Figure 1– Shenzhen Mudslide

Figure 1– Shenzhen Mudslide

New Year’s Eve is around the corner, which makes this a great time to reflect on the last three months and follow up on my Fall Assessment (September 22, 2015). As far as global focus on climate change is concerned, the uncontested central event was the COP21 meeting in Paris and its aftermath. The conference ended with a unanimous agreement between close to 195 states regarding some of the next steps that have a decent chance of success in confronting the perils of climate change.

This recent high concentration of events has emphasized for me that anthropogenic climate change is just one aspect of a much larger issue – in fact, our whole current geological period (the Anthropocene) is dominated and determined by humans (see my February 3, 2015 blog). I have routinely given a quick exercise to my general education class where I have asked them to calculate some business as usual scenarios such as growth in GDP, population growth, and growth of greenhouse gas emissions from first principles. In all of the cases, we quickly ran into absurdities when we looked a mere few hundred years into the future – beyond my definition of “Now” (the lifespan of my grandchildren) but far short of our sense of human history and human survival. The only alternative that I can see is to develop the conditions for survival without growth.

I am going to spend the first two weeks of January 2016 visiting Cuba with some demographer friends, who will hopefully help me to quantify how we as a species (and society) might go about living without growth. I will submit some of the results of this work to professional publications, but almost all of it will find its way into this blog.

In the meantime, as usual, things happen outside of the realm of my planned set of blogs. On Sunday, December 20, a giant mudslide, filled with construction debris, hit dozens of buildings in Shenzhen, China. The number of casualties has yet to be determined. Original estimates listed 100 people still unaccounted for. By the time that I am writing this blog the estimate has been reduced to 75. Some of those people showed up, some were rescued, and some were identified post-mortem. The press framed this disaster as another example of the unintended consequences of China’s fast growth. I see it somewhat differently.

Shenzhen’s mudslide can be viewed (at least in my distorted mind) as the sad exclamation point to COP21. It conveys the urgency of the need to mitigate potential collateral damage that directly results from our urge for fast development that is designed to improve our collective standard of living. I regard it as a model for the global anthropogenic disaster that is already playing out on a global scale but is mostly visible on a local scale. In this context, it is free of the uncertainties that accompany discussions of future impact of climate change. It is also free of the NIMBY idea that motivates so many to refuse mitigation activities under the belief that if the effect is global they can rely on the actions of others to take care of the problem. In addition, since it is a concrete example, based in the here and now, it needs immediate action. That avoids the usual economic discussions of how to balance the costs of future mitigations with current efforts in such a way as to prevent the assumption that future generations will be able to pick up all the slack.

Both the greenhouse gas emissions (particularly those related to energy generation) and the mountain of building debris in Shenzhen are directly connected with efforts of economic development. In both cases sustainable alternatives to present practices need to be implemented immediately; otherwise, as science clearly predicts, business as usual practices will result in disaster. The Abelian Sandpile Model is a physics model that helps describe the instability of the Shenzhen waste mountain. The sandpile model and climate change modeling both predict tipping points in the instability that comes from continuous piling. In both cases, there have been repeated warnings about the inevitability and collective impact of these tipping points. These notices have come at a time when effective mitigation is still possible. COP21 was a key step in that direction for climate change; hopefully, the Shenzhen disaster will change waste disposal practices in other cities.

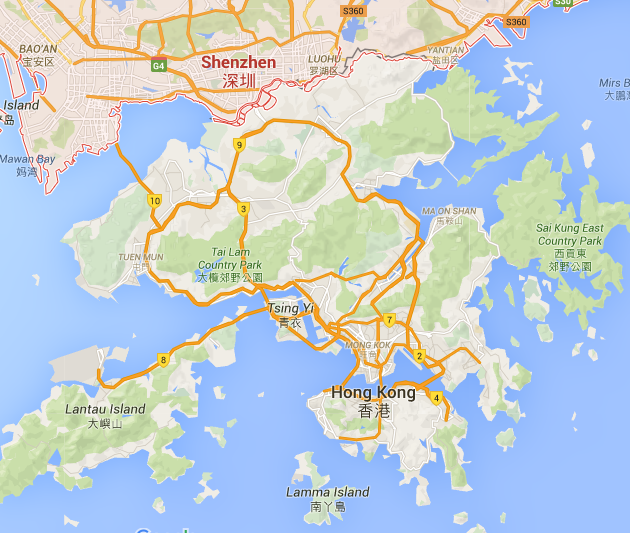

Shenzhen, which borders on Hong Kong, is the focal point of China’s recent development.  Figure 2 – Shenzhen and Hong Kong (Google maps)

Figure 2 – Shenzhen and Hong Kong (Google maps)

Shenzhen was the first, and probably the most successful of China’s Special Economic Zones (SEZs). Its SEZ status was designated in 1979. Prior to that, it was a small, dormant, market town adjacent to the then City-State of Hong Kong (now a part of China) that was (and still is) one of the most economically vibrant places on Earth. Now Shenzhen’s metropolitan area is home to 18 million people, with a 2014 GDP growth of close to 9% – considerably faster than that of China (or Hong Kong). The economics of Shenzhen have become tightly integrated with those of Hong Kong and many of the citizens of Shenzhen commute daily to jobs in Hong Kong. As in other Chinese megacities, the construction industry is trying hard to catch up and provide living accommodations for the people that are responsible for this economic boom. Planning, environmental impact and safety considerations are taking a back seat.

I will come out with a bit more cheerful news immediately after New Year’s.

Assessment: Since the end of September, on Twitter, I’m up to 348 followers. I also had 14 mentions, 32 retweets and over 62K organic tweet impressions. This is all readily accessible information. On Facebook, in the same time period, my page got an additional 12.7K impressions from 9.6K users.

On my blog itself I’m happy to report that I’ve had had 450 visits from 278 unique computers. To those of you reading, I thank you and (as always) welcome your comments.

Stay tuned. Happy New Year!