Last week’s blog focused on globalization. Per definition, we are part of the global picture and from this perspective, we have a direct interest in whatever global conflict emerges. Two of our present global conflicts can serve as guides: the Russian invasion of Ukraine and climate change. Almost all of us are directly involved in both, albeit in different ways.

Russia and Ukraine are obviously the most directly involved in the war. Their soldiers are killing and wounding each other, and the Russian army is directly involved in the slaughter of Ukrainian citizens and destruction of the country. Yesterday, Russia celebrated Russian Victory Day, following the signing of the German Instrument of Surrender late in the evening on May 8, 1945 (after midnight). Almost everybody expected an announcement focused on the war in Ukraine. President Putin defended the Russian activity but didn’t offer any guidance. How believable an announcement would have been depends on the perspective of the listeners. Misinformation during wars is common. It’s one of the most important tools that armies use. Recently, the New York Times tried to follow the different information on common events that Russians, the Ukrainians, and the rest of the world follow on the state of this war. Below are two short paragraphs from that piece:

To Western audiences, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has unfolded as a series of brutal attacks punctuated by strategic blunders. But on Russian television, those same events were spun as positive developments, an interpretation aided by a rapid jumble of opinion and falsehoods.

Much of Russian news media is tightly controlled by the Kremlin, with state-run television working as a mouthpiece for the government. Critical reporting about the war has been criminalized.

The rest of us follow much more competitive sources of information.

Significant parts of the world (many of which I included in the label “the West” in previous blogs) strongly support Ukraine in this conflict. However, most refuse to get directly involved in a war with Russia because they fear uncontrolled escalation and possible existential consequences. Instead, they have decided to support Ukraine through economic sanctions on Russia and military equipment delivery to Ukraine. However, our knowledge of the impacts of these sanctions on Russia depends to a large degree on the information coming from Russia, making it difficult to judge the truth. The Economist believes that Russia is doing well:

In early April we pointed to preliminary evidence that the Russian economy was defying predictions of collapse, even as Western countries introduced unprecedented sanctions. Recent data further support this view. Helped along by capital controls and high interest rates, the ruble is now as valuable as it was before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in late February (see top chart). Russia appears to be keeping up with payments of its foreign-currency bonds.

Al Jazeera has a different perspective:

The ongoing geo-economic conflict between Russia and the West is a complicated one, surrounded by nearly as much disinformation and misinformation as the war in Ukraine itself. As such, both parties are confidently claiming to have the upper hand. But looking at the evidence at hand objectively, it becomes clear that the Kremlin is in retreat.

As to climate change, all of us are directly involved and our future generations are going to be even more so. It has long been understood by many that one cannot solve the climate change threat without addressing the issue of misinformation that drives deniers (see my “Three Shades of Deniers” blog from September 3, 2012). Science News published an article about this last summer:

Over the last four decades, a highly organized, well-funded campaign powered by the fossil fuel industry has sought to discredit the science that links global climate change to human emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases. These disinformation efforts have sown confusion over data, questioned the integrity of climate scientists and denied the scientific consensus on the role of humans.

Such disinformation efforts are outlined in internal documents from fossil fuel giants such as Shell and Exxon. As early as the 1980s, oil companies knew that burning fossil fuels was altering the climate, according to industry documents reviewed at a 2019 U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Oversight and Reform hearing. Yet these companies, aided by some scientists, set out to mislead the public, deny well-established science and forestall efforts to regulate emissions.

A recent PBS short series emphasizes the connection focusing on the role that oil companies—specifically the American Petroleum Institute, Exxon-Mobile, and the Koch brothers—have played in emphasizing uncertainty (“scientists don’t agree”) so as to negate any attempts at policy changes.

Recently, some oil companies have claimed a change of heart and made promises of net-zero emissions but it’s always good to look at the details:

What Does Net Zero Emissions Mean for Big Oil? Not What You’d Think

BP, Shell, and other companies say they’ll address climate change. But their pledges fall far short of what’s needed to meet global climate goals. By Nicholas Kusnetz

Bernard Looney, BP’s new chief executive, stood behind the podium in a London hotel in February and announced that the company would dramatically shift the way it did business.

Framed by a multi-hued green background, Looney described a transformation of BP’s structure and operations that would steer the oil giant to spend more on clean energy and less on fossil fuels. By 2050, he said, BP would achieve net-zero greenhouse gas emissions, joining a growing list of governments and corporations committed to tackling climate change.

Looney’s speech launched a rapid-fire game of one-upmanship among Europe’s largest oil and gas companies. Within three months, Total and Royal Dutch Shell had announced their own plans to reach net-zero emissions by 2050, building on previous pledges to increase spending on low-carbon energy sources like wind, solar and biofuels.

Two of their American counterparts, ExxonMobil and Chevron, have also announced goals to reduce climate-warming pollution, although much more modest ones.

But many of the pledges are misleading, and misrepresent how much the oil giants are changing. Most glaring is that none of the companies has committed to cut its oil and gas output over the next decade, the simplest and most reliable way—one might say the only way—to cut emissions, and a must if the world is to avoid dangerous warming. In fact, the stated net-zero “ambitions,” as the companies generally call them, do not require that greenhouse gas emissions fall to zero at all. They rely instead either partly or largely on capturing or canceling out these emissions with unproven technologies and reforestation at a questionable scale.

Meanwhile, through industry associations the companies have continued to lobby against policies that would hasten a shift away from oil and gas: All the companies, for example, retain membership in the American Petroleum Institute (API), which has lobbied against incentives for electric vehicles, supported the Trump administration’s rollback of methane regulations and backed expanded drilling in the Arctic.

In other words, “net-zero” does not actually mean cutting down on fossil fuel emissions. It’s based on finding emission sinks to balance the damage.

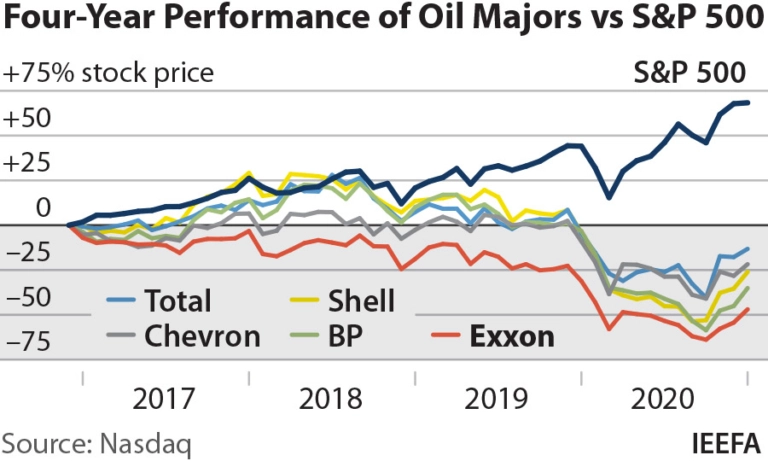

We can tell from their stock prices that—overall, oil companies aren’t doing well with their present policies. Figure 1 shows the performance of a few large oil companies over the last 5 years, compared to the performance of the S&P 500. Maybe these numbers will prompt change in the form of an energy transition, even if just for a better bottom line.

Figure 1 – Stock performance over major oil companies compared to S&P 500

Last year, before the Russian-Ukrainian war changed power balances in oil, the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA.Org) warned about the continuing business as usual for oil companies:

Rising prices may give new life to outdated strategies. Each oil uptick has prompted ExxonMobil and like-minded companies to double down on the failed strategy of heavy capital spending on new oil and gas supplies. But until prices rise dramatically and persistently, the oil industry can’t find a sustainable business model in simply depleting and replacing reserves. In 2018, global oil prices stood at $71 per barrel, almost $30 more than in 2020, yet the energy sector still finished in last place in the S&P 500.

Rising prices could lull investors into complacency. The oil and gas industry’s financial woes have galvanized investors into pressing for changes in oil industry governance and strategy. Some companies have responded by diversifying their business models—shifts that were healthy for the companies and rewarded by shareholders. But rising prices could derail this investor pressure, discouraging healthy scrutiny, weakening transparency, and dissipating the momentum of the energy transition.

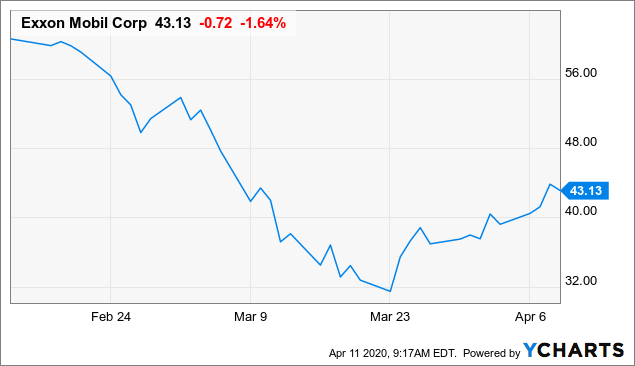

Unsurprisingly, the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the coming decisions by the European Union to accelerate their “independence” from Russian oil have caused a sharp increase in the international oil price. This has resulted in some improvements in the performance (increase in profits) of the oil companies, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2 – Recent ExxonMobil stock price

Next week, I will discuss where I see the oil companies’ net-zero commitments going.