I have been (starting on September 21st) focusing on energy companies’ transitions away from fossil fuels; many are finally realizing that such global shifts are necessary if we cannot implement an acceptable way to capture the immense amounts of carbon we emit. While the energy companies are the sector with the most potential for change, the related climate catastrophes affect us all.

In September of this year, Rex Tillerson, the former CEO of ExxonMobil, questioned, “what good is it to save the planet if humanity suffers?” (September 21, 2021). In a certain sense, he is right—that is, if humanity suffers in the transition to save the planet, chances are that people will not be willing to go along with the necessary changes. A “return to the cave”—or less technological—scenario is not an option. Of course, in order to avoid inflicting mass misery, such a global transition will necessarily be both complex and time-consuming. It must replace fossil fuels with sustainable energy—or at least, energy alternatives that don’t end up changing the chemistry of the atmosphere in a detrimental way. (This will likely include nuclear energy and carbon capture). At the same time, the transition must ensure a constant supply of sufficient energy to drive the global economy while also supporting a growing human population. Since a polluted atmosphere is global, the energy transition must be global as well to include both mitigation and adaptation to the new climate. Arguments such as “Make America Great Again” (MAGA), which focus on a specific country or region, must be replaced by new slogans such as “Keep Our Planet Livable.” Otherwise, rising social unrest will stop the transition cold, putting our collective existence in question.

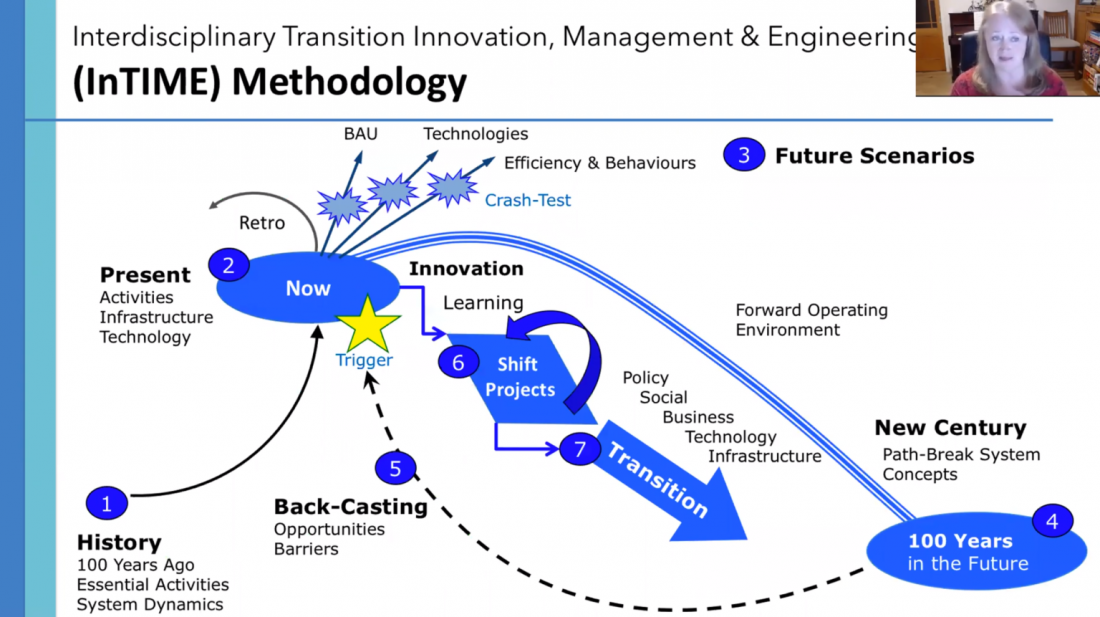

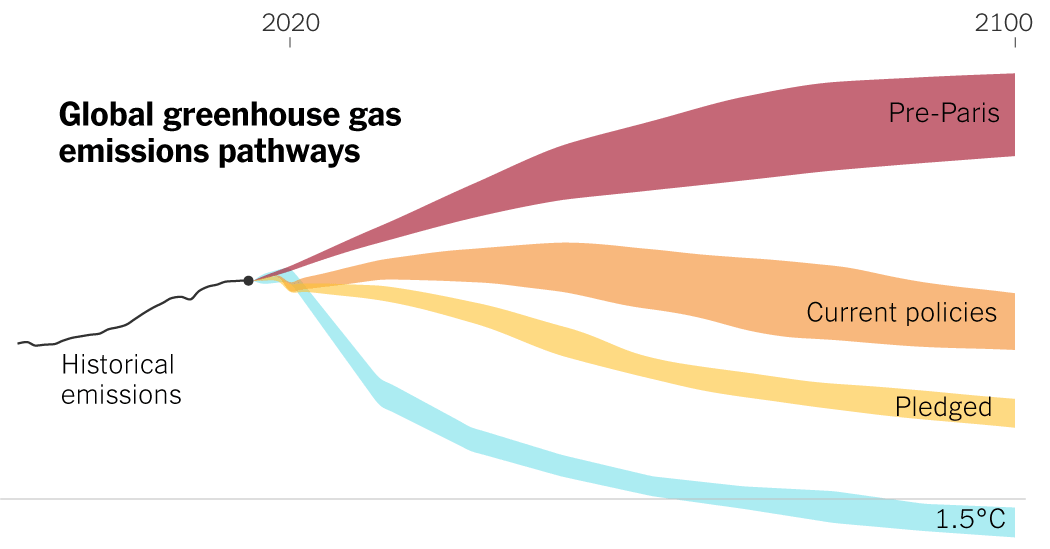

Figures 1 and 2 show the two faces of such transitions. Figure 1, taken from a CleanTechnica piece about the Global Association for Transition Engineering (GATE) shows schematics for how an engineer sees such a transition, while Figure 2, taken from the NYT article I cited above, shows how we present the transition in layman’s terms: as a one-parameter event that extrapolates the future climate based on how much carbon we emit.

Almost immediately after the opening of COP26, President Biden was caught in what seemed to be a duplicitous statement:

President Biden told a global climate summit on Monday that “we only have a brief window before us” to reduce the emissions from burning oil, gas and coal that pose an “existential threat” to humanity. But only days earlier, he was urging the world’s largest oil producers to pump more of the fossil fuels that are warming the planet.

The incongruity was on center stage both at the global climate summit currently taking place in Scotland, and in Rome this past weekend during a gathering of leaders from the 20 largest economies. The president’s comments highlighted the political and economic realities facing politicians as they grapple with climate change. And they underscored the complexity of moving away from the fossil fuels that have underpinned global economic activity since the Industrial Age.

“On the surface, it seems like an irony,” Mr. Biden said at a news conference Sunday. “But the truth of the matter is — you’ve all known; everyone knows — that the idea we’re going to be able to move to renewable energy overnight,” he said, was “just not rational.”

This does not mean that President Biden is a duplicitous man; he understands the nature of the energy transition that we are trying to enact. However, he also realizes that we are also trying to recover from the economic damage that COVID-19 has inflicted on the world—and the current global energy shortage has major impacts on that recovery:

Much of the world is suddenly worried about running short of natural gas, and the impact is being felt in surging utility bills, shuttered factories and a rising desperation as winter approaches.

Across Asia, Europe and Latin America, consumers still reeling from the pandemic are finding energy costs soaring, driven higher by natural gas prices that have increased fourfold in some regions in recent months, hitting record highs this week. Makers of chemicals, steel, ceramics and other goods that require large amounts of energy are seeing their bottom lines squeezed and, in some cases, suspending operations.

In South Korea, electric rates just increased for the first time since 2013, and small businesses that struggled under months of strict pandemic rules are now fearing future price jumps. “It’s already hard for small businesses to survive,” said the Korea Federation of Micro Enterprise.

In Brazil, the worst drought in 90 years has depleted hydroelectric output, forcing power generators to import expensive natural gas. The government raised electricity prices by nearly 7 percent in September, after a nearly 8 percent increase in July.

Europeans are also feeling the pinch. In Spain, the government recently said it would take profits away from energy companies to help rate payers. In Italy, residents were recently hit with a 14 percent increase in their gas bills, accompanied by a nearly 30 percent jump in electricity rates.

“We’ll have to do the dishes or laundry at nighttime to save money,” said Carla Forni, a teacher and mother of two in Bologna.

In China, already the world largest importer of natural gas, demand is up 13 percent as Xi Jinping, the country’s leader, presses forward with plans to clean up the environment by turning away from coal.

As a major gas exporter, the United States has been benefiting from the strong global demand. Of late, prices that have risen to their highest levels in years have prompted calls to rein in the shipments abroad. American prices, though, are just a fraction of those seen recently in Europe and Asia.

All these shortages coincide with the opening of the COP26 meeting, one of whose main agendas is to establish a timeline to stop the use of coal:

Coal was supposed to be headed to the dust bin of history as the world increasingly embraces renewable energy.

After all, many countries were shutting down these sooty, air-choking power plants. Mines closed, coal companies went bankrupt, and utilities started to replace coal-fired electricity generation with natural gas or wind and solar energy.

But it turns out that weaning the world off fossil fuels, particularly the dirtiest fuel of them all, isn’t going to be easy or quick, as coal’s price and demand have been revived this year. Transitions take time.

“From our point of view, the energy transition was always a multi-decade story,” said Biff Ourso, senior managing director, Nuveen Real Assets. “And there’s invariably going to be periods of spikes in demand, or supply/demand imbalances that was going to cause a resurgence in carbon-based generation sources.”

Coal is likely to stick around as countries rely on it to ensure the lights stay on and the economy hums along. Coal’s resurgence also shines a light on the need for improved battery storage for renewables if the world is going to decarbonize.

In spite of these energy shortages, 40 countries—among them several major coal users—signed an agreement that laid out a timeline for ending their use of coal:

In a surprise announcement from the COP26 climate summit in Scotland, an international agreement has been reached to accelerate the end of coal, the fossil fuel that is the single biggest source of the emissions that cause climate change.

According to a release from the U.K. Government’s Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS), 18 additional countries will commit to ending their use of coal in the 2030s and the 2040s. These include the highly coal-dependent nations of Poland, Vietnam, Egypt, Chile and Morocco.

Importantly, the agreement does not include the coal-heavy powers China or Russia, the first and fifth most polluting nations respectively, whose leaders are not attending the summit in Glasgow. However, in the run up to the COP, China reaffirmed its commitment to achieve net-zero carbon emissions by 2060 and to reach peak emissions by 2030.

China, as well as Japan and Korea, announced within the last year that they would no longer fund new coal-power projects overseas.

The announcement also does not cover India, though on Monday the nation’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced a series of new carbon-cutting goals, with pledges to reach net-zero carbon emissions by 2070, and to slash emissions by 1 billion tons by 2030.

Of course, as the article mentions, not all of the major coal producers or users are among the signatories. Next week, we’ll be nearing the end of COP26 meeting, and should have a clearer picture of the various commitments.

Very interesting research! Good read.