Last week, I outlined some markers of how the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted the global energy transition and how that ties in with climate change in the long run. For instance, the global decrease in GDP and the resulting drop in energy use have led to a temporary reduction in global carbon emissions. Even though we are using more electricity while stuck at home, our businesses and services are using less electricity due to lockdown protocols. This may become more permanent as our society reshapes in the wake of the pandemic.

What I didn’t cover last week is the emergence of a relatively new term in the global energy vocabulary that might also stay with us after the pandemic decays: negative energy pricing.

The meaning of the term is simple: the producer of the energy pays the user, instead of the more common scenario where users pay for energy. The need for this action has the potential to create major disruptions in the energy transition.

Keep in mind that in this context, to “produce” means to convert energy from a less accessible form such as crude oil in the ground to a more useful form such as gasoline in your car. You cannot produce energy from nothing. That would violate one of the central laws of physics: the law of conservation of energy.

Ok, back to negative energy pricing. Why should the producer pay us to use the more convenient energy that cost him money to convert? In short, because there have been major disruptions to the producer’s supply and demand assumptions.

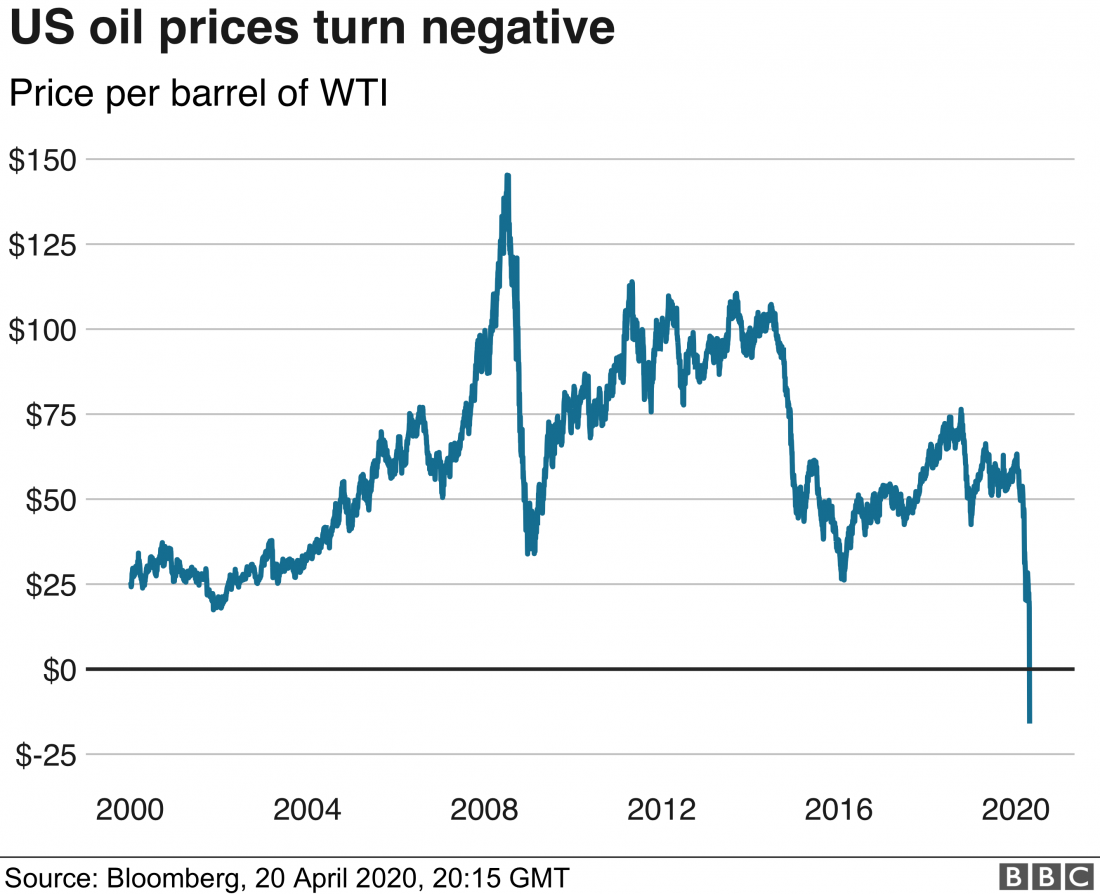

I have mentioned changes in oil prices pretty often on this blog (see July 14, 2015 and/or type oil prices in the search box). Figure 1, compiled on April 20, 2020, shows a striking drop. Up to the start of the pandemic at the end of January 2020, we see the normal fluctuations driven by changes in supply and demand and various countries’ interest. As in all capitalist enterprises, the goal is to market the product at the highest possible price.

Figure 1 – Price of West Texas Oil (Brent Crude), as of April 20, 2020

Shortly after the pandemic started, we saw a free-fall in prices. On April 20th, the value reached around -$50/barrel. That meant that if you wanted to buy the oil, you could get it for free, along with an extra $50. The main reason for such generosity was that at the time, the producers couldn’t (or didn’t want to) stop drilling—but they had no customers who wanted to buy the oil and had run out of places to store it. So, they resorted to paying people to take it. Today, the price of oil is hovering around $40/barrel. We are starting to notice some increase in economic activity and many of the producers agreed to decrease production.

Similar dynamics apply to electricity use. Below are some paragraphs from a May 22nd piece in The New York Times:

Reduced Demand for Electricity Leads to Power Giveaways

The pandemic is turning energy markets upside-down. Some consumers will get paid for using electricity.

by Stanley Reed

The coronavirus pandemic has played havoc with energy markets. Last month, the price of benchmark American crude oil fell below zero as the economy shut down and demand plunged.

And now a British utility this weekend will actually pay some of its residential consumers to use electricity — to plug in the appliances, and run them full blast.

So-called negative electricity prices usually show up in wholesale power markets, when a big electricity user like a factory or a water treatment plant is paid to consume more power. Having too much power on the line could lead to damaged equipment or even blackouts.

Negative prices were once relatively rare, but during the pandemic have suddenly become almost routine in Britain, Germany and other European countries.

With Britain in lockdown since March 23 and offices and factories closed, demand for electricity fell by around 15 percent in April, while at the same time wind farms, solar panels, nuclear plants and other generating sources continued to churn out power.

In recent weeks, renewable energy sources like wind and solar have played an increasingly large role in the European power system both because of enormous investments in these installations and because of favorable weather conditions. At the same time, the burning of coal, the dirtiest fossil fuel, has slipped. Britain, for instance, has not consumed any coal for power generation for weeks.

Such a critical shuttering of the balance between supply and demand is not restricted to major global disasters like COVID-19. The energy transition from fossil fuels to more sustainable energy sources can be an instigator on its own. Below is an example from Germany from December 2017:

Power Prices Go Negative in Germany, a Positive for Energy Users

by Stanley Reed

Germany has spent $200 billion over the past two decades to promote cleaner sources of electricity. That enormous investment is now having an unexpected impact — consumers are now actually paid to use power on occasion, as was the case over the weekend.

Power prices plunged below zero for much of Sunday and the early hours of Christmas Day on the EPEX Spot, a large European power trading exchange, the result of low demand, unseasonably warm weather and strong breezes that provided an abundance of wind power on the grid.

Such “negative prices” are not the norm in Germany, but they are far from rare, thanks to the country’s effort to encourage investment in greener forms of power generation. Prices for electricity in Germany have dipped below zero — meaning customers are being paid to consume power — more than 100 times this year alone, according to EPEX Spot.

I discussed the energy transition in Germany after my visit there last summer (October 1, 2019). At the time, I was not aware of the associated negative pricing. Such pricing always has a short duration, lasting only until the energy market learns to adjust its supply to sudden changes in demand. With sustainable energy sources in the form of wind and/or solar panels, it is a bit more challenging to address oversupply than it is with oil drilling because most of the expenses come during the installation stage. Once the systems are installed, the supply is weather-dependent and basically cost-free. But you can’t exactly reduce production. Excess electricity storage with hydroelectric facilities and/or batteries are almost never constructed to accommodate sudden changes in demand. Probably the only economically feasible way to achieve balance is through agreements with power companies that can cross state lines. Europe, the US, and other countries are pursuing such options. We all benefit from better distribution of abundant supply.