A short entry appeared in the Scientific American journal in the middle of the COP26 meeting: “Doing the Math on Biden’s Climate Pledge.” The author was trying to explain how the Biden administration—only three months after assuming control from an administration that basically refused to recognize climate change as a threat—had already made a hefty new emissions commitment, promising to reduce US CO2 emissions by 50%, compared to 2005 levels. To a large degree, the commitment was based on computer simulations by the Rhodium Group:

The Rhodium Group released a report last month that attempted to show how the U.S. could reach Biden’s 2030 target (Climatewire, Oct. 19). It assumed Congress passed a climate spending bill that lacked both the CEPP—which is out of the bill—and a fee on methane emissions from energy production—which, for the moment, is still in the bill.

“We haven’t modeled the announced package on its own, but from what we know so far, yes, it’s roughly in line with what we modeled for congressional action in our ’Pathways to Paris’ report,” said Maggie Young, a spokeswoman for Rhodium. “So, if this were to pass, along with the subsequent executive branch and subnational actions that we modeled in the report, this combination of actions would likely put the 2030 target within reach.”

But to get there, Rhodium assumed EPA and other agencies would create a host of rules for sectors that have yet to be regulated for greenhouse gases, from chemical factories to liquefied natural gas terminals to petroleum refineries.

It also envisioned muscular rules for sectors that have been regulated for carbon—like power plants—that would leave Obama-era regulations in the dust and test the boundaries of legal defensibility.

For example, the Obama-era rule for new power plants—which is still on the books—mandates that coal-fired power plants capture 40 percent of their emissions via carbon capture and storage. That requirement would be replaced with a 90 percent CCS mandate for new coal- and gas-fired power plants in a rule that would take effect next year, under the Rhodium analysis.

For existing power plants, Rhodium sees an 80 percent CCS mandate phased in for coal- and gas-fired units by 2030.

The Rhodium Group analysis was obviously not the only source of data analyzed for the commitment. Within days of the commitment’s announcement, the NYT and WSJ (among others) provided additional sources.

One important thing to consider is that the commitment ties into this administration’s goal to reclaim America’s leadership in confronting climate change among developed countries.

However, less than two weeks before the start of the COP26 meeting, the Rhodium Group issued a detailed, 35-page report on how the US can fulfill this ambitious commitment. Since the previous two blogs focused on where the commitment stands now, I thought that it would be worthwhile to use pieces of the report to summarize some of the Rhodium Group’s insights.

According to the report:

Rhodium Group is an independent research provider combining economic data and policy insight to analyze global trends. Rhodium’s Energy & Climate team analyzes the market impact of energy and climate policy and the economic risks of global climate change. This interdisciplinary group of policy experts, economic analysts, energy modelers, data engineers, and climate scientists supports decision-makers in the public, financial services, corporate, philanthropic, and nonprofit sectors. More information is available at www.rhg.com.

The Executive Summary seems rather long in comparison to the rest but it is important enough that I am duplicating most of it below with the hope that it will convince some of you to read the full report:

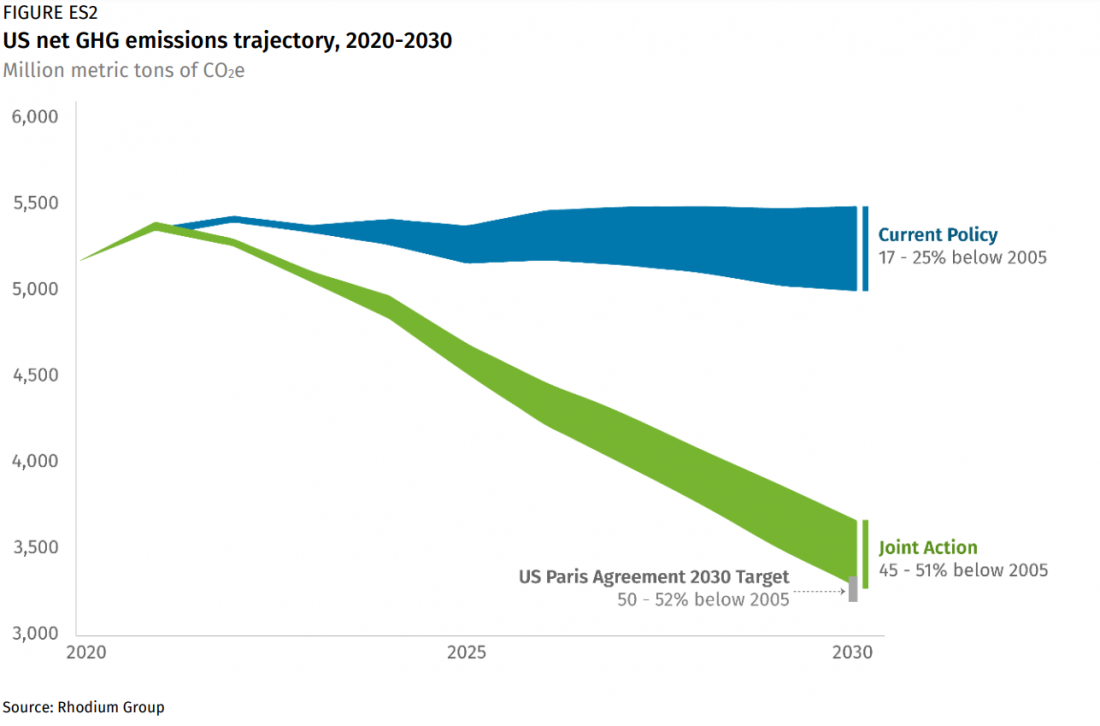

Figure 1, from the Executive Summary of the Rhodium Group report

Without new action, the US will not meet its 2030 target

Under current policy as of May 2021, with no new action, the US is on track to reduce GHG emissions 17- 25% below 2005 levels in 2030. The range reflects uncertainty around energy markets, clean technology costs and the ability of natural systems to remove carbon from the atmosphere. This leaves a gap of 1.7-2.3 billion metric tons of emission reductions required to achieve the US target in 2030 (Figure ES1). The gap is roughly equal to all 2020 emissions from the transportation sector on the low end and all emissions from electric power and agriculture combined on the high end. While the challenge of closing the gap is daunting, achieving the target is in line with what’s required to avoid the worst impacts of climate change. Not following through on this commitment risks undermining the credibility of the US and reduces the chances of an ambitious multilateral response to climate change.

Joint action by Congress, the executive branch, and subnational leaders can put the 2030 target within reach, but all must act

Our analysis demonstrates that meeting the US’s 2030 target is achievable, if Congress, the executive branch, and subnational leaders all take a series of practical and feasible policy actions—what we refer to as our “joint action” scenario (Figure ES2). This scenario represents passage this year of the infrastructure bill and budget reconciliation package in Congress, coupled with a steady stream of standards and regulations by federal agencies and accelerated action by leading states and companies. Combined, these actions can cut US net GHG emissions to 45-51% below 2005 levels in 2030.

At each level of government, we identify practical policy actions under clearly established authorities (where applicable) that, if pursued on reasonable timelines, can help achieve the target. No one level of government alone can deliver on the target. None of the policies we identify are novel or new, and all federal regulatory action can be implemented with existing legal authority. To close the emissions gap, agencies and states will need to pursue new actions at a pace, scope, and level of ambition that has not been seen to date, but which are also practical and within reach.

Action across all sectors of the economy is required to achieve the 2030 target

We find that the biggest opportunities for emission reductions in this decade reside in the electric power sector—covering 39-41% of total reductions achieved in the joint action scenario. If actions to cut electric power sector emissions are not successful, then achieving the 2030 target may not be possible. Even so, achieving the target will require successful emission reduction actions across all sectors of the US economy, not just the power sector, as well as increased natural and technological removal of carbon from the atmosphere.

Achieving the 2030 target can also cut harmful air pollutants and consumer bills

Getting US emissions on track to reach the 2030 target can be done with little cost to consumers. Long-term tax credits, investments in energy efficiency and other factors cushion consumers from price increases associated with new standards and regulations. On a national average basis, households save roughly $500 a year in energy costs in 2030 in our joint action scenario. Many policy actions that cut emissions also reduce harmful air pollutants. For example, SO2 emissions in the electric power sector decline to near zero by 2030.

If Congress fails to act, the 2030 target may be in jeopardy

Congressional action is critical to achieving the 2030 target for two reasons. First, measures in the infrastructure and budget packages can enable and accelerate clean technology deployment and on their own cut emissions significantly. Second, those same programs reduce consumer and compliance costs of federal and state actions that, combined with congressional actions, put the target within reach. Without the cost reduction assistance of congressional actions, federal and state leaders will face higher technical and political hurdles as they pursue the ambitious policies required to get to the 50-52% target. Congressional investments in emerging clean technologies will also drive innovation to enable the next wave of decarbonization after the 2030 target is reached.

Achieving the target will be a historic feat but is only halfway to the net-zero finish line

If all actors successfully pursue all aspects of the joint action scenario and achieve the 2030 target, it will represent one of the most monumental national achievements in recent decades. Even then, achieving the ambitious goal puts the nation just halfway to the longer-term goal of net-zero emissions by mid-century, which is the level required for the US to play its role in a robust global response to the threat of climate change. Getting to net-zero will require new policies and the commercial scale-up of a suite of emerging technologies like clean hydrogen, direct air capture, and advanced zero-emission electric generation, as well as continued electrification of transportation and buildings. Without near-term progress on these fronts in the years ahead, closing the gap to net-zero emissions by 2050 will be even more challenging than getting to the 2030 target.

As I mentioned in last week’s blog, we are in the middle of the story. The $1.2 trillion (new and old money) Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act was approved by Congress and signed by the president. Meanwhile, the $1.85 trillion Social Policy and Climate Change Package is still under discussion. Stay tuned.