Figure 1 – Past, now, and future

Figure 1 – Past, now, and future

Past:

The past tells us what has already happened. Last week’s blog addressed this through both its top figure and the speech of Camille Robcis, the new chair of Columbia University’s History Department. Prof. Robcis recommended that historians should extend their interest to include the present but never explained how she defines the present. In this blog, I will explain how I define the present and some of the methods that are being used to try to predict the future.

Present:

If I ask AI (through Google) to define the present, I get a few options. I will focus here on the most general one, given below:

Philosophical Meaning

In a philosophical context, “being present” means to be mindful and fully aware of and engaged with the current moment, rather than dwelling on the past or worrying about the future. This is the basis of the common saying, “Yesterday is history, tomorrow is a mystery, but today is a gift. That’s why they call it the present”.

Readers will notice that in AI’s philosophical definition, the present is defined not on its own terms but instead as it relates to the past and the future. This is also conveyed in the top figure. I will define present in terms of two associated words: simultaneity and now. The present was described in earlier blogs in terms of both these associated words (“simultaneity” in the October 15 and 22, 2013, and May 31, 2022 blogs, and “now” on March 9, 2021, in a blog entitled “My ‘Now‘”). The October 15, 2013, blog introduced the important concept of the light-cone and its association with special relativity. This basically claims that because of the finite speed of light, we observe any object with a slight time delay that changes with the object’s distance. The speed of light in a vacuum is approximately 300 million meters/sec or 700 million miles/hr. It changes with the medium through which the light moves. So, the time delay for observing an object 1m away will be approximately 3×10-9 sec or 3 nanoseconds. Obviously, for short distances, such a delay is negligible, but for large cosmological distances, the delay is critical.

For myself, I have defined the present based on the concept of now, in terms of interactions during my extended life span, starting with my birth and ending with the expected lifespan of my grandchildren. Following this definition, the present will be subjective for each of us. Following this definition of now, the main global threats that I have enumerated in previous blogs (See “What are we trying to teach our children,” from June 11, 2024) have taken place in my present. It should be obvious from this subjective definition of now that there is a large overlap in this kind of present with both the past and the future. This is also reflected in the opening figure of this blog.

Future:

Reality in the past (including the part of the past that overlaps our present) does not change and can be investigated. As I mentioned in earlier blogs, we are not prophets (see blogs from August 13, and 20, 2012) and we can only predict the future (including the part from our extended present) in terms of probabilities. Some of the ways that we use to estimate these probabilities, mainly in the context of climate change, are given in previous blogs:

Extrapolating from the present (February 17, 2015)

Computer simulations (February 6, 2018)

We are not prophets (August 13, 2012)

Predicting the Future and its Impacts (July 7, 2015)

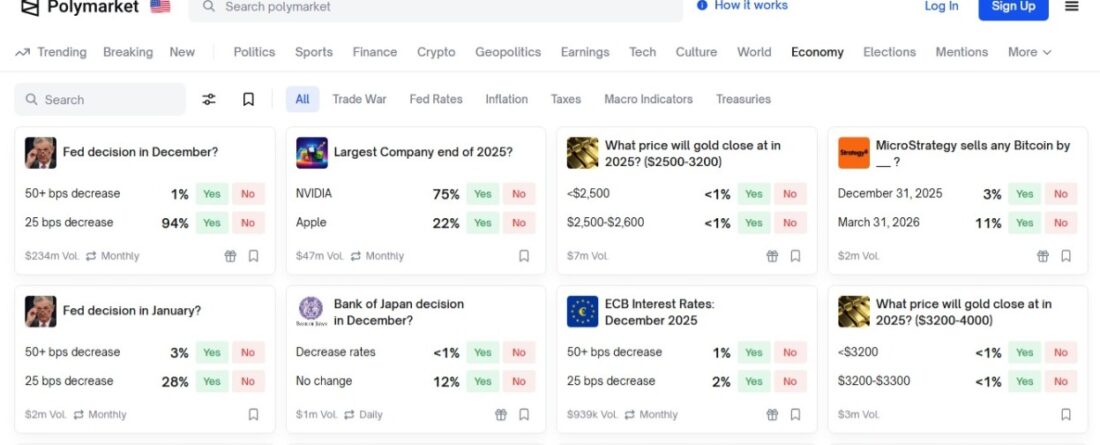

A few days ago, I was watching the CBS program, “60 minutes,” to learn more about predicting the future another way: betting. Online betting is now incredibly popular. This type of prediction mainly focuses on sports results. What I learned from “60 minutes” is that it’s now being extended to the future. Figure 2 shows part of the site of this betting platform.

Figure 2 – Economy Odds & Predictions | Polymarket

Figure 2 – Economy Odds & Predictions | Polymarket

Why do we need to know about possible futures? Despite a very low probability, the Chicxulub Event is a real example of something that actually took place. As a result, it is now part of Earth’s past:

65 million years ago an asteroid roughly 10 to 15 kilometers (6 to 9 miles) in diameter hit Earth in what is now [Chicxulub,] Mexico. The impact killed 70% of all species on Earth, including the dinosaurs. An impact of that size would have had devastating effects, and the geological record gives us some indication of what happened. The asteroid hit in water, creating mega-tsunamis reaching from southeastern Mexico all the way to Texas and Florida and up a shallow interior ocean that covered what is now the Great Plains. The blast would have thrown chunks of the asteroid and Earth so far that they would have briefly left the atmosphere before falling back to the ground.

This stony asteroid, which has an estimated diameter of around 3,600 feet (1.1 km) and passed within 1.2 million miles (1.9 million km) of Earth in 2022, has around a 0.0151% chance of coming within one Earth-moon distance over the next millennium, the team calculated. This makes it around 10 times more likely to impact as the next riskiest in the category, 20236 (1998 BZ7), which has a 0.001% probability of coming closer to us than the moon. (The moon orbits, on average, about 239,000 miles, or 384,600 km, from Earth.)

The point of this scenario is that often there is no symmetry between mitigating a coming disaster and addressing the damage that such a disaster might inflict. In the Chicxulub Event scenario, the impact killed 70% of all species on Earth but none of these species had the technology to detect its coming and prevent the collision. Despite the very low probability of the event, it was not zero. Our species now has the capacity to learn how to deflect such a collision, but it takes time and resources to develop such technologies. These trade-offs between spending now to mitigate future disasters or doing nothing now with the “hope” that (at least in our lifetimes) the disaster will not take place, should not be an option. This type of prioritization is also taking place on a smaller scale. When I was teaching climate change in school, I often heard declarations that if our world continues to trade the future well-being of our children for our present comfort, we should not have children!

Following my definition, my Now started around the beginning of WWII with the Nazi invasion of Poland. I was born into a Jewish family and as a result, my Now also started with the Holocaust. The pairing of global threats with the Holocaust seems to me a necessity that I owe my grandchildren.

I finished writing this blog on Sunday, December 14th. We had the first sticking snow of the season, the first evening of Hanukkah, and my 24th wedding anniversary. Around the same time, I ordered two recent books, Fateful Hours: the Collapse of the Weimar Republic by Volker Ullrich and 1929: Inside the Greatest Crash in Wall Street History—and how it shattered a Nation by Andrew Ross Sorkin and Penguin Audio. Both books took place just before the start of my now, with a hidden question mark about history repeating itself. In the last two blogs of this year, I will try to explore this same premise.