Sustainability in NYC

In mid-April, the New York City Council passed an incredibly important piece of legislation regarding our city’s sustainability, calling for landlords to upgrade the built environment:

New York City Passes Historic Climate Legislation

The Climate Mobilization Act lays the groundwork for New York City’s own Green New Deal.

By Alexander C. Kaufman

The legislation sets emissions caps for various types of buildings over 25,000 square feet; buildings produce nearly 70% of the city’s emissions. It sets steep fines if landlords miss the targets. Starting in 2024, the bill requires landlords to retrofit buildings with new windows, heating systems and insulation that would cut emissions by 40% in 2030, and double the cuts by 2050.

“This legislation will radically change the energy footprint of the built environment and will pay off in the long run with energy costs expected to rise and new business opportunities that will be generated by this forward thinking and radical policy,” said Timur Dogan, an architect and building scientist at Cornell University.

The Climate Mobilization Act’s other components include a bill that orders the city to complete a study over the next two years on the feasibility of closing all 24 oil- and gas-burning power plants in city limits and replacing them with renewables and batteries. Another that establishes a renewable energy loan program. Two more that require certain buildings to cover roofs with plants, solar panels, small wind turbines or a mix of the three. And a final bill that tweaks the city’s building code to make it easier to build wind turbines.

The cost to landlords is high. The mayor’s office estimated to The New York Times that the total cost of upgrades needed to meet the new requirements would hit $4 billion.

It reads a lot like a NYC-specific Green New Deal (GND) (see the February 19, 2019 blog). This is appropriate, given that New York’s own Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez is the congresswoman people most identify with the GND (cosponsored by Sen. Ed Markey, D-Mass). The legislation sounds great but we have lived through these kinds of initiatives before; some regulations are more effective than others. I used to teach a course at my school that focused on New York City’s efforts to mitigate and adapt to climate change. For example, this is from a class file from Spring 2010:

PlaNYC Energy Initiatives

On Earth Day, 2007, Mayor Bloomberg released plaNYC, a sustainability plan for the City’s future. The plan is designed to lower our collective carbon footprint while also compensating for population growth and improving the city as a whole. Here we address its fourteen-point plan for energy and analyze its progress thus far.

Sustainability at CUNY

I work within the City University of New York (CUNY) — the largest urban university in the US. Following Mayor Bloomberg’s announcement, CUNY formed a sustainability task force:

The CUNY Sustainability Project was given institutional clarity and impetus through the acceptance by Chancellor Goldstein on June 6, 2007 of Mayor Bloomberg’s ’30 in10′ challenge. This challenge will motivate New York City’s public and private universities to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions 30% by 2017. CUNY is committed to investing the resources necessary to construct, retrofit and maintain more sustainable and green facilities.

You can follow the university’s progress in this area here.

While a number of UC schools feature in the Sierra Club’s list of the country’s 200 most sustainable schools (see last week’s blog), CUNY campuses are nowhere to be found. In fact, the top NYC school on the list is St. John’s University at #50, with Columbia University coming in at #90.

We (New York and CUNY) can and should do much better. To my knowledge, nobody has ever tried to use schools as laboratories where they could correlate economics with energy transition. In theory, in addition to converting the campus itself into an environmentally friendly institution, a school could train its graduates to perform such conversion jobs —thus enhancing their qualifications for satisfying employment once they leave school.

I teach physics in my school; it’s an experimental science:

experimental science

- Diligent inquiry or examination in seeking facts or principles; laborious or continued search after truth; as, researches of human wisdom; to research a topic in the library; medical research.

- Systematic observation of phenomena for the purpose of learning new facts or testing the application of theories to known facts; — also called scientific research. This is the research part of the phrase “research and development” (R&D).

Note: The distinctive characteristic of scientific research is the maintenance of records and careful control or observation of conditions under which the phenomena are studied so that others will be able to reproduce the observations. When the person conducting the research varies the conditions beforehand in order to test directly the effects of changing conditions on the results of the observation, such investigation is called experimental research or experimentation or experimental science; it is often conducted in a laboratory. If the investigation is conducted with a view to obtaining information directly useful in producing objects with commercial or practical utility, the research is called applied research. Investigation conducted for the primary purpose of discovering new facts about natural phenomena, or to elaborate or test theories about natural phenomena, is called basic research or fundamental research. Research in fields such as astronomy, in which the phenomena to be observed cannot be controlled by the experimenter, is called observational research. Epidemiological research is a type of observational research in which the researcher applies statistical methods to analyse patterns of occurrence of disease and its association with other phenomena within a population, with a view to understanding the origins or mode of transmission of the disease.

One of the biggest disciplines of experimental science is natural science, i.e. using the scientific method (try typing that into the blog’s search box) to study nature. Examples include physics, chemistry, earth science, biology, etc. The terminology was largely introduced to distinguish them from social sciences, which use the scientific method to study human behavior. As a rule, one cannot properly teach natural sciences without laboratory components where we test almost everything that we learn.

So where do we place anthropogenic climate change in our studies? The term describes man-made changes to the physical environment and reflects on how, in turn, those changes impact humanity. Many university campuses are now affiliated with laboratory schools or demonstration schools where they train future teachers and conduct educational experimentation and research. Can we devise laboratory experiences/experiments regarding climate change on a matching scale?

Michael Bloomberg, after his three terms as mayor of NYC, started a new environmental enterprise focused on climate change. The C40 initiative currently boasts the participation of 94 cities (NYC included), which together make up 25% of the global GDP. The initiative’s latest commitment is that new buildings will conform to Net Zero Carbon by 2030 and old buildings will show net zero carbon by 2050. These are clear objectives on which one can measure progress.

The changeover to a zero-carbon environment is often expensive. Many schools, including mine, only find the necessary resources when they construct new buildings. For old buildings the conversion is even pricier (hence the delay in the target date under the C40 aspirations). Almost all the buildings in most campuses are old. Sustainable buildings and teaching laboratories each need resources for both initial costs and maintenance. We have very little experience with conversion of old buildings into more sustainable ones but we have a much richer history of working with teaching laboratories.

The initial funding for the laboratories usually comes with the original budget for the building — that is one of the main reasons that science buildings are so expensive. Once we start using it, a lab needs periodic maintenance — mainly for updating, replacing, and repairing equipment. A lot of the capital for these projects — at least at my school — comes from the students’ technology fee.

At CUNY, tuition for full-time in-state students is $3,135/semester; technology fees are $125/semester.

In 2003, the CUNY Board of Trustees adopted legislation requiring students to pay an annual technology fee. The revenues generated by the fee are to be used by the colleges to enhance opportunities for students to use current technology in their academic studies and to acquire the knowledge and skills that the modern, information-centered world requires.

Each year, a committee composed of administrators, faculty and students, chaired by the Provost, solicits suggestions from the college community and prepares a plan for the use of the technology fee funds. The plan is submitted to the Chancellor for approval. Brooklyn College’s advanced use of technology enables the committee to both pursue more advanced goals and concentrate on projects that build on mature foundations.

Approved projects are expected to further the college’s goals of: expanding student access to computing resources, improving computer-based instruction, improving support for students using college computers, improving student services, and using technology to enrich student life on campus. These goals should now [sic] only make college life more enjoyable, but also provide Brooklyn College students with an edge as they enter the job market or move on to postgraduate studies.

The committee’s plan is typically cast as a formatted spreadsheet indicating categories and examples of projects. The projects listed in the spreadsheet represent the college’s priorities, but until it is known exactly how much money will be available, the college cannot determine whether or not all of them will be funded. You can view the budget plans by clicking the links below.

My Proposal

Given NYC’s new legislation, I think it is time for CUNY to update its approach to the sustainability of its infrastructure.

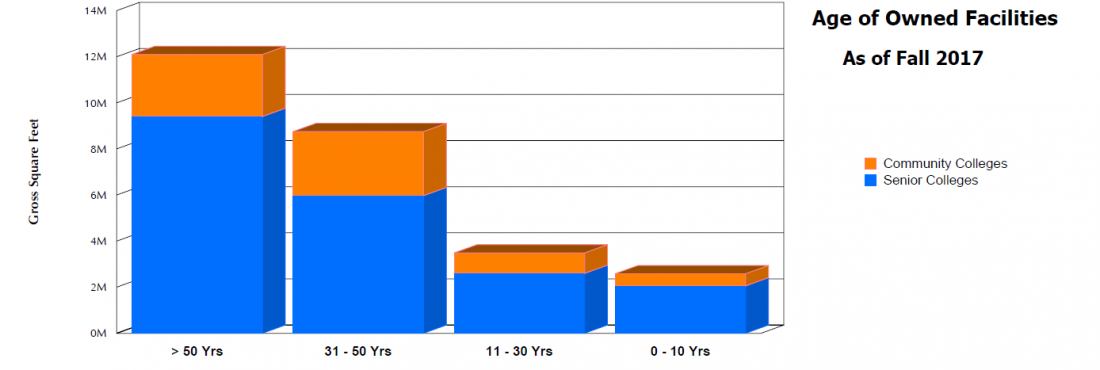

Figure 1 – Age of CUNY buildings

Figure 1 shows the age distribution of CUNY’s buildings. According to the department of energy, the average lifetime of a building made of concrete, steel, and wood is about 70 years. So, by these data, the majority of the buildings will shortly exceed their lifetimes and need to be replaced.

I propose the addition of a sustainability fee to match the technology fee, so we can start to accumulate the resources for these replacements. Majors such as Urban Sustainability and Economic Management will identify and target facilities for replacement and will collaborate with the administration in providing the technical know-how that will be required. In addition to the new fee, these projects will be funded using a mix of private donations and state budgetary allotments.

Students will issue periodic, quantitative reports about progress made in the process of converting the old buildings to zero-carbon buildings. The 20-year target difference between conversion of new and old buildings should be more than enough time for the process to be feasible.

In the next blog I will continue to add some more details about my proposed sustainability conversion.

I think adding a sustainability fee is a great idea. Students may not be in favor of paying this fee, but they have to understand that this fee and the idea of making the college and world more sustainable will come back around to benefit them as an individual in the future. It’s a small price to pay in working towards ensuring there will be a future at all.

I think initiating a sustainability fee is useful although controversial on the amount. When talking about how fast we need to react, the mere presence of the fee may influence people’s idea that indeed, NOW, is the time to react to climate change. I also feel like why all the legislation is necessary to facilitate progress, other tools like subsidies and tax expedition should be used as incentive to speed up the response and actually get businesses/municipalities moving in a green direction

While I do understand how a fee matching that of the technology fee may receive opposition, due to it adding more cost to the already costly college education students receive, it is also important to understand the importance of a sustainability fee. The reality is that funds are greatly needed to truly bring a change to the maintenance of multiple infrastructures on campus. However, I would not advocate for a sustainability fee that is equal to the technology fee. I really liked the proposal made by Fatema. Perhaps the fee could be less, not exaggeratedly lesser than the technology fee, but balanced enough to not be felt like a burden on students. From then on, students can be encouraged to seek methods of helping promote sustainability in our infrastructures.

Although I agree that imposing more fees on student may be overbearing for some, and that there may be alternative sources of funding, I think that even a very small fee per student will be enough for allocation to certain departments that specialize in dealing with urban sustainability, management, and protecting the environment. An idea that I had was that the funds could be used for aspiring environmental science major to conduct projects as part of their major requirements or as part of special programs, and that these projects can not only shed light on ways that the Brooklyn College is being wasteful, but also ways that initiatives taken on by these departments made actual differences in our campus’ carbon footprint.

I think the addition of a sustainability fee makes a lot of sense. In some ways, sustainability is more important than some of the technology that is for use in college. However, this decision might be more difficult to make for students who are not in Macaulay honors because they are already paying much more. Overall, I think the addition of a sustainability fee is a great idea and will be a great way for CUNY schools to raise money to become more efficient.