Thursday, September 6th in New York City was really hot and humid with temperatures well above 90oF. The next day the temperatures plunged to mid-70s and stayed there for several days, with almost constant rain. Today (Saturday, September 15th), while I am writing this, the weather here is fine but Hurricane Florence is flooding the Carolinas and Typhoon Mangkhut is doing the same to the Philippines as it makes its way to China. We still haven’t estimated the number of deaths and the full economic damages these storms will inflict.

Was the NYC heat wave on September 6th the last one of this year? Who knows? Why don’t we give names to heat waves the way we do with hurricanes and typhoons? I grew up in Israel, which is in the Eastern Mediterranean and experiences wet winters and dry summers. Israelis give names to the first rain (Hayorre) and the last one (Malkosh). There are first rain celebrations that sometimes include songs. I am not familiar with any celebrations of the last rain, but then it would be harder to pin down – how do you know that this rain is the last one? You could speculate with the help of recent history and an almanac but you might be wrong.

My fall semester started at the end of August. We distinguish it from the spring semester that starts around the end of January – but how do we come up with dates for the seasons? Does the weather repeat itself so exactly in corresponding years? Are the designations of seasons the same all around the world? I ask these sorts of classical questions at the beginning of my Cosmology class and usually get mixed answers. Students hearing these questions for the first time almost always say that summer comes when we are closest to the sun while winter happens when we are farthest away. I pose these questions in the middle of a brief survey of the history of astronomy. We discuss Kepler’s laws – especially Kepler’s First Law, which states that the planets orbit the sun in an elliptical orbit rather than a circular orbit as was taught previously. With the sun being at one of the two foci ellipse (there’s nothing at the other), their answers make perfect sense – until we then ask why in that case do we have summer in NYC while the Australians have winter in Melbourne, and vise versa?

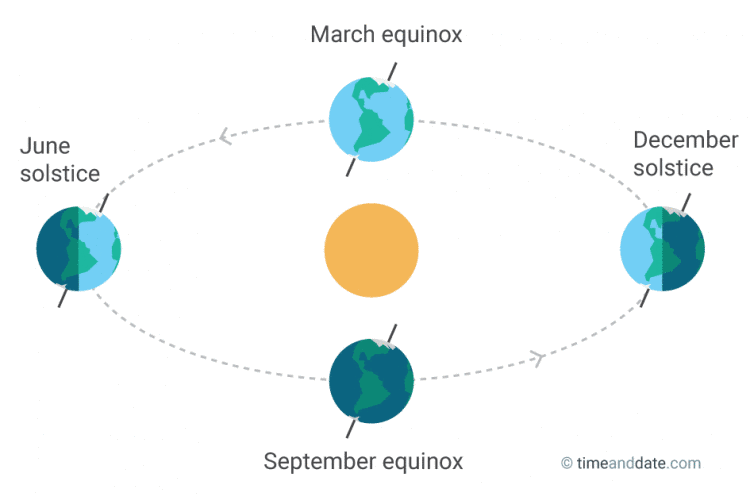

The correct answer rests in Figure 1, with an explanation given below:

The Earth’s axis is slightly tilted in relation to its orbit around the sun. This is why we have seasons

Since the year has 12 months, each season lasts about three months. However, the dates when the seasons begin and end vary depending on whom you ask. Two methods are most commonly used to define the dates of the seasons: the astronomical definition and the meteorological definition

The astronomical definition uses the dates of equinoxes and solstices to mark the beginning and end of the seasons.

Spring begins on the spring equinox;

Summer begins on the summer solstice;

Fall (autumn) begins on the fall equinox; and

Winter begins on the winter solstice.

Figure 1 – Earth’s orbit around the sun.

Figure 1 – Earth’s orbit around the sun.

According to the meteorological definition, the seasons begin on the first day of the months that include the equinoxes and solstices:

Spring runs from March 1 to May 31;

Summer runs from June 1 to August 31;

Fall (autumn) runs from September 1 to November 30; and

Winter runs from December 1 to February 28 (February 29 in a leap year).The question which definition to use divides countries and regions around the world. For example, Australia and New Zealand use the meteorological definition, so spring begins on September 1 each year. In many other countries, both definitions are used, depending on the context.

Ireland uses an ancient Celtic calendar system to determine the seasons, so spring begins on St Brigid’s Day on February 1. Some cultures, especially those in South Asia have calendars that divide the year into six seasons, instead of the four that most of us are familiar with.

In Finland and Sweden, the dates of the seasons are not based on the calendar at all, but on temperatures. Here, spring officially begins when the average temperature rises above 0 °C

(32 °F). This means that the seasons within each county start and end on different dates, depending on the regions and their climate.

Solstice in Figure 1 is defined as the point in the Earth’s orbit at which the sun is at the greatest distance from the celestial equator while the equinox is defined as the shortest distance (when the Earth actually sits on the equator). The ellipse in Figure 1 is exaggerated for clarity. The difference between the elliptical orbit and a circle is defined by the ratio of the long axis to the short axis. In a circle both axes are the same. In the Earth’s orbit the ratio deviates from a circle by about 3%.

As you can see, the dates of the seasons are approximately defined by the position of the Earth relative to the sun but the corresponding weather is not. The weather in the seasons is instead determined by the tilt of the Earth’s axis in relation to the path defined by the solar orbit. This tilt means that the northern and southern hemispheres are alternately exposed to the direct power of the sun, so summer in the northern hemisphere corresponds to winter in the southern hemisphere.

Focusing on a particular spot in the northern hemisphere, the definitions of the seasons in Sweden and Finland are interesting. The Finnish seasons are as follows:

Winter – Less than 0oC (32oF)

Spring – between 0o and 10oC (50oF)

Summer – more than 10oC

Fall – between 0o and 10oC

The listed temperatures are for averages from the middle of the country.

There is a similar quandary here to the Israeli naming of the last rain: how do you calculate averages ahead of the events?

This unique specificity in Finland and Sweden piqued my interest especially because I will be visiting Lapland in January to observe the Northern Lights among other things. More importantly though, can we use the start and end dates of these seasons as another measure of the impact of climate change? Given what we’ve seen so far and our projections for the future, their timing should shift as the temperature changes. I tried to find the recent history of the timing of the seasons there but didn’t have any success. Once I get there I will try to consult my local guides for data.

Back to naming individual weather events:

Officially, the science community only names tropical cyclones. However, in the US, the National Weather Service assigns names to hurricanes due to their immense impacts on life and property; there is a general belief that naming them garners more attention and gives governments and residents more time to prepare.

Heat waves don’t get names. In most cases, their geographical distribution is similar to that of hurricanes but as of yet they have not inflicted as much damage. Also, there is less that people can do in terms of last-minute preparations. However, naming them in the summer might be fun. We are open to suggestions. Heat wave Hades, anyone?

This is nicely worded and helpful, kudos. I appreciate the way you explain points succinctly. It’s useful info and I deem you worth sharing.