COP26 ended with a unanimous decision on how to accelerate the global effort to mitigate climate change. This included plans to assist developing countries in their adaptation efforts and to monitor progress in these areas on an annual basis.

It’s now time to start to monitor the progress. In one of my classes, each student selected a country and has been charged to do just that. I focused on the US and how local efforts translate to global ones. This blog starts my coverage of mitigation efforts, while next week’s blog will be focused on the US and the current administration’s April 20th re-commitment to the original Paris agreement:

NATIONALLY DETERMINED CONTRIBUTION

The nationally determined contribution of the United States of America is: To achieve an economy-wide target of reducing its net greenhouse gas emissions by 50-52 percent below 2005 levels in 2030.

It took several months for the practical steps that the US was taking to fulfill this commitment to come to light. These efforts were incorporated into two resolutions drafted in collaboration with Congress and represent a summary of the present administration’s efforts to redefine the role of government in the American economy.

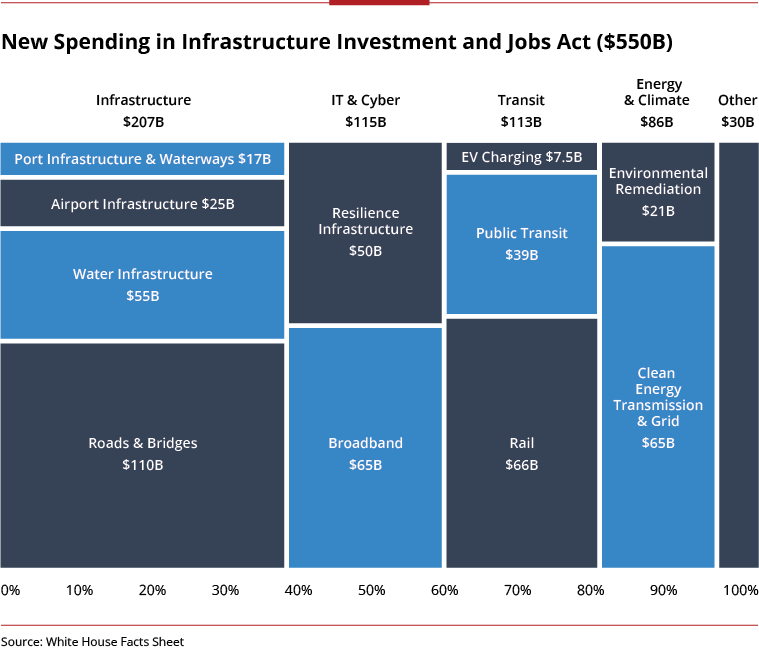

One resolution, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act was signed into law on Monday, November 15, 2021. Figure 1, from corporate services company EY, outlines the spending in that resolution. While it includes a full list of categories and their allotted budgets, it does not explicitly label climate change anywhere. However, the legislation itself features a relatively minor category addressing energy & climate, which identifies mitigation-related “key words” such as clean energy and grid—two essential concepts relating to changing our energy sources. A more in-depth examination reveals that if the executive branch of the government strongly believes in the necessity of taking a leadership position in fulfilling our COP26 commitment, most of the other categories can serve as legitimate vehicles to achieve it.

Figure 1 – Budgets for each category in the Infrastructure and Investment Jobs Act

Figure 1 – Budgets for each category in the Infrastructure and Investment Jobs Act

EY—the company that created Figure 1 using data from the White House record—wrote a description of the resolution:

Infrastructure in the Unites States is deteriorating. The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA or the Infrastructure Bill) would provide for $1.2 trillion in spending, $550 billion of which would be new federal spending to be allocated over the next five years. The historic investments included in the IIJA, from clean energy to broadband, would significantly reframe the future of infrastructure in the US.

In other words, the $550B marks the new money that has not yet been allocated through the normal budget allocation process.

Meanwhile, looking at other categories, one does not need a vivid imagination to connect improvements in public transportation with a decrease in use of private cars. As long as the majority of private cars continue to run on fossil fuels, any decrease in their use will reduce carbon emissions. This is also true for electric vehicles, unless the electricity used to charge their batteries is sourced from something other than fossil fuels.

I have explored the connections between water infrastructure and climate change multiple times (for the latest entry, see the October 26, 2021 post that deals with the Water-Energy nexus). Additionally, albeit indirectly, the category of infrastructure resilience deals with climate change: specifically, the enhanced intensity and probability of major, climate-related disasters.

As this discussion has hopefully made clear, direct calculation of how much of the infrastructure budget is allocated to addressing climate change will depend strongly on the administration that oversees that spending. By any account, even this resolution will not be enough to fulfill Mr. Biden’s pledge to halve US emissions from 2005 levels by 2030.

The largest part of President Biden’s effort to fight climate change is included in his $1.85 trillion social policy and climate change package. Below are some highlights of this package:

Climate has emerged as the single largest category in President Biden’s new framework for a huge spending bill, placing global warming at the center of his party’s domestic agenda in a way that was hard to imagine just a few years ago.

As the bill was pared down from $3.5 trillion to $1.85 trillion, paid family leave, free community college, lower prescription drugs for seniors and other Democratic priorities were dropped — casualties of negotiations between progressives and moderates in the party. But $555 billion in climate programs remained.

It was unclear on Thursday if all Democrats will support the package, which will be necessary if it is to pass without Republican support in a closely divided Congress. Progressive Democrats in the House and two pivotal moderates in the Senate, Joe Manchin III of West Virginia and Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona, did not explicitly endorse the president’s framework. But Mr. Biden expressed confidence that a deal was in sight.

The centerpiece of the climate spending is $300 billion in tax incentives for producers and purchasers of wind, solar and nuclear power, inducements intended to speed up a transition away from oil, gas and coal. Buyers of electric vehicles would also benefit, receiving up to $12,500 in tax credits — depending on what portion of the vehicle parts were made in America.

The rest would be distributed among a mix of programs, including money to construct charging stations for electric vehicles and update the electric grid to make it more conducive to transmitting wind and solar power, and money to promote climate-friendly farming and forestry programs.

This package recently passed the House but its fortune in the US Senate is still unknown. The big question remains, who is going to pay for it. Below is the latest background on this issue:

WASHINGTON — President Biden’s pledge to fully pay for his $1.85 trillion social policy and climate spending package depends in large part on having a beefed-up Internal Revenue Service crack down on tax evaders, which the White House says will raise hundreds of billions of dollars in revenue.

But the director of the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office said on Monday that the I.R.S. proposal would yield far less than what the White House was counting on to help pay for its bill — about $120 billion over a decade versus the $400 billion that the administration is counting on.

It is obvious that the Congressional Budget Office, which evaluated the bill, didn’t factor in the physical or fiscal damages that will result from a failure to mitigate and adapt to uncontrolled climate change (see blogs dated November 21, 2017, September 15, 2020, January 21, 2020).

Stay tuned. Next week, I will explore the calculations that the US administration made public that led to the April 20, 2021 commitments.