We have been seeing a slew of catastrophes throughout the world that roughly coincided with the beginning of summer in the Northern Hemisphere (June 20th). Almost all of them have been either partially caused or worsened by climate change. These disasters include record temperatures (Death Valley, California reached an alarming 130oF!), which have led to uncontrollable fires on the West Coast, whose resulting smog has impacted the entire country. Meanwhile, Arizona, Western Europe, China, and India have also experienced deadly floods. I follow the NYT Weather Report daily, tracking the temperatures and precipitation rates in many of the world’s largest cities (see my August 18, 2020 blog). Las Vegas, in particular, has stood out. I can’t remember a single day since the beginning of the summer when the city, which has a population of around 670,000, has had a high under three digits. In fact, it often exceeds 110oF. Even at night, its low temperature is almost always the highest in the US list, exceeding 85oF. Other cities on this list, such as Phoenix and Tucson, Arizona; Boise, Idaho; Salt Lake City, Utah; and Reno, Nevada have mirrored Las Vegas’ record heat. At times this summer, cities throughout the West Coast of the US and western Canada—including, shockingly, Washington and Oregon—took the lead in scorching temperatures, as years-long droughts gave way to major wildfires. Foreign cities, such as Damascus, Baghdad, Teheran, and Riyadh, matched the American records.

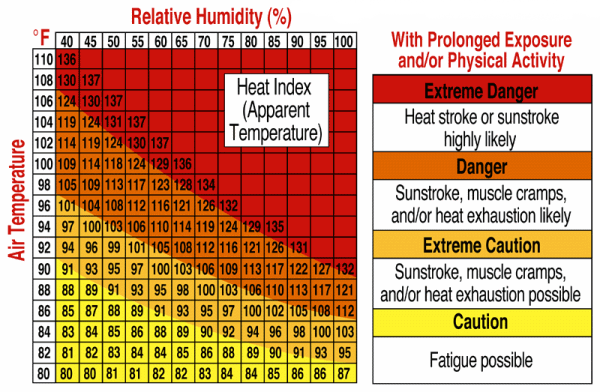

Sonya Landau, the editor of this blog, wrote a guest post from Tucson, Arizona, about some aspects of life under these conditions (June 22, 2021). She wrote that Tucson’s low humidity helps modulate the extremely high temperatures and makes life more bearable. Well, Figure 1 shows that, even with the relatively low humidity of 40%, once you reach a temperature above 100oF, the heat index reaches 110oF and you start to approach an extreme danger zone (see my July 3, 2018 blog for a more thorough explanation).

Figure 1 – Heat Index (July 3, 2018 blog)

You can alleviate the heat by running into an air-conditioned room, but, as Sonya wrote in her blog, many either have to work outside and don’t have that option or simply cannot afford air conditioning. Additionally, in many places, the electrical grid system cannot handle the extra power strain of air conditioning. As a result, many die of heatstroke. Tucson is not alone in its suffering; nor is the human race. In addition to the massive impact on the human population, heat waves have resulted in massive wildlife deaths.

Meanwhile, Bjorn Lomborg wrote a series of articles that appeared to claim that life is not so bad and that the greater decrease in cold death compensates for the increase in heat deaths. I wrote about Mr. Lomborg’s attitude to climate change and environmental issues in earlier blogs (See my September 3, 2012 blog, “Three Shades of Deniers”). For a time, I also used his most famous book, The Skeptical Environmentalist, in my climate change classes. I appreciated his skeptical input as long as it was based on facts but that connection has become increasingly shaky. He started to post about the correlations between heat deaths and cold deaths four years ago on his own website:

“Heat-death hysteria: the wrong reason to fight climate change”

2017-07-10

Politically tinged coverage of summer temperatures offers a lot of heat but not much light. “Deadly heat waves becoming more common due to climate change,” declares CNN. “Extreme heat waves will change how we live. We’re not ready,” warns TIME. Some stories are more sensationalist than others, but there is a common theme: Dangerous heat waves will increase in frequency and ferocity because of global warming. This isn’t fake news. In fact, it’s perfectly true. But these stories reveal a peculiar blind spot in the media’s climate reporting. While “deadly,” “killer,” “extreme” heat waves gain a lot of coverage, relatively scant attention is given in winter to much, much more lethal cold temperatures.

He repeated the same arguments over the years in other publications:

New York Post — “More people die of cold: Media’s heat-death climate obsession leads to lousy fixes”

USA Today — “Climate Change: science, media spread fears, ignore possible positives”

This month, he expanded upon this point:

A widely reported recent study found that higher temperatures are now responsible for about 100,000 of those heat deaths. But the study’s authors ignored cold deaths. A landmark study in Lancet shows that across every region climate change has brought a greater reduction in cold deaths over the past few decades than it has caused additional heat deaths. On average, it has avoided upwards of twice as many deaths, resulting in perhaps 200,000 fewer cold deaths each year.

These entries all refer to “recent studies,” which entail a single 2015 publication in The Lancet. Below is a summary of the methodology and findings of that paper:

Methods

We collected data for 384 locations in Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, Italy, Japan, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, Taiwan, Thailand, UK, and USA. We fitted a standard time-series Poisson model for each location, controlling for trends and day of the week. We estimated temperature–mortality associations with a distributed lag non-linear model with 21 days of lag, and then pooled them in a multivariate metaregression that included country indicators and temperature average and range. We calculated attributable deaths for heat and cold, defined as temperatures above and below the optimum temperature, which corresponded to the point of minimum mortality, and for moderate and extreme temperatures, defined using cutoffs at the 2·5th and 97·5th temperature percentiles.

Findings

We analysed 74 225 200 deaths in various periods between 1985 and 2012. In total, 7·71% (95% empirical CI 7·43–7·91) of mortality was attributable to non-optimum temperature in the selected countries within the study period, with substantial differences between countries, ranging from 3·37% (3·06 to 3·63) in Thailand to 11·00% (9·29 to 12·47) in China. The temperature percentile of minimum mortality varied from roughly the 60th percentile in tropical areas to about the 80–90th percentile in temperate regions. More temperature-attributable deaths were caused by cold (7·29%, 7·02–7·49) than by heat (0·42%, 0·39–0·44). Extreme cold and hot temperatures were responsible for 0·86% (0·84–0·87) of total mortality.

Ten other scientists analyzed Lomberg’s findings, concluding that its scientific credibility was ‘low’ to ‘very low’:

SUMMARY

On 4 April 2016 the US Global Change Research Program released a comprehensive overview of the impact of climate change on American public health. In an op-ed in the Wall Street Journal, Bjorn Lomborg criticizes the report as unbalanced. Ten scientists analyzed the article and found that Lomborg had reached his conclusions through cherry-picking from a small subset of the evidence, misrepresenting the results of existing studies, and relying on flawed reasoning.

Below are the opinions of two of the reviewers cited in this publication. One of these, who was a co-author of the original Lancet report, claims that Lomborg’s interpretation of the report is misleading. The other reviewer says that Lomborg is falsely conflating heat and cold deaths with seasonal variations of summer and winter:

Antonio Gasparrini, Senior Lecturer, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine:

My review is limited to the part of the article that describes the results of the study published in The Lancet, which I first-authored.

The interpretation provided in the article is misleading, as our study is meant to provide evidfence on past/current relationships between temperature and health, and not to assess changes in the future. In addition, the study does not offer a global assessment, and it is limited to a set of countries not representative of the global population.

Kristie Ebi, Professor, University of Washington:

Mr. Lomborg is confusing seasonal mortality with temperature-related mortality. It is true that mortality is higher during winter than summer. However, it does not follow that winter mortality is temperature-dependent (which summer mortality is). Dave Mills and I reviewed the evidence and concluded that only a small proportion of winter mortality is likely associated with temperature. A growing numbers of publications are exploring associations between weather and winter mortality, with differences in methods and results. The country with the strongest association between winter mortality and temperature is England, which appears in other publications to be at least partly due to cold housing. Winter mortality is lower in northern European countries.

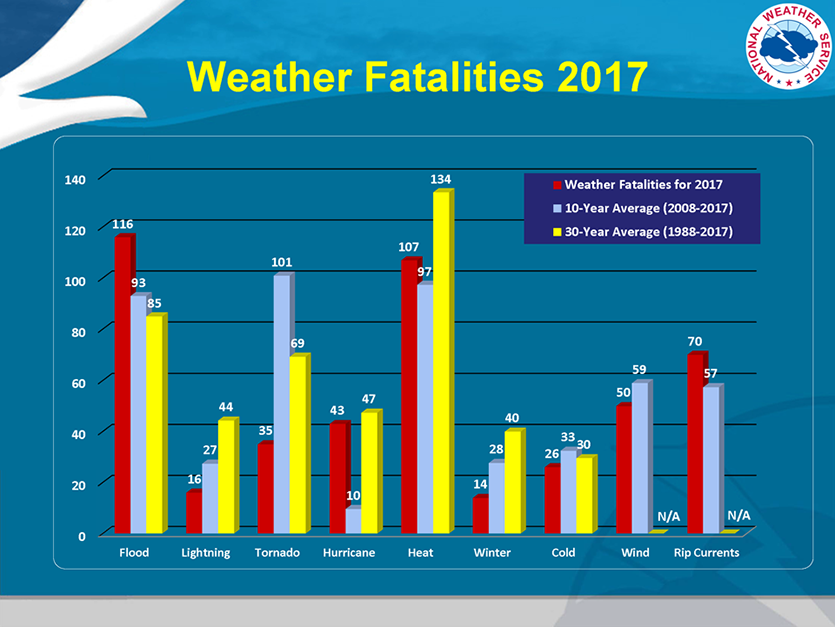

As always, there is a grain of truth in Lomborg’s argument. Below is a statistical evaluation of weather fatalities in 2017, compiled by NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) and published by Weather Underground:

Figure 2 – Weather fatalities: Weather-related deaths in the U.S. in 2017 (red bars), for the past 10 years (blue bars), and for the last 30 years (yellow bars), According to NOAA. Heat-related deaths dominate.

Extreme heat and extreme cold both kill hundreds of people each year in the U.S., but determining a death toll for each is a process subject to large errors. In fact, two major U.S. government agencies that track heat and cold deaths–NOAA and the CDC–differ sharply in their answer to the question of which is the bigger killer. One reasonable take on the literature is that extreme heat and extreme cold are both likely responsible for at least 1300 deaths per year in the U.S. In cities containing 1/3 of the U.S. population, a warming climate is expected to increase the number of extreme temperature deaths by 3900 – 9300 per year by 2090, at a cost of $60 – $140 billion per year. However, acclimatization or other adaptation efforts, such as increased use of air conditioning, may cut these numbers by more than one-half.

NOAA’s take: heat is the bigger killer

NOAA’s official source of weather-related deaths, a monthly publication called Storm Data, is heavily skewed toward heat-related deaths. Over the 30-year period 1988 – 2017, NOAA classified an average of 134 deaths per year as being heat-related, and just 30 per year as cold-related—a more than a factor of four difference. According to a 2005 paper in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, Heat Mortality Versus Cold Mortality: A Study of Conflicting Databases in the United States, Storm Data is often based on media reports, and tends to be biased towards media/public awareness of an event.

CDC’s take: cold is the bigger killer

In contrast, the CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics Compressed Mortality Database, which is based on death certificates, indicates the reverse—about twice as many people die of “excessive cold” conditions in a given year than of “excessive heat.” According to a 2014 study by the CDC, approximately 1,300 deaths per year from 2006 to 2010 were coded as resulting from extreme cold exposure, and 670 deaths per year from extreme heat. However, both of these numbers are likely to be underestimated. According to the 2016 study, The Impacts of Climate Change on Human Health in the United States, “It is generally accepted that direct attribution underestimates the number of people who die from temperature extremes.” For example, during the 1995 Chicago heat wave, only 465 death certificates had heat as a contributing cause, while excess mortality figures showed that close to 700 people died as a result of the heat

I will further explore this issue in next week’s blog. It seems that a great part of this discussion is a matter of language and clarifying certain terms. As the second reviewer of Lomborg’s paper pointed out, many of The Lancet and Lomborg’s discussions are based on the association of cold with winter and heat with summer.

Figure 2 lists many causes of death, including floods, tornados, and hurricanes, which are triggered or amplified by the extreme heat caused by climate change. However, it doesn’t even mention death by fire, making it much harder to compare with earlier data:

Between 1998 and 1999, the World Health Organization revised the international codes used to classify causes of death. As a result, data from earlier than 1999 cannot easily be compared with data from 1999 and later.

Unsurprisingly, many mentions of extreme heat in the news are accompanied by warnings that worse is yet to come. Newsrooms around the world are paying special attention to any new local temperature records. In the next blog, I will go into some quantitative detail about the impact extreme heat has on all of us.

Stay tuned.

As with most statistical methods, the Lancet study shows correlation but not necessarily causation. That is the variation of excess deaths, particularly associated for mild hot or cold conditions may actually be more directly related to other factors that are also related to seasonal patterns of temperature. For example, seasonal variations of temperature affects human behavior, such as time spent either outside or inside, and it may be that such correlations of behavior and temperature confound the study findings. It should also be noted that the study is based on outside temperatures and that in developed countries in temperate climates, most people spend most of their time in heated or cooled indoor environments. These confounding factors do not appear to be adequately addressed by the study, leading some naive readers to overly broad conclusions in support of or denial of preconceived climate change impacts.

“Well, Figure 1 shows that, even with the relatively low humidity of 40%….”

The yearly average RH is Tucson is 29%

http://www.tucson.climatemps.com/humidity.php

“From 2000–03 to 2016–19, the global cold-related excess death ratio changed by −0·51 percentage points (95% eCI −0·61 to −0·42) and the global heat-related excess death ratio increased by 0·21 percentage points (0·13–0·31), leading to a net reduction in the overall ratio.”

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanplh/article/PIIS2542-5196(21)00081-4/fulltext