Israeli beach, May 16th

My university just wrapped up its 2020 spring semester. As in most schools, our classrooms all moved online shortly after the semester began. This shift has applied to most other activities as well. In the US we are just starting to get out and try to return to some semblance of normality.

Connecting climate change and coronavirus

The summer semester at my school will run completely online and there are very good chances that the coming fall semester will follow suit. All of us have to be prepared. I am scheduled to teach three courses next semester, all of which focus on climate change. All of my students will come into my classes having experienced the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. This blog is an important tool in my teaching and gains even more importance as I teach online. I have tried, over the last two months, to emphasize the connections between the pandemic and climate change. Both disasters stem from our interactions with our physical environment. Both are global ailments that have disastrous consequences for humankind. But they have very different time scales.

The viral pandemic rose in a matter of days and has taken weeks and months to begin its decline. Climate change, on the other hand, has risen over several generations and may not ever reach a peak. We can immediately see the consequences of the pandemic but many refuse to recognize those of climate change. As I mentioned last week, both phenomena are explicitly contagious. In the case of the pandemic, the agent of contagion is the virus. In climate change, the spread comes from the heat that we produce via our changes—both direct and indirect—to the chemistry of the atmosphere. All of this is somewhat theoretical but the two disasters certainly interact with each other.

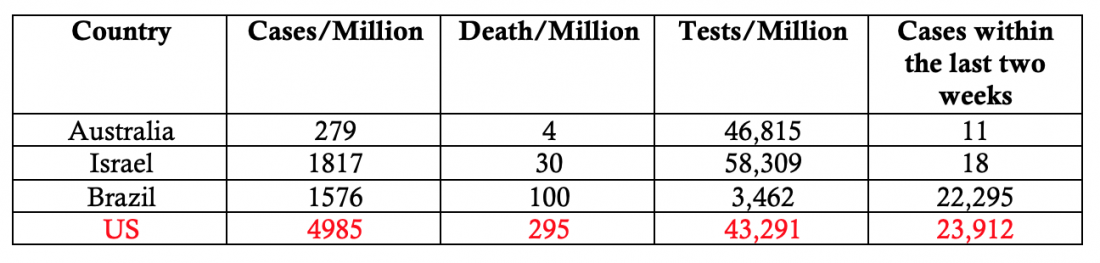

Today I wish to look at how COVID-19 has impacted four countries:

Present status of the impact of COVID-19 on four countries (as of May 23rd)

The opening picture of this blog shows a happy, boisterous beach scene in Israel. But these days the emotion it provokes in viewers may be more of trepidation than anticipation. The photograph was taken in Israel on Saturday, May 16th, in the middle of a week- long heat wave with temperatures ranging between 40-50oC (104-122oF) throughout the country. This was the most extreme mid-spring heat wave to strike Israel for at least ten years. The same heat wave struck the entire Middle East, with peak temperatures that reached 55oC (131oF) in some Gulf states.

These temperatures are much higher than the boundary of extreme danger where heat and/or sun stroke become highly likely (see the July 3, 2018 blog titled, “Heat Wave”). Israel has had one of the most successful lockdowns against the pandemic. The heat wave came only a few days after Israeli society started to reopen. The people above are trying to fight the heat wave the best way they can think of. As you can see, however, beachgoers completely broke all social distancing protocols. Many Israelis are now fearful of a second wave of the pandemic.

Australia

Meanwhile, we have Australia, where I have some family. My wife and I travel there as often as we can and I have frequently written about climate change impacts there (most recently on November 26, 2019). Nearly everyone that I know was critical of the government for its handling of the recent fires. The extreme fires seem to be growing almost every summer. Australia is very sensitive to climate change and the fires are one of the most important (and visible) consequences of this vulnerability. The country’s current government is in full agreement with our own president in denying climate change and refusing to actively attempt to decrease its impacts.

Yet, in terms of fighting the coronavirus, the same Australian government has been one of the most effective. The data in the table above show the numbers. The New York Times printed an interesting article about the government’s transition:

Did the Coronavirus Kill Ideology in Australia?

HOBART, Australia — Until four months ago few leaders seemed more influenced — even inspired — by President Trump’s worldview than Australia’s prime minister, Scott Morrison.

Mr. Morrison’s government was climate-denying, globalism-bashing and displayed an increasingly authoritarian bent. His rhetoric, even if it lacked the sriracha of Trumpetry, riffed on Trumpian themes.

As of Monday morning, Australia, with its 25.5 million people, had recorded a total of 7,054 infections and 99 deaths, according to Worldometers. That’s 277 infections and four deaths for every million people. In the United States, the per capita figures were 4,619 infections and 275 deaths per million by Monday; in Britain, 3,592 infections and 511 deaths per million.

Scientists, whom Mr. Morrison’s party has derided for over a decade, were respectfully asked for their views about the novel coronavirus and, more remarkable still, these views were acted on and amplified. Mr. Morrison dismissed the idea of trying to build herd immunity among the population, calling it a “death sentence.”

A national cabinet was formed in which the states’ premiers (the equivalent of governors) from both the left and the right regularly met by video to plot the course of the nation through the crisis. In this way and others, a government that has been sectarian and divisive became inclusive.

The economic response was as extraordinary. Civil servants who had been told they existed to serve politics and politicians also found their expert advice heeded. A huge relief package of direct fiscal stimulus was rolled out, amounting to 10.6 percent of the country’s gross domestic product — second only in the world to Qatar’s (13 percent). Unemployment benefits were doubled, a generous (though not universal) program of wage subsidy was introduced and child care was made free — all measures that only a few months ago Mr. Morrison’s party would have pilloried as dangerous socialism.

The stimulus plan was designed after negotiations with various civil society groups, including the trade unions. “There are no blue teams or red teams,” Mr. Morrison said in early April. “There are no more unions or bosses. There are just Australians now; that’s all that matters.”

He thanked Sally McManus, the first woman to head Australia’s trade union movement — a socialist and feminist, a bête noire of the right and to the left of the Labor Party mainstream, Ms. McManus is an activist who allies her politics with the likes of Bernie Sanders and Jeremy Corbyn.

It was a moment of grace, and as surreal as if Mr. Trump sought the counsel of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and then praised her.

After reading the article I couldn’t escape a certain envy: I wish that our government could show such flexibility from one disaster to the next.

Possible effects of temperature on COVID-19

So far, there has been a rather common assumption (one I shared) that COVID-19 will follow its close relatives, the influenza viruses, and disappear with rising temperatures. Nobody had any data to support or refute this assertion but China, Iran, Europe, and the US were already heavily infected while many countries in the Southern Hemisphere remained immune.

The possibility of the temperature impact was attractive because it suggested that climate change could be a force to counter such viral pandemics. However, there are still no data to support it. Indeed, Brazil now seems to be the latest hot spot in terms of the virus’ spread. The fact that its president, Jair Bolsonaro, is even worse than President Trump in his rejection of science is not much comfort. He acknowledges neither the underlying science of the virus nor that of climate change. The issue is under active research but the conditions make such work challenging. We will probably will have to wait until the end of the pandemic before we can see solid science on the matter.

Meanwhile, other climate change-amplified natural disasters continue to play out that limit people’s abilities to retain social distance. The super-cyclone Amphan struck India and Bangladesh in the middle of the lockdown, especially affecting hundreds of Rohingya refugees, who have been placed in large, crowded shelters. In the US, dams in Michigan and Virginia collapsed due to unusually heavy rain, but more than 800 people turned out to volunteer despite the pandemic. Both of these instances show the strong inter-connectivity of COVID-19 and climate change.

Stay safe.

It’s a magnificent blog and it was very informative while reading. I look forward to reading more of your blogs