Last week’s blog ended with documentation of the COP27’s late unanimous agreement to generate a special fund to help developing countries to cope with adaptation to damage that climate change inflicts. Below is the exact language that the UNFCCC is using to describe the nature of the agreement:

UN Climate Change News, 20 November 2022 – The United Nations Climate Change Conference COP27 closed today with a breakthrough agreement to provide “loss and damage” funding for vulnerable countries hit hard by climate disasters.

“This outcome moves us forward,” said Simon Stiell, UN Climate Change Executive Secretary. “We have determined a way forward on a decades-long conversation on funding for loss and damage – deliberating over how we address the impacts on communities whose lives and livelihoods have been ruined by the very worst impacts of climate change.”

Creating a specific fund for loss and damage marked an important point of progress, with the issue added to the official agenda and adopted for the first time at COP27.

Governments took the ground-breaking decision to establish new funding arrangements, as well as a dedicated fund, to assist developing countries in responding to loss and damage. Governments also agreed to establish a ‘transitional committee’ to make recommendations on how to operationalize both the new funding arrangements and the fund at COP28 next year. The first meeting of the transitional committee is expected to take place before the end of March 2023.

Parties also agreed on the institutional arrangements to operationalize the Santiago Network for Loss and Damage, to catalyze technical assistance to developing countries that are particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of climate change.

As is described here, the all-important implementation of this agreement has been deferred until COP28, with the meeting of an established “transitional committee” to happen no later than March 2023. We obviously will return to this issue.

As promised, this blog will address the question of what the developing countries propose to do in case the funds are made available to them. Next week I will focus on the same issue from the perspective of the developed countries involved.

This blog will focus on a few examples of actual actions of some developing countries and on the related question of whether money from developed countries should be the only source of financing available to confront these issues.

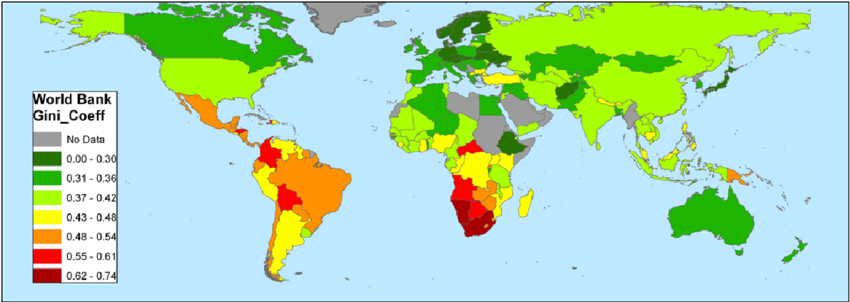

An earlier blog (May 14, 2019), written by my students, addresses the contributions of two important parameters of global carbon emissions: the environmental Kuznets curve, which determines a country’s stage in its economic development (strongly energy-dependent heavy industry or relatively energy-light services) and the income distribution measured through the Gini coefficient. I suggest that you go back to that blog for a refresher on what these two parameters mean. The Gini coefficient is an income distribution parameter that ranges between 0 and 1 (or in percent, between 0 and 100%). 0 indicates perfect income distribution while Gini = 1 indicates all the income is concentrated in the hands of a single person). Putting this in less extreme terms, a small Gini indicates a relatively broad income distribution while a relatively large coefficient indicates that fewer hands hold most of the income. Figure 1 shows a global map of the distribution of the Gini coefficients with the darker colors indicating a more unequal distribution. For more detailed, recent values of the Gini coefficient, one can go to the original World Bank publication. The most recent values from the World Bank are available under the Gini index section of the World Bank website..

Figure 1 – Map of global Gini coefficients reported by the World Bank (Source: ResearchGate)

One can see from Figure 1 that uneven income distribution is less of a problem in richer countries. Many of the rich countries such as most of Europe, Canada, Australia, and Japan enjoy relatively broad income distribution. A handful of very poor countries such as Afghanistan and Ethiopia also enjoy a “healthy” distribution, meaning that most people there are poor.

A high Gini coefficient is seen in the southern parts of Africa and South and Central America. One can deduce from such maps that more effective taxation of higher income brackets might be an effective way to increase these countries’ resources to fight ecological disasters. I will return to this issue in the following blog when I deal with the role of rich countries in fighting the climate change crisis.

I will now shift to a few cases of relatively poor countries that have already found the resources to make major progress in shifting their development to a more sustainable landscape. I have also asked one of my students to write a guest blog that will include other examples of what countries that currently lack the resources to fight climate change intend to do once such resources become available.

The efforts below represent major steps to enhance sustainability. First, we look at two small developing countries: Belize and Nepal. Meanwhile, so far, an agreement about the joint environmental impacts between three large developing countries (Brazil, Indonesia, and Congo) that host more than half of the global forests has no source of funding. Finally, there’s an agreement between a group of developed countries to help Indonesia in its transition away from coal:

Belize cut its debt by fighting global warming:

TURNEFFE ATOLL, Belize — Belize faced an economic meltdown. The pandemic had sent it into its worst ever recession, putting the government on the brink of bankruptcy.

A solution came from unexpected quarters. A local marine biologist offered Prime Minister Johnny Briceño a novel proposal: Her nonprofit would lend the country money to pay its creditors if his government agreed to spend part of the savings this deal would generate to preserve its marine resources.

For Belize, that meant its oceans, endangered mangroves and vulnerable coral reefs.

Nepal grew back its forests:

“You see that? They were barren mounds of red mud 15 years ago,” said the man, Khadga Bahadur Karki, 70, tears of pride fogging up his glasses. “These trees are more than my children.”

This transformation is visible across Nepal, thanks to a radical policy adopted by the government more than 40 years ago. Large swaths of national forest land were handed to local communities, and millions of volunteers like Mr. Karki were recruited to protect and renew their local forests, an effort that has earned praise from environmentalists around the world. But the success has been accompanied by new challenges — among them addressing the increase in potentially dangerous confrontations between people and wildlife.

Community-managed forests now account for more than a third of Nepal’s forest cover, which has grown by about 22 percent since 1988, according to government data. Independent studies also confirm that greenery in Nepal haas sprung back, with forests now covering 45 percent of the country’s land.

Brazil, Indonesia, and Congo signed a rainforest protection pact:

SHARM EL SHEIKH, Egypt — The three countries that are home to more than half of the world’s tropical rainforests — Brazil, Indonesia and the Democratic Republic of Congo — are pledging to work together to establish a “funding mechanism” that could help preserve the forests, which help regulate the Earth’s climate and sustain a variety of animals, plants, birds and insects.

The agreement, announced on Monday and signed by ministers from the three countries, said they would cooperate on sustainable management and conservation, restoration of critical ecosystems and creation of economies that would ensure the health of both the people and the forests.

The plan has no financial backing of its own and was more of a call to action than a strategy for how to achieve its goals.

US, Japan, and partners mobilized $20 billion to help Indonesia to transition away from coal

NUSA DUA, Indonesia/SHARM EL-SHEIKH, Egypt, Nov 15 (Reuters) – A coalition of countries will mobilise $20 billion of public and private finance to help Indonesia shut coal power plants and bring forward the sector’s peak emissions date by seven years to 2030, the United States, Japan and partners said on Tuesday.

The Indonesia Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP), more than a year in the making, “is probably the single largest climate finance transaction or partnership ever”, a U.S. Treasury official told reporters.

The Indonesia JETP is based on last year’s $8.5 billion initiative to help South Africa more quickly decarbonise its power sector that was launched at the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow by the United States, Britain and European Union.

To access the programme’s $20 billion worth of grants and concessional loans over a three- to five-year period, Indonesia has committed to capping power sector emissions at 290 million tonnes by 2030, with a peak that year. The public and private sectors have pledged about half of the funds each.

As I’ve mentioned before, great inequalities are major impediments to addressing climate change on both global and local levels. The next blog will try to address the issues on the rich countries’ level.

It is interesting to see what developing countries propose to each other. I find it surprising that developing countries offer assistance to one another. I didn’t think they would interact.

I find it interesting to see the focus on what developing countries propose, as it is raised as a question here. Seeing developing countries help each other is what surprised me since it appears as unusual. I think this because I thought that most countries wouldn’t interfere with one another.

I think it is interesting to see how other countries and territories are helping each other preserve and save the less fortunate. This comes as a surprise to me considering that I had thought that most territories hadn’t concerned themselves with the business of other territories unless something dangerous happened or could be happening.