(Source: Reddit)

(Source: Reddit)

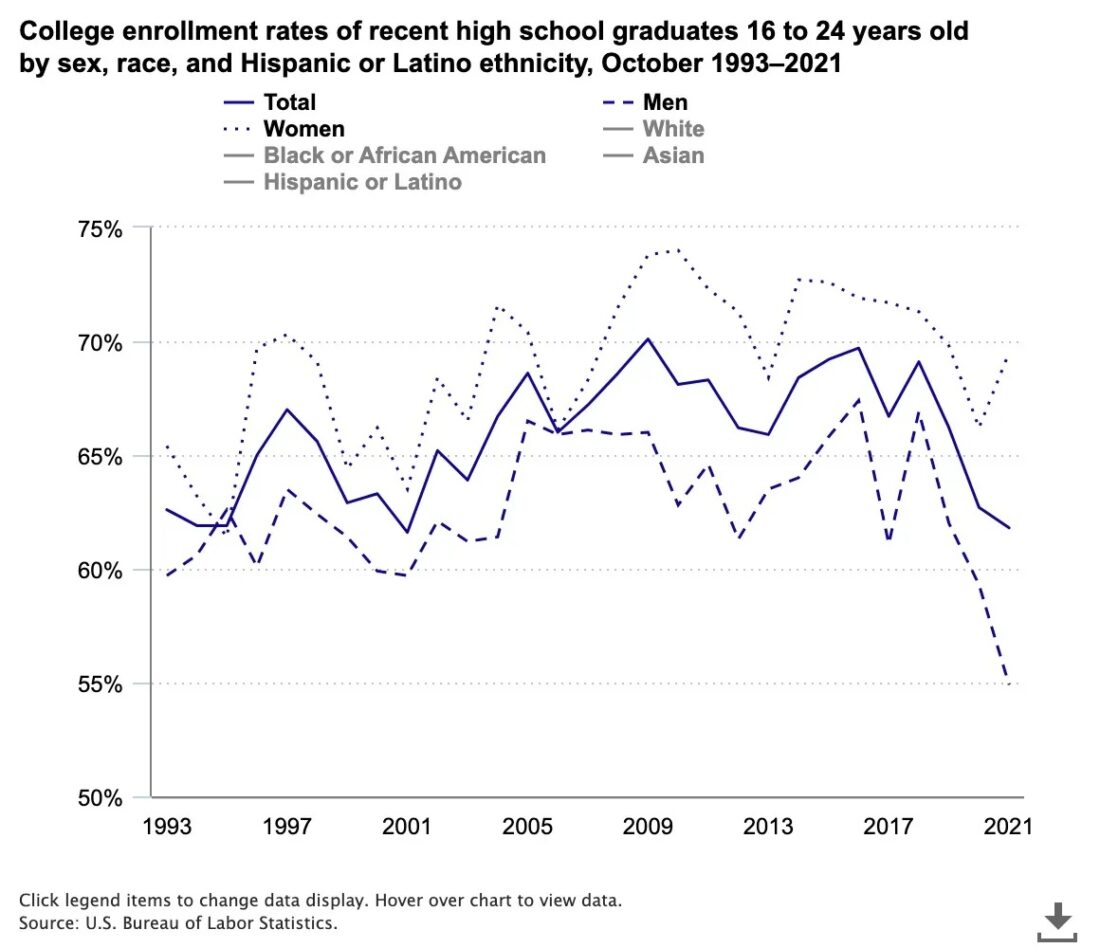

Last week’s blog was focused on some of the actions that colleges are taking to counter the recent decline in enrollment. The key entry on that blog was not the final steps that some colleges find themselves having to take as a result of the declining resources (such as closing the colleges, closing programs with low enrollment, joining other schools, etc.). Instead (or in addition), I was interested in the way they are changing their targets to a different student audience. This sentiment was expressed in the Chronicle of Higher Education with the following two paragraphs:

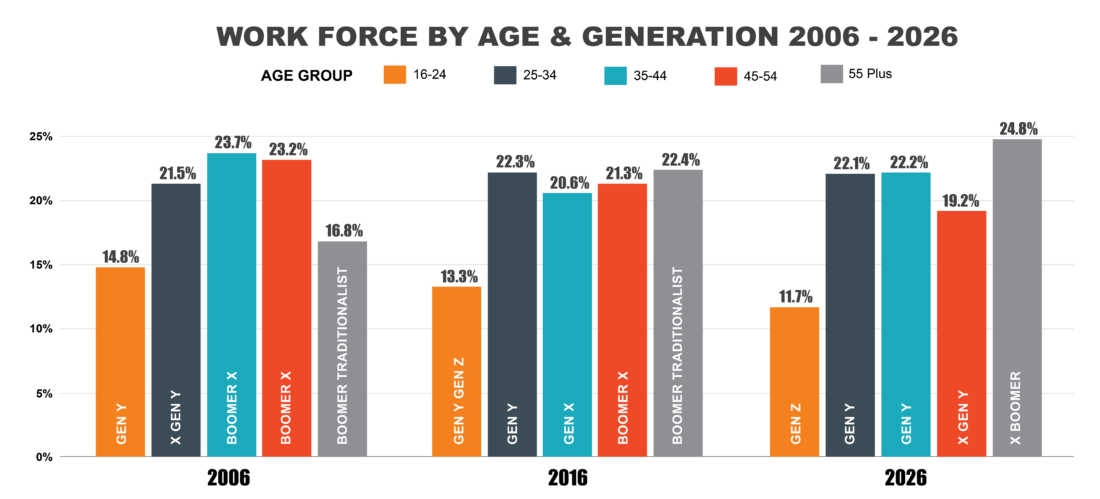

Colleges typically prioritize those who are preparing to enter the workforce, teaching them what they’ll need to know in order to thrive in a working society. But, what about those already in the workforce? Those left behind by sudden changes in technology and changing labor expectations? Historically, universities have prioritized educating those between 18- and 24-years-old.

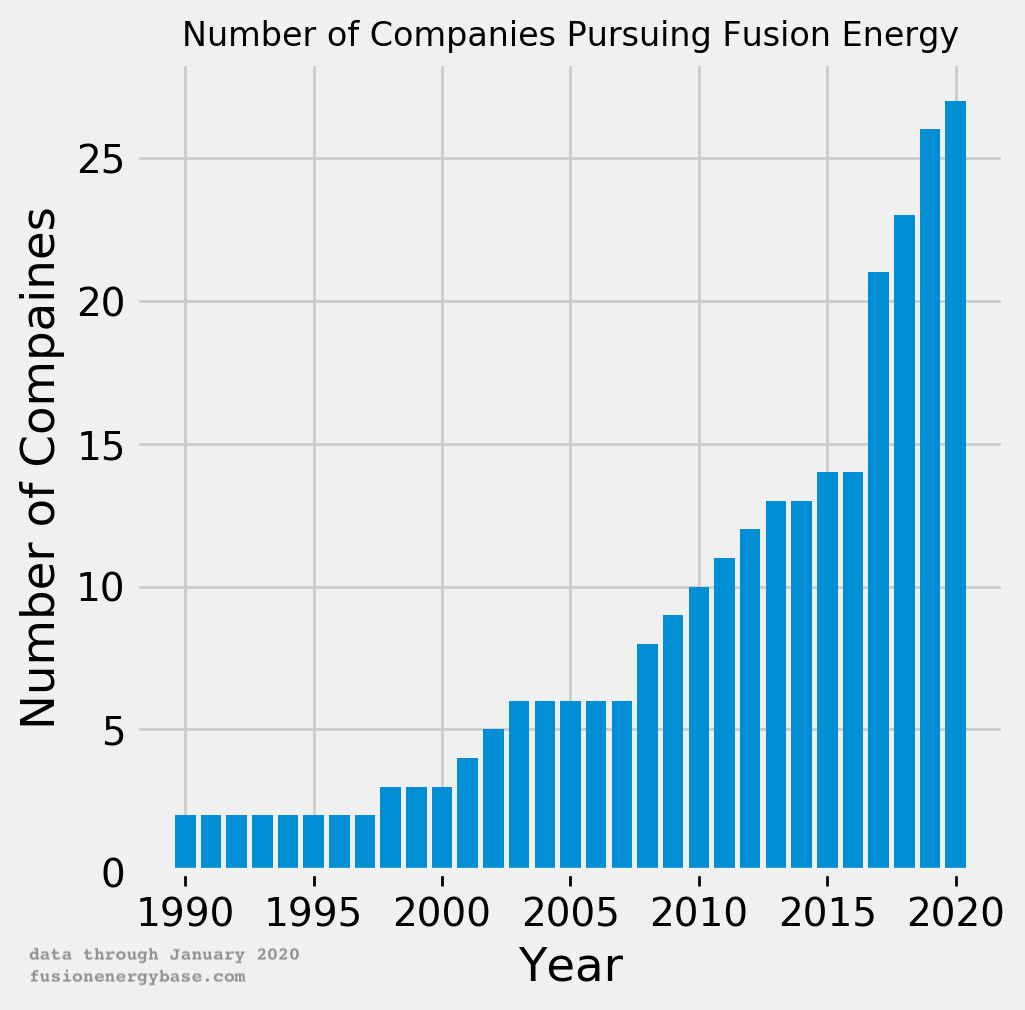

But, the needs of the workforce change over time. This is especially true in an age where AI and automation are making inroads into every industry. It’s time colleges adapt with the workforce. And upskilling may be the answer — whether that comes in the form of micro credentialing, skills-based training, or whatever else.

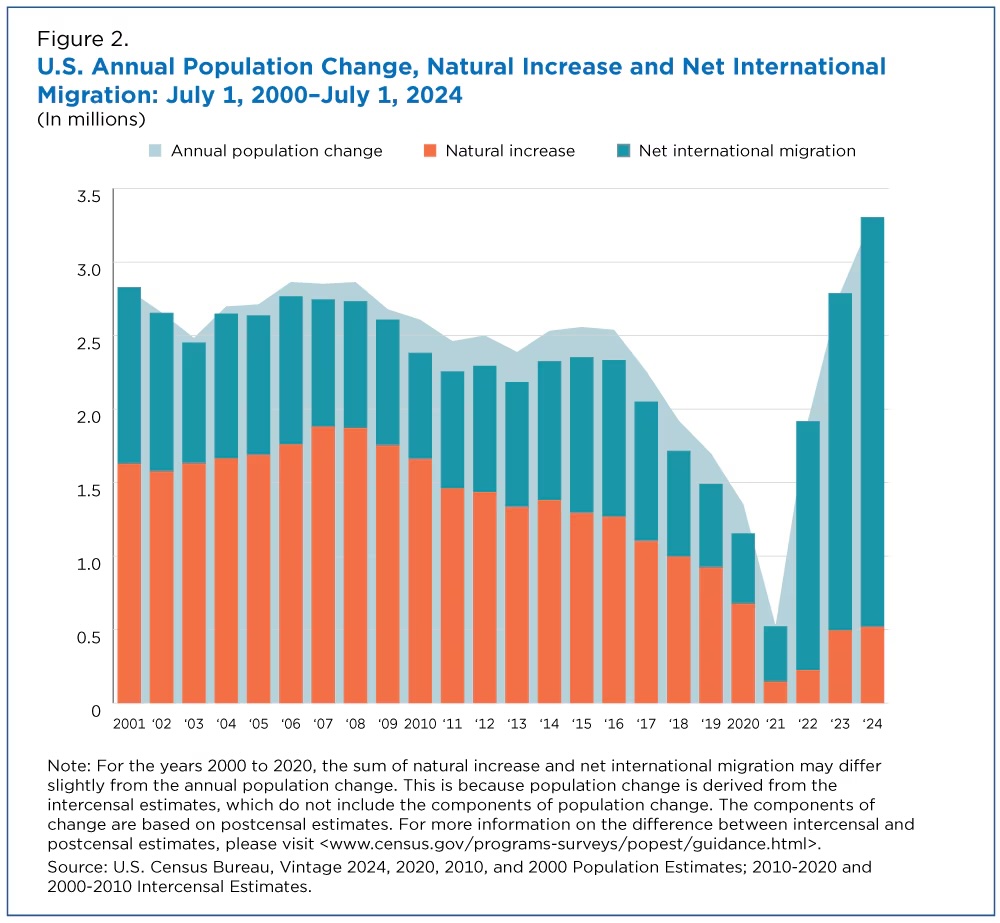

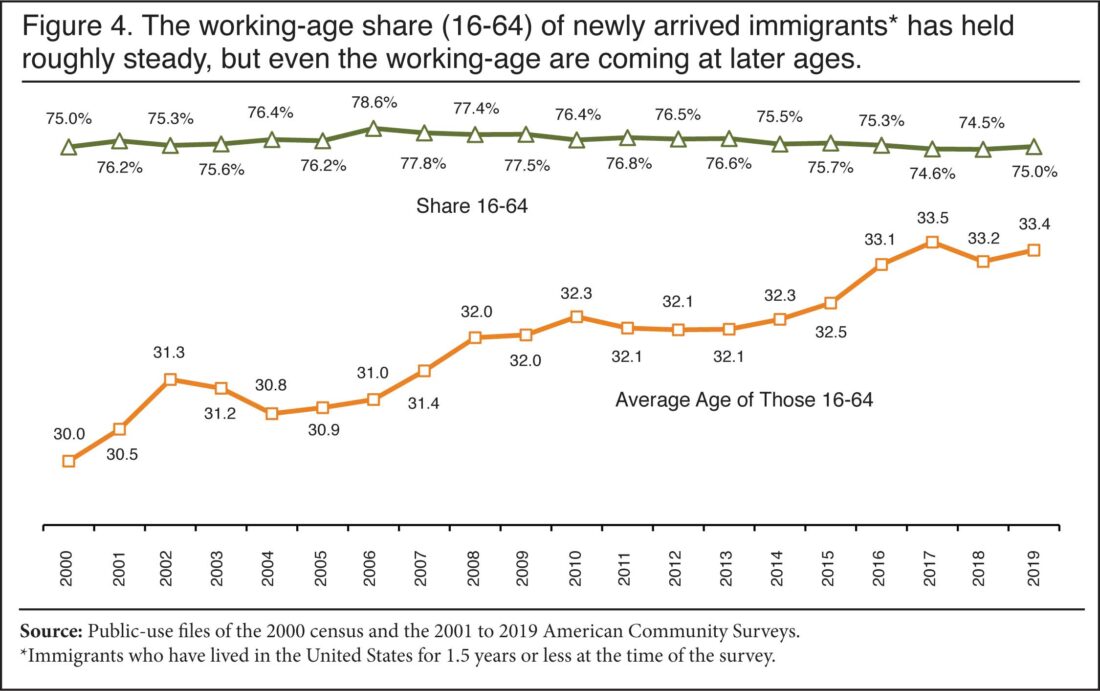

The recommendation originates from the accelerating decrease in the global fertility rate, the reliance on immigration for growth (at least in rich countries), and the resulting changes in the age distribution of the work force. The need is summarized by AI (through Google) in the following way:

The average number of careers changes a person will make during their working life is 5–7. This is due to an increasing number of career options, and 30% of the workforce changes jobs every year.

The number of jobs changes a person makes decreases with age:

-

-

-

- 18–24: People change jobs an average of 5.7 times

- 25–34: People change jobs an average of 2.4 times

- 35–44: People change jobs an average of 2.9 times

- 45–52: People change jobs an average of 1.9 times

What adds to the difficulty for such changes is the inherent tension in today’s higher ed institutions between fluctuating enrollment, budget, and faculty tenure. The present situation at the University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, demonstrates the issue:

Chancellor Mark Mone revealed the layoffs in a letter sent Monday to faculty and staff.

The job cuts come after the UW System said it will close its campuses in Waukesha and Washington counties.

In addition to the layoffs, Mone recommended shutting down UW-Milwaukee’s College of General Studies and its three academic departments: Arts & Humanities, Math & Natural Sciences, and Social Sciences & Business.

“I am deeply saddened by this scenario and wish it were not occurring. However, proceeding with the proposal is aligned with our mission and is the most responsible decision for UWM’s future,” Mone said in the letter.

The UW Board of Regents must approve the cuts.

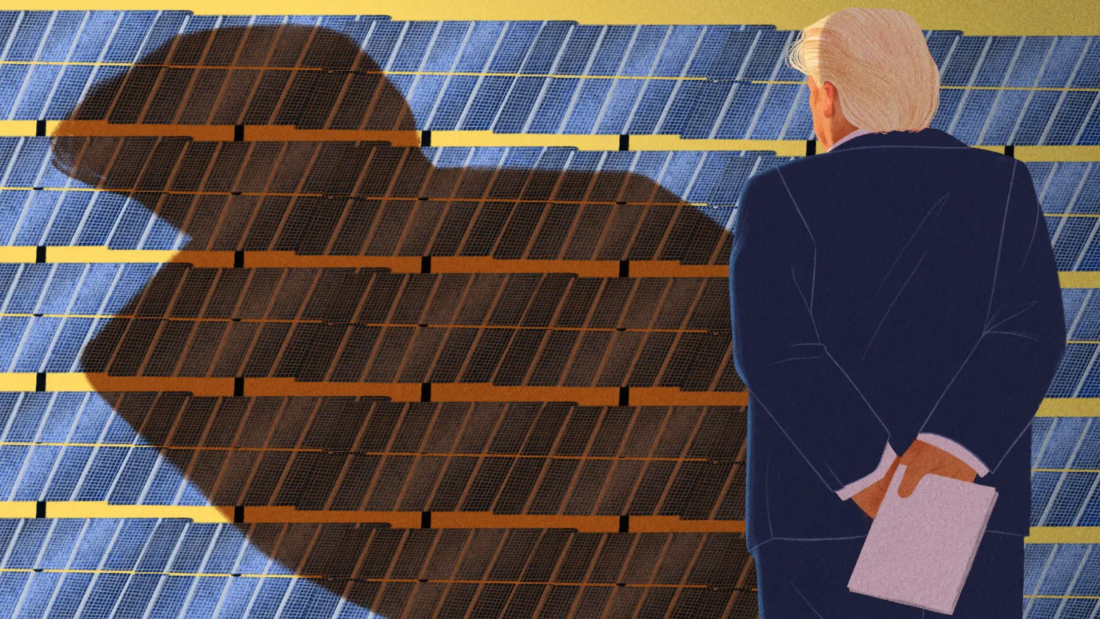

This blog will be posted one day after President Trump is inaugurated. Many expect a fast-changing four years. This blog is trying to examine how universities adapt to fast-changing realities—a process that will be interesting to follow. For background, you can see my previous writing on the topic; just put “changing realities” into the search box and focus on colleges. You can start with the blogs from May 2023 that focused on strategic plans for climate change. Now, we are facing broader horizons, including changes in fertility and mass digitization, along with AI and quantum computing. Many of these changes are global; many will likely be affected by the new administration following Trump’s inauguration.

The most sensitive part of the higher education sector—and therefore that most likely to be impacted by the new administration—is the accreditation sector (Trump’s Vision for College Accreditation Could Shake Up the Sector):

Overhauling higher-education accreditation could be on the agenda for conservative lawmakers and policy mavens now that Donald J. Trump has been re-elected president.

Trump and his allies have floated a number of changes, such as barring accreditors from requiring that colleges adhere to diversity, equity, and inclusion standards. Republicans have also proposed creating new accrediting agencies that promote conservative values and allowing state governments to take on the role of accreditors.

Colleges have to be accredited for their students to be eligible for federal student aid, such as loans issued by the Education Department and Pell Grants for students from low-income families. That role as a gatekeeper of federal dollars has put accreditors in the crosshairs of groups across the ideological spectrum that see the organizations as a barrier to change and improvement.

Below is a summary of the governance in my state (NY) that controls accreditation policies:

Oversight of degree-granting institutions in the United States is often thought of as the responsibility of a triad comprising state agencies, nongovernmental accrediting bodies, and the U.S. Department of Education (USDE). All degree-granting institutions that have a physical presence in New York must have authorization from the Board of Regents to operate as a college or university. This applies to both New York institutions and those based out-of-state. The State Education Department reviews, approves, and registers all individual programs of study leading to degrees and credit-bearing certificates according to standards of academic quality in the Regulations of the Commissioner of Education. Together, Regents authorization to confer degrees and State Education Department program registration make up the mandatory State approval process.

During my career as a college professor, I oversaw the assessments in my department, Physics. I am now a retired Professor Emeritus and hope to continue being of some use in this area. For more details on the expected and needed changes in higher education, I will focus on my school, the City University of New York (CUNY) as an example. CUNY is a federated university that prides itself on being the largest urban university in the US. Figure 1, at the top of this blog, shows the various colleges that are affiliated with CUNY. I have used CUNY as an example extensively in the 12 or so years that that I have been writing this blog. For almost 50 years, I was a member of two colleges: Brooklyn College, which is shown on the figure above, and the CUNY Graduate Center, which is not shown. Most public universities in the US are federated universities that spread geographically and whose missions are to serve a broad spectrum of state citizens. Many of the CUNY examples that will be used here apply to many other schools.

The agency that oversees CUNY’s accreditation is the Middle States Commission on Higher Education (MSCHE). CUNY’s affiliation with MSCHE is summarized below:

CUNY colleges, as well as the Graduate School and University Center, receive their institutional accreditation from the Middle States Commission on Higher Education (MSCHE or Middle States). MSCHE examines each institution as a whole, rather than specific programs within institutions.

The standards that the accreditation commission uses also change constantly. The most recent set is in MSCHE’s Fourteenth Edition.

Every one of the colleges affiliated with CUNY is assessed independently by the same commission. The accreditation commission bases its judgment mainly on self-assessments. AI (through Google) defines school assessment in the following way:

The assessment process is twofold — measuring student outcomes and an institution’s ability to provide students with the skills and knowledge they need to start meaningful careers. In return for holding students to a high standard, institutions receive actionable data to inform future improvements.

MSCHE accredits its schools every 10 years. Most of the work is based on a periodic self-study report that the schools produce. Below, I am giving the table of contents of the most recent self-study report from Brooklyn College. The hierarchical structure of the federated schools is covered in the reports of the participating colleges. The assessment of student learning is an integral part of the syllabus that needs approval by the Faculty Council. General Education, which consists of about 25% of the curriculum, is managed on a university level, again, anchored on common student learning. The Self-Study is a long document that is transparent to students and faculty. Go through this index to find what is of concern and what is not.

Table of Contents

Executive Summary……………………………………….1

INTRODUCTION……………………………………………5

I.1 Overview of Brooklyn College…………………… 5

I.1.1 Trends in Enrollment…………………………….. 8

I.1.2 Faculty and Staff ………………………… 9

I.1.3 Trends in Affordability and Student Success ………………………………………………………… 12

I.2 Significant Changes and Challenges Since the 2009 Self-Study ……………………………………. 12

I.2.1 Leadership ………………………………. 12

I.2.2 Academic Affairs Organizational Structure ………………………………………………………….. 13

I.2.3 New Strategic Plan ……………………………… 14

I.2.4 Significant Curricular Changes ……………. 15

I.2.5 Facilities…………………………………………….. 15

I.3 Brooklyn College’s Recent MSCHE History ………………………………………………………………….. 16

I.4 The 2016-2019 Self-Study Process……………. 17

I.5 Organization of this Report …………………….18

CHAPTER 1………………………………………………….19

1.1 Introduction ………………………………………….. 19

1.2 Mission …………………………………………………. 19

1.2.1 Mission Development: Strategic Planning Process ……………………………………………………… 20

1.2.2 Alignment with CUNY………………………….. 21

1.2.3 Awareness of Mission Statement …………. 22

1.3 Quality of a Brooklyn College Education …. 22

1.4 Diversity of the Brooklyn College Community …………………………………………………………… 23

1.5 Affordability of a Brooklyn College Education …………………………………………………………… 24

1.6 Integration with Community …………….. 26

1.7 Supporting the Mission…………………… 27

1.8 Recommendations Aligned with the College’s Strategic Plan ………………………………………. 27

CHAPTER 2 ………………………………………………. 28

2.1 Introduction …………………………………………. 28

iii

2.2 Ethical Conduct, Intellectual Freedom, Freedom of Expression, and Respect for Intellectual

Property ……………………………………………………. 28

2.3 Creating a Climate of Respect ………………… 29

2.4 General Policies that Govern Students, Faculty, and Staff ………………………………………. 30

2.5 Policies Governing the Student Experience ………………………………………………………………….. 31

2.6 Faculty Personnel Policies ……………………… 33

2.6.1 Promotion and Tenure/Certificate of Continuous Employment (CCE) …………………… 34

2.6.2 Professional Development …………………… 35

2.6.3 Faculty Complaints and Grievances Procedures ………………………………………………… 35

2.7 Staff Personnel Policies …………………………. 35

2.7.1 Staff Career Advancement/Professional Development …………………………………………….. 36

2.7.2 Staff Complaints and Grievances ………… 36

2.8 Recommendations Aligned with the College’s Strategic Plan ……………………………………………. 36

CHAPTER 3 ……………………………………………….. 37

3.1 Introduction …………………………………………. 37

3.2 Academic Program Offerings ………………… 37

3.3 Faculty ………………………………………………… 39

3.3.1 Faculty Qualifications and Diversity ……. 40

3.3.2 Faculty Qualifications and Assessment ………………………………………………………………….. 41

3.4 General Education ………………………………… 44

3.5 Graduate Education ……………………………… 48

3.6 Academic Support ………………………………… 48

3.6.1 Academic Services and Resources…………………………………………………… 48

3.6.2 Support for Specialized Student Groups ………………………………………………………………….. 49

3.7 Recommendations Aligned with the College’s Strategic Plan …………………………………………….. 51

CHAPTER 4 ……………………………………………….. 52

4.1 Introduction………………………………………….. 52

4.2 Admissions, Retention and Graduation ….. 52

4.2.1 Momentum ………………………………………… 53

4.2.2 Retention and Graduation ………………….. 55

4.3 Student Information and Records ………….. 58

4.4 Adequacy and Accessibility of Web-Based Information ………………………………………………. 59

4.5 Access to Face-to-Face Support ……………… 60

4.6 Adequacy of Co-Curricular and Extra-Curricular Activities …………………………………… 62

4.7 Adequacy of Staff in Student Support Areas …………………………………………………………………. 64

4.8 Recommendations Regarding Standard IV and Strategic Plan Alignment ……………………… 64

CHAPTER 5 ……………………………………………….. 65

5.1 Introduction ………………………………………….. 65

5.2 Current Status of Assessment at Brooklyn College: Linkages Among Educational Goals and

Programs ………………………………………………….. 65

5.2.1 Overview of Educational Goals, Interrelationships, Alignment with Mission …. 66

5.2.2 Organization of Assessment ………………… 66

5.2.3 Systematic Assessment, Preparation of Students, and Sustainability ……………………….. 68

5.2.4 Supporting and Sustaining Assessment and Communicating Results to Stakeholders ……… 72

5.3 Using Assessment Results for the Improvement of Educational Effectiveness …… 73

5.4 Periodic Assessment of the Effectiveness of Assessment ………………………………………………… 80

5.5 Success of Graduates …………………………….. 80

5.6 Recommendations Aligned with the College’s Strategic Plan ……………………………………………. 82

CHAPTER 6 ………………………………………………. 83

6.1 Introduction …………………………………………. 83

6.2 Linkages among Institutional Objectives, Assessment, Planning and Resource Allocation . 83

6.3 General CUNY Budget Allocation Process for Senior Colleges …………………………………………… 85

6.3.1 Overview of the Brooklyn College Tax Levy Budget ………………………………………………………. 86

6.4 The Financial Planning and Budget Process ………………………………………………………………….. 87

6.4.1 Operating Budget Planning Processes …………………………………………………………………. 87

6.4.2 Capital Budget Planning …………………….. 89

6.4.3 Technology Budget Planning ………………. 89

6.4.4 Fiscal and Human Resources ……………… 90

6.5 Alternative Sources of Funding and Revenue ………………………………………………………………….. 91

6.5.1 Income Funds Reimbursable (IFR) ………. 91

6.5.2 Non-Tax Levy ……………………………………. 92

6.5.3 Auxiliary Enterprise Corporation (AEC) …………………………………………………………………. 92

v

6.5.4 Brooklyn College Foundation (BCF)………………………………………………………… 92

6.5.5 CUNY Research Foundation (RF) ……….. 92

6.6 Improvements to Administrative Processes ………………………………………………………………….. 93

6.6.1 College Facilities ………………………………… 93

6.6.2 Improving the Procurement Department ………………………………………………………………….. 94

6.7 Annual Audits ………………………………………. 95

6.8 Recommendations Aligned with the College’s Strategic Plan ……………………………………………. 95

CHAPTER 7 ……………………………………………….. 97

7.1 Introduction ………………………………………….. 97

7.2 Governance ………………………………………….. 97

7.2.1 Changes to Local Governance and Bylaws ………………………………………………………………….. 99

7.3 Administration ……………………………………… 99

7.3.1 Implementation of a Five-School Structure ………………………………………………………………… 100

7.3.2 Technology to Support Administration in the Delivery of Services to Students ……………. 102

7.3.3 Assessment of the College President, College Leadership and Administration …………………. 104

7.4 Recommendations Aligned with the College’s Strategic Plan …………………………………………… 105

If you look at the mission statement (page 19), you will get to another long document that takes you to the Strategic Plan. Since Brooklyn College is part of CUNY, both its mission and strategic plan are aligned with CUNY’s. In these documents, you will have an easy time finding the word “excellence.” However, it’s a bit harder to find the word “future” or references to how graduates are adapting to the changing realities that confront them. Future blogs will focus on these important issues.

(Source:

(Source:  (Source:

(Source:  (Source: Lauren Pyke,

(Source: Lauren Pyke,

(Source:

(Source: