are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3 – Carbon emissions and 14C atmospheric tracing

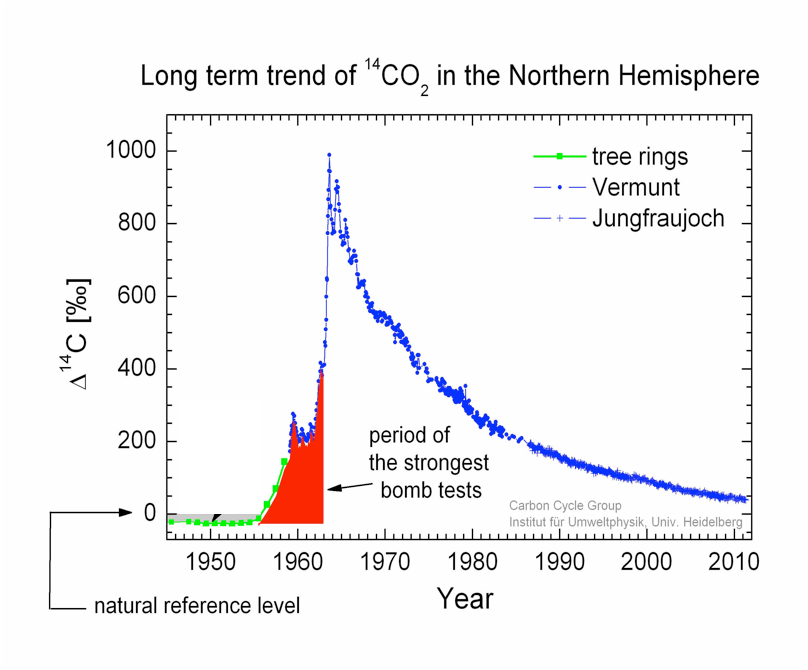

As I explained then, the atmospheric decline in carbon-14 is probably the strongest indicator of the anthropogenic origin of climate change that comes from the burning of fossil fuels. However, early atmospheric tests of nuclear weapons completely masked such impacts. Some data before the beginning of nuclear testing and more data after the 1960s strongly confirmed the decline of 14C related to the anthropogenic burning of fossil fuels as shown in Figure 4. More time is needed to isolate the impacts of the sanctions on the supply chain.

Figure 4 – More recent measurements of 14C

More time is also needed to judge the effectiveness of the sanctions on Russian behavior in Ukraine. Hopefully, we will be able to figure out if such sanctions can expand to be a global governing tool to minimize global harm such as anthropogenic climate change. More on that in the next blogs.