As I have mentioned in previous blogs, after three years of COVID-19 hibernation, my wife and I just came home from visiting friends and family in England, Poland, and France. I will spend a few days teaching the first week of classes, then return for a few days to Germany for a delayed celebration of the liberation of Bergen-Belsen, the concentration camp in which I spent the second half of WWII. This opportunity to visit Europe at the tail-end of summer enables me to have a look at how the continent is trying to adapt to the ever-increasing climate change that is heating it. The Russian invasion of Ukraine has accelerated the energy transition under which these efforts take place. Additionally, most European countries, and many others, are working to help Ukraine defend itself.

Within the three weeks that I spent in Europe, we had one rainy afternoon in Krakow, Poland. The rest of the time was sunny days with visible drought, especially in London. I am starting to write this blog a day after returning to New York, where heavy rain issued a warm welcome. For two days–one in London and one in Warsaw–the high temperature exceeded 90oF. Other days were hovering in the mid-80s. To a New Yorker, this doesn’t seem like a heat wave; in the places that I visited in Europe, it seemed hot mainly because of the lack of air-conditioned spaces to escape to. The hotels that we stayed in were air-conditioned. However, most days we stayed with family and friends. With one exception, none of these private residences had air-conditioning, although fans are starting to be installed. Socioeconomic conditions were not an obstacle to adaptation in the places that I visited. As we will see below, people are starting to adapt. In Paris, I used to go to the area of the Notre Dame cathedral to have my ice cream. Now, the best ice creams that I ever tested are spread across the city. The use of bikes and scooters is expanding. As we will see below, the energy transition is not yet directly hitting but fear of approaching consequences for consumers is widespread. This fear is based on estimates of the pricing of energy use. In most cases, the last estimate came out before the Russian invasion. Everybody is expecting a sharp price jump for the next estimate (see England below, which has just issued its newest estimate). All of these are by necessity limited personal observations. The rest of the blog will examine how my observations fit into more general, published observations:

One can find a good survey of the situation in some of the European countries on Business Insider:

The European energy crisis set into motion by the Russian invasion of Ukraine shows no signs of abating and looks to deepen further in coming weeks as record heatwaves hit the continent.

In France, the crisis is so bad that power stations are being permitted to break environmental rules to stay open as the country struggles to maintain national energy supplies, according to a report from Bloomberg.

The French Nuclear Safety Authority (ASN) granted a temporary waiver allowing five nuclear plants across the country to dispense more than the authorized amount of hot water into rivers, the news agency reported.

In France, rivers and waterways are used to cool power plants. Under the current environmental rules, nuclear plants must reduce or stop output when river temperatures reach a point at which use by the plants may harm the environment, per Bloomberg. That provision is being temporarily halted.

Europe’s prolonged high temperatures are putting further pressure on the bloc’s already strained energy supplies.

The River Rhine, one of the continent’s most important rivers, is drying up amid the record-breaking summer heatwaves, Insider reported last month. The river is currently at its lowest level in at least 15 years, making moving goods — including coal and gas — in container ships down the river a challenge.

Northwest and central Europe are set for even more hot weather in the coming weeks. Temperatures in the UK, France, and Germany are expected to soar on Friday, with some estimates predicting highs of 96.8 degrees Fahrenheit by the end of the week.

You can find additional coverage on ABC:

In Germany, falling water levels of the River Rhine have left it impassable to many boats.

Further south, Spain is facing its worst drought on record, with research suggesting the Iberian Peninsula could be the driest it has been for more than 1,000 years.

Its drought has also led to the emergence of a prehistoric stone circle dubbed the “Spanish Stonehenge”, which has only been fully visible four times since 1963.

Neighboring France is experiencing its worst drought since records began in 1958, its national weather agency says.

On average, less than 1cm of rain fell across France in July and scores of villages have been left to rely on deliveries from water trucks as taps run dry.

Italy’s worst drought in decades has reduced Lake Garda — the country’s largest lake — to near its lowest level ever recorded, exposing expanses of previously underwater rocks.

Water levels in many of Switzerland’s rivers and lakes have also fallen to very low levels.

The water scarcity resulting from these heat waves extends beyond Europe:

Water is a scarce commodity and has been for a long time. And often it is a contested one. A 4,500-year-old stone from Mesopotamia, in today’s Iraq, is on display in the Louvre museum in Paris. Engraved on it are scenes of battle and war the kings of Lagash and Umma fought, in part over water.

Since then, the value of water has multiplied. Eight billion people now live on earth and they all need drinking water. But above all, agriculture and industry, consume gigantic quantities of water. At the same time, climate change is upsetting the rhythm of rain and drought.

When Ethiopia builds a dam on the upper reaches of the Nile, Sudan and Egypt fear for their lifelines. The Ilisu Dam in Turkey, dams the waters of the Tigris River — which means that less water arrives in Iraq. The Euphrates River is dammed in several locations. In 2018, a study conducted on orders of the EU Commission identified eight rivers where the risk of conflict over the use of increasingly scarce water is particularly high: The Nile, Euphrates, and Tigris, as well as the Ganges, Brahmaputra, Indus, and Colorado Rivers.

Energy Costs: Britain’s latest announcement is grim

For months, a tsunami of high energy costs has borne down on Europe. On Friday, the first big waves crashed ashore in Britain, with the news that household gas and electricity bills will nearly double in October.

The announcement, by Britain’s energy regulator, raised the specter of a humanitarian crisis in one of the world’s richest countries: Millions of Britons might not be able to afford to heat or light their homes this winter, unless the government steps in on an enormous scale to cushion them from the vagaries of the market.

Here’s how the rest of Europe is currently faring:

European gas and power prices surged as panic over Russian supplies gripped markets and politicians warned citizens to brace for a tough winter ahead.

Benchmark gas settled at a record high, while German power surged to above 700 euros ($696) a megawatt-hour for the first time. Russia said it will stop its key Nord Stream gas pipeline for three days of repairs on Aug. 31, again raising concerns it won’t return after the work. Europe has been on tenterhooks about shipments through the link for weeks, with flows resuming only at very low levels after it was shut for works last month.

Adaptation: One of the first things we think about to deal with the heat is air conditioning:

Three-quarters of all homes in the United States have air conditioners. Air conditioners use about 6% of all the electricity produced in the United States, at an annual cost of about $29 billion to homeowners. As a result, roughly 117 million metric tons of carbon dioxide are released into the air each year. To learn more about air conditions, explore our Energy Saver 101 infographic on home cooling.

The energy-intensive cooling system used widely across the United States has grown increasingly attractive to Britons and other Europeans now dealing with brutal summer temperatures caused in part by human-induced climate change. In recent days, extreme heat has scorched much of Western Europe, kindling wildfires in France, Greece and Italy and causing the deaths of more than 1,000 people in Portugal alone.

Sales of portable air-conditioning units rose 2,420 percent in a week, British retailer Sainsbury’s said Monday. And a surge in demand for centralized AC units in London has some installation companies booked through the fall.

But why weren’t European households already equipped with air conditioning? And will Europe fall victim to a “U.S.-style addiction to AC,” as climate control researcher Stan Cox has warned?

Meanwhile, the EU seems to be saving energy overall:

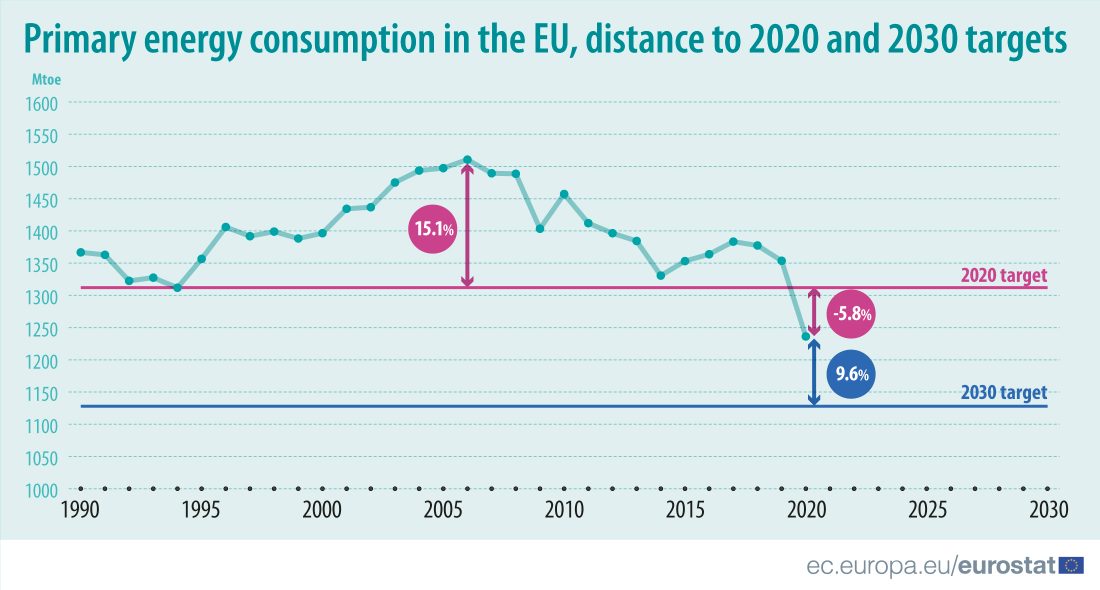

Figure 1 – Primary energy consumption in the EU (Source: Eurostat)

Most of the decrease in energy consumption shown in Figure 1 originates from the pandemic. Europe has tried to support Ukraine’s attempts to defend itself against invasion. In response, as “punishment,” Russia has disrupted its energy supply. So far, it’s too early (at least in my searches) to quantify the related impact of deliberate energy-saving efforts. Another contributor to carbon emissions is transportation:

Another contributor to carbon emissions is transportation:

If people around the world were as enthusiastic cyclers as they are in the Netherlands, we could cut an impressive amount of planet-heating pollution. The Dutch use bicycles to get around more than folks in any other country, cycling about 2.6 kilometers (1.62 miles) a day.

If that was the trend across the world, it would slash 686 million metric tons of carbon dioxide pollution a year, according to the authors of a new study published this week in the journal Communications Earth & Environment. That’s enormous — roughly equivalent to erasing one-fifth of CO2 emissions from passenger cars globally in 2015.

In the meantime, during our absence, the energy transition in the US got a big boost with the passage of the “Inflation Reduction Act.” I will return to the impact of this development after my trip to Germany.

New York is bi-coastal, which means that it goes through all 4 seasons. Summer in New York only lasts for 4 months, which means that New York has a different climate than any other star in the country.

I think that people use air conditioners as a ozone layer to prevent them from sweating too much, but at the same time, using it too much, it wastes a lot of electricity and power and it may cause them to pay so much money.

The temperature in the 80s to 90F in the summer time is a normal weather in New York.In your blog you have mentioned that different countries their temperature has a greatly change. I saw that you have been to London and the temperature there has a high increase. However, now a day more and more people has become more aware of the weathers because of the energy that’s being used these day.

Even though summer only lasts for a few months, having everyone in New York use air conditioners contaminates the ozone layer. It also reminds me of the refrigerator, which runs nonstop every day of the year until it breaks or the power goes out. Amazingly, older types of refrigerators release a lot more chlorofluorocarbons (CFC) than newer ones do. Numerous manufacturers claim, not everyone will be eager to trade in their present refrigerator for a newer one unless it’s free, assuming that the new ones don’t produce CFCs.

You’ve mentioned that the high temperatures of 90 F and mid-80s wasn’t a surprise for New Yorkers as it isn’t considered much of a heat wave, to which you’re right as I found it odd that one would think that’s overheating, but I thought that without taking into account that countries temperatures differ greatly. And how I’ve never been to London I wouldn’t personally be aware of it’s usual temperatures but from your blog it appears that London’s temperature are rising. Now from what I’ve read people are more alarmed because at the increase of energy use that’s coming because there’s not enough cooling systems and not as a form of climate change and it’s casualties. I could be wrong but this is ultimately what I’ve taken away as the main problem/concern.