Figure 1 – Doomsday Clock

Three weeks ago (before Charlottesville) I summarized the climate-change-related events that took place during my July vacation and promised to expand upon those issues. Given my necessary digression, I am reposting some of those elements here for easy reference. I am also including the relevant section of a critique of Al Gore’s “An Inconvenient Sequel” movie, in which the critic equates his doomsday predictions to disaster porn.

Here’s a segment of my outline:

Distant Future: the end of the present century – i.e. my definition of “now” (the projected lifespan of my grandchildren):

- What can we do to make life at the end of the century as sustainable as we possibly can? – A repeated question that follows almost every presentation on climate change.

- Doomsday

- “What do you call the last of the species?”

- David Wallace-Wells’ publication in New York Magazine.

- A scientific analysis of worst-case impacts recently published in the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) journal.

- Paul Ehrlich’s paper, “Biological annihilation via the ongoing sixth mass extinction signaled by vertebrate population losses and declines” also published in PNAS.

- Discussions

- Al Gore’s new movie

- “P.A. to Give Dissenters a Voice on Climate, No Matter the Consensus”

However, to incorporate some of the sense of conflict that has been playing out between optimists and pessimists, here’s part of a joint critique of Al Gore’s new film and the David Wallace-Wells piece:

“An Inconvenient Sequel,” which opened in select cities on Friday and will open nationwide next week, arrives on the heels of a widely shared New York magazine article by David Wallace-Wells. The piece describes, in dramatic terms, the worst-case repercussions of climate change. “Absent a significant adjustment to how billions of humans conduct their lives, parts of the Earth will likely become uninhabitable, and other parts horrifically inhospitable, as soon as the end of this century,” Wallace-Wells writes. Some climatologists objected to the article’s characterizations of their work, but the real controversy centered on its approach. Michael Mann, the director of the Earth System Science Center, at Pennsylvania State University, declared that he was “not a fan of this sort of doomist framing,” and the sociologist Daniel Aldana Cohen described it as “climate disaster porn.”

I teach a graduate course on Physics and Society in which climate change and the transition to the Anthropocene are key components. One of the students last semester was clearly upset and left the course in the middle of the semester; she hated the idea of what she saw as doomsday scenarios masquerading as science. On the other hand, if we want to impact the future in such a way as to negate these predictions, we need to work on understanding how best to approach mitigation.

I didn’t like the Al Gore movie for a different reason. In my opinion, it did not put enough emphasis on the predicted impacts of business as usual scenarios – how a continuation of the ways in which we achieve our current standards of living (e.g. our present energy mix, population growth, water use, etc.) is causing/will cause destruction of the physical environment. “An Inconvenient Sequel” focused almost exclusively on climate events and Al Gore’s activities in the time period following his Oscar-winning first film. There was no discussion at all about how we figure out human contributions to these climate events. This omission detracts a considerable amount of credibility from the advocacy in the movie. It is difficult to make movies about the future or about how we attribute blame, but it is not impossible. His first movie did a much better job at including these important elements.

The two figures in this blog summarize some of the challenges. Figure 1 shows a doomsday clock:

The Doomsday Clock is a symbol which represents the likelihood of a man-made global catastrophe. Maintained since 1947 by the members of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists‘ Science and Security Board,[1] the Clock represents an analogy for the threat of global nuclear war. Since 2007, it has also reflected climate change[2] and new developments in the life sciences and technology that could inflict irrevocable harm to humanity.[3]

The Clock represents the hypothetical global catastrophe as “midnight” and The Bulletin’s opinion on how close the world is to a global catastrophe as a number of “minutes” to midnight. Its original setting in 1947 was seven minutes to midnight. It has been set backward and forward 22 times since then, the smallest-ever number of minutes to midnight being two (in 1953) and the largest seventeen (in 1991). As of January 2017[update], the Clock is set at two and a half minutes to midnight, due to a “rise of ‘strident nationalism‘ worldwide, United States President Donald Trump‘s comments over North Korea, Russia, and nuclear weapons.”[4][5] This setting is the Clock’s second-closest approach to midnight since its introduction.

Throughout its conceptual existence, the clock – although it allows for the possibility of other scenarios – has been heavily weighted towards world annihilation by way of nuclear holocaust (see February 2, 2016 blog). Here our focus will be climate change.

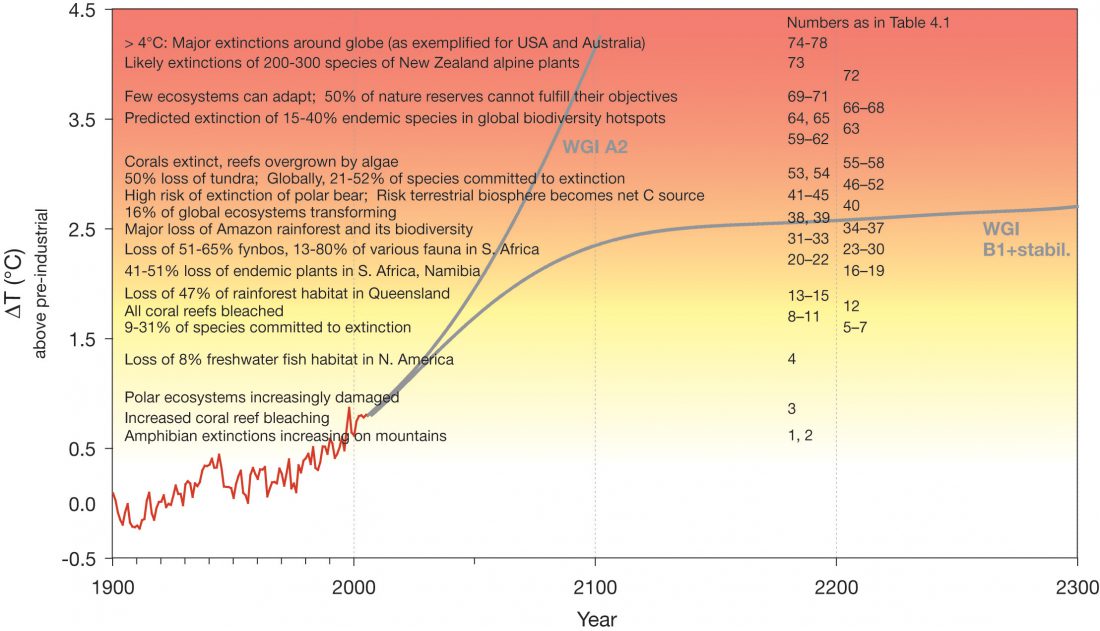

Figure 2 – IPCC projections of future climate change impacts based on two different scenarios

Figure 2 – IPCC projections of future climate change impacts based on two different scenarios

Figure 2 shows the IPCC’s projected impacts of climate change as estimated in its Fourth Assessment Report ten years ago (September 24, 2012 and October 14, 2014). One can see in the figure a gradual transition from yellow to orange. As we enter into the dark orange region, we see:

Few ecosystems can adapt; 50% of nature reserves cannot fulfill their objectives. Predicted extinction of 15 – 40% endemic species in global biodiversity hotspots.

This continues, as we progress further into the dark orange zone, with:

>4oC: Major extinctions around globe (as exemplified for USA and Australia). Likely extinctions of 200 – 300 species of New Zealand alpine plants.

We can arbitrarily define the transition from yellow to orange as the transition into end-of-the-world conditions and try to figure out why a respected sociologist and others labeled it disaster porn. Not being an expert in that subject or the use of the phrase, I assume that it stems from porn being considered “cheap” and not “real.” It is obvious, however, that porn is very real to both its participants and producers and it comes with a variety of prices. My job here is to make a case that doomsday scenarios cover a similar range of spectra – from viscerally frightening situations with limited quantitative details to rigorous scientific quantitative evaluations. All of these descriptions seek to encourage the masses to actively seek out ways to immediately implement policies and activities that could keep any sort of doomsday at bay for as long as possible.

Stay tuned and let me know where I succeed and where I fail.

let’s be honest here: nowadays, anyone can be a porn star, just a camera and a computer. It’s new times, I’m not used to it yet in now

let’s be honest here: nowadays, anyone can be a porn star, just a camera and a computer. It’s new times, I’m not used to it yet.