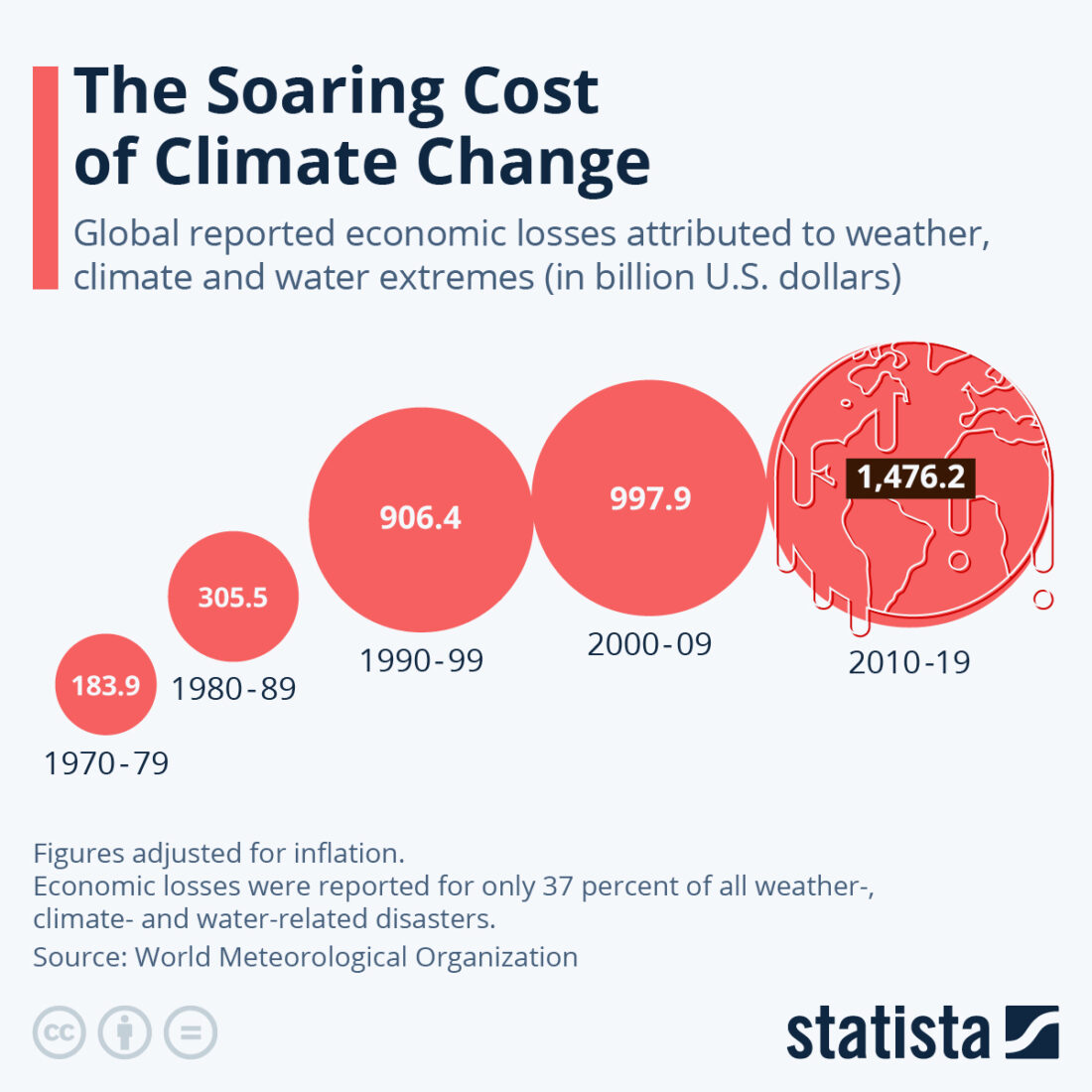

(Source: Statista; Data based on Word Meteorological Organization)

The data are coming with the comment that “Economic losses were reported for only 37% of all weather, climate- and water related disasters. 2025 global GDP is estimated at 114 Trillion US$. We are talking big numbers here.

This blog will focus on the global aspects of the threats and the actions of the Trump administration to confront them.

Global threats, such as climate change, require global mitigation. Mitigation is a slow process, so increasing threats require global adaptation. But adaptations in most cases are local. The world is a very uneven place, so, financing remedies to global threats needs to follow. It does not. Below is an AI summary (through Google) of the global financial stresses between developed and developing countries:

Developed vs. developing countries

A major source of global tension is the historical responsibility for causing climate change and the resulting financial obligations.

- “Polluter pays” principle: Developing nations argue that developed countries, which are responsible for the bulk of historical greenhouse gas emissions, should bear the largest share of the financial burden.

- Self-interest shapes spending: Developed countries, however, have different motivations. Investing in mitigation projects in a developing country yields a global benefit that all countries share. In contrast, funding adaptation primarily benefits the recipient country, which may reduce the incentive for politicians in donor countries to favor adaptation spending.

- The $100 billion promise: Developed countries pledged to provide $100 billion per year in climate finance to developing nations by 2020. They reported exceeding this goal in 2022, but the pledge was still met two years late, and only a fraction of the total went to the poorest countries.

- The heavy burden on developing nations: When compared to their GDP, least developed countries (LDCs) face the heaviest costs for climate action. For some, addressing climate change could require up to 40% of their GDP, far exceeding what is provided in international assistance.

Developing countries and domestic finance

-

Developing nations cannot rely on international assistance to cover all climate-related investments. Nearly half of the required funding needs to come from domestic sources.

-

For the most vulnerable nations, particularly Least Developed Countries (LDCs) and Small Island Developing States (SIDS), a greater share of international funding often comes as grants to avoid further increasing their debt burden.

-

In contrast, many middle-income developing countries receive a higher proportion of funding through loans, which can worsen debt problems.

Climate change impact doesn’t strike on its own. Anthropogenic (originating in human activities) impacts intensify natural weather patterns. Climate disasters took place before humans were around, and atmospheric turbulence is observed on planets where life is not observed. Attributions to anthropogenic causes are key to the mitigation of such events. A key earlier blog that describes the issue of attributions, is the one published on October 3, 2017, under the title of “Doomsday: Attributions.” I strongly recommend looking at that background issue.

The rest of the blog will focus on quantifying specific sectors:

- Global Insurance (Natural disasters caused $135 bn in economic losses in first half of 2025: Swiss Re):

Natural disasters caused $135 billion in economic losses globally in the first half of 2025, fueled by the Los Angeles wildfires, reinsurer Swiss Re said Wednesday.

Swiss Re, which serves as an insurer of insurance companies, said first half losses were up from the $123 billion in the first half of 2024.

The Zurich-based reinsurance giant estimated that of this year’s first half losses, $80 billion had been insured — almost double the 10-year average, in 2025 prices.

The Los Angeles blazes in January constitute the largest-ever insured wildfire loss event by far, reaching an estimated $40 billion, said Swiss Re.

It said the “exceptional loss severity” of the fires was down to prolonged winds, a lack of rainfall and “some of the densest concentration of high-value single-family residential property in the US”.

Climate change could be responsible for a 380% increase in foreclosures by 2035, according to research firm First Street’s most recent National Risk Assessment.

The assessment also predicts the economic impact of these foreclosures on lenders, and the potential losses could be staggering. First Street’s analysis expects mortgage lenders to lose $1.2 billion in natural disaster-related foreclosures in 2025. That figure is expected to go as high as $5.4 billion by 2035. Losses that big could change how mortgage lenders calculate risk.

Currently, most mortgage lenders consider the borrower’s income, credit history, and debt load as the biggest potential risks in processing loan applications. First Street believes lenders may be forced to consider how extreme weather events could elevate their risk level when making underwriting decisions. Most banks don’t consider the possibility of climate-change-driven foreclosure risk in making loan decisions. First Street assessment suggests they should.

Swiss Re said losses from wildfires had risen sharply over the past decade due to rising temperatures, more frequent droughts and changing rainfall patterns — plus greater suburban sprawl and high-value asset concentration.

“Most fire losses originate in the US and particularly in California, where expansion in hazardous regions has been high,” it said.

- Corporations

- Net Zero Targeting (https://www.cbc.ca/news/business/net-zero-corporate-climate-targets-1.7338799)

In what is becoming something of a trend, a number of companies are abandoning their carbon emissions targets — in a year scientists have determined is likely to end up being the hottest on record. Earlier this month, Volvo announced it was dropping its goal of having a fully electric lineup of vehicles by 2030. In the summer, Air New Zealand said it was abandoning a pledge to reduce its emissions by about 29 per cent by 2030. And in March, Shell announced it was easing its target of reducing the total “net carbon intensity” of all the energy products it sells by 20 per cent. “I don’t think [the trend] is really new, but given the state of the world, it’s more apparent,” said Charles Cho, a professor of sustainability accounting and the Erivan K. Haub Chair in business and sustainability at the Schulich School of Business at York University in Toronto. The message from a lot of these companies is that meeting their climate targets has become too costly, a theme emphasized by some American banks last month at NYC Climate Week, an annual gathering for organizations to discuss global warming. After more than 190 countries signed the Paris Accord in 2015 — codifying an international push to keep global temperatures well below 2 C warming from pre-industrial levels — many companies made bold climate pledges. A lot of them promised deep emissions cuts. Many said they’d reach net zero — that is, modifying their operations so their net emissions were zero — by 2030. But Cho says a lot of them didn’t really specify how they would get there. And now, a decade later, in the absence of any meaningful enforcement for countries and companies alike, many companies are realizing those goals are unattainable. “I think there was a rush to make those targets visible on their [corporate] reports, but … I think they spoke too fast,” said Cho. The stated reasons for these retrenchments vary. For example, Air New Zealand has blamed its decision on poor access to efficient planes and sustainable aviation fuel. Volvo has cited stagnant demand for electric vehicles and inadequate charging networks, while Shell emphasized continuing demand for oil and gas and uncertainty about the speed of the global energy transition.

- Balancing Short Term Profit with Long Term Responsibilities (https://oilprice.com/Energy/Energy-General/2-Trillion-Funding-Gap-Casts-Shadow-over-Energy-Transition.html):

Investments in the energy transition are falling way short of what is needed for its success. The fresh warning comes from BlackRock, which said annual investments in the shift away from hydrocarbons need to almost double from their current record levels. But it’s getting less likely this would ever happen.

In a new edition of its Investment Institute Transition Scenario, the bank said that moving the transition forward would require more money from both public and private sources and that, for its part, would require “alignment between government action, companies and partnerships with communities,” according to Michael Dennis, head of APAC Alternatives Strategy & Capital Markets at BlackRock, as quoted by CNBC.

BlackRock mentioned the $4-trillion figure as the necessary sum to be invested in the transition annually back in December when it released the original IITS. The amount was as impressive as it is now, not least because it was double the amount of earlier investment estimates. What makes it even more impressive is the fact that last year’s record transition investments came in at less than half that, at $1.8 trillion.

However, impacts of governments fluctuate and corporations are aware of that. Inertia plays an important role in running successful corporations. The concept of ESG (environmental, social, and governance) investments is probably the best indicator for the susceptibility of corporations to societal changes. I wrote about it in an earlier blog (February 18, 2025), with the following summary:

The ESG (environmental social governance) concept has appeared frequently throughout this blog. Two of the more recent blogs are from August 16, 2022, and March 28, 2023. Specific issues that ESG addresses are marked on the figure above, including aspects of DEI. You can find more entries through this blog’s search box. The issue that I am addressing in this blog is the new Trump administration’s attitude toward the concept and its impact on businesses. I’m especially interested in the differences between and similarities to the administration’s attitude toward DEI that was discussed in last week’s blog. In the March 28, 2023 blog, I tried to make the case that politicizing ESG means politicizing our future.

Below is how inertia is playing a role around these shifts:

The vast majority of large U.S. companies are maintaining or even increasing investments in ESG initiatives, as most executives view sustainability as a driver of competitive advantage and growth, but many are talking less about it publicly in the face of growing political and regulatory scrutiny, according to a new survey released by business sustainability ratings and solutions provider EcoVadis. For the report, “2025 U.S. Business Sustainability Landscape Outlook,” EcoVadis surveyed 400 executives responsible for business and operational decision-making at companies with over $1 billion in revenues in industries ranging from consumer and industrial, to technology and services.

The next blog will focus on what the present Trump administration is doing to the US ability to mitigate and adapt to global threats.