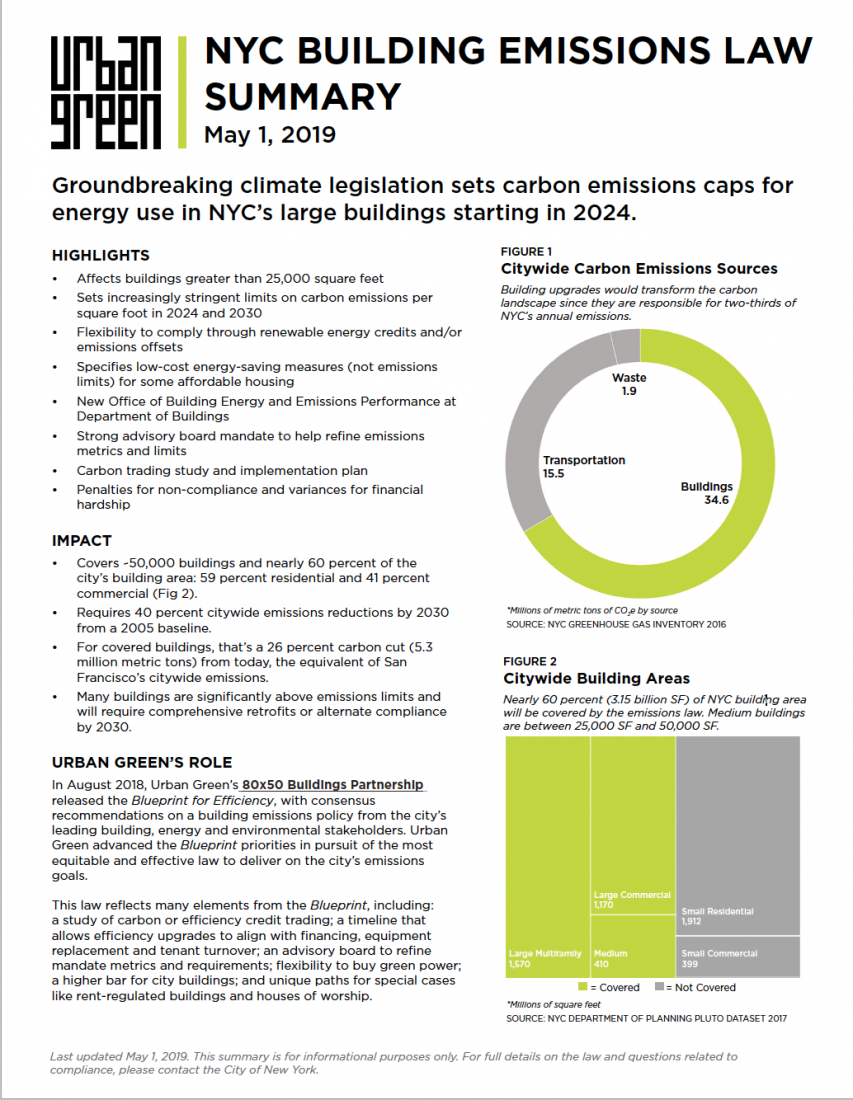

In urban environments, buildings are major contributors to climate change. In fact, according to the NYC Greenhouse Gas Inventory of 2016, they are responsible for two-thirds of New York City’s annual emissions. I have been looking at mitigation efforts of both my campus and my apartment. When I have discussed mitigation of university campuses, I have made the distinction between new and old buildings. Changes in construction and renovation stem from three forces: compulsory, top-down change, as mandated by legislation; collective self-motivation, and aspiration.

I live and work in New York City. In the compulsory column, we can now add the city council’s decision (see my June 4th blog), mandating landlords are required to retrofit all buildings larger than 25,000ft2 (2322 m2) with new windows, heating systems, and insulation by 2024. These changes should cut emissions (in comparison to calculations from 2005) by 40% in 2030, and double those cuts by 2050, for a total estimated reduction of about 80%. Landlords face heavy fines if they fail to meet these targets. This basically means that by 2050, the city’s buildings will be almost zero carbon, which is in line with the C40 initiative (June 4th blog) that ex-NYC mayor Bloomberg has coordinated (and partially financed). This is an example where the compulsory mandate and the aspirational mandate coincide (most likely not by accident— NYC is part of the C40).

In case this initiative takes hold, it is not difficult to predict that self-motivation will also play a role: somebody will probably form a well-publicized list that will rank buildings in a similar way to how the Sierra Club ranks campuses, prompting building owners to take action to climb these lists. Not only will doing so reflect good values and the desire to avoid fines, they may well impact the underlying real estate values.

The new NYC law, now known as Local Law 97 for 2019 or “NYC Building Emissions Law” is detailed and complex. You can read the summary at the bottom of the blog or by going here.

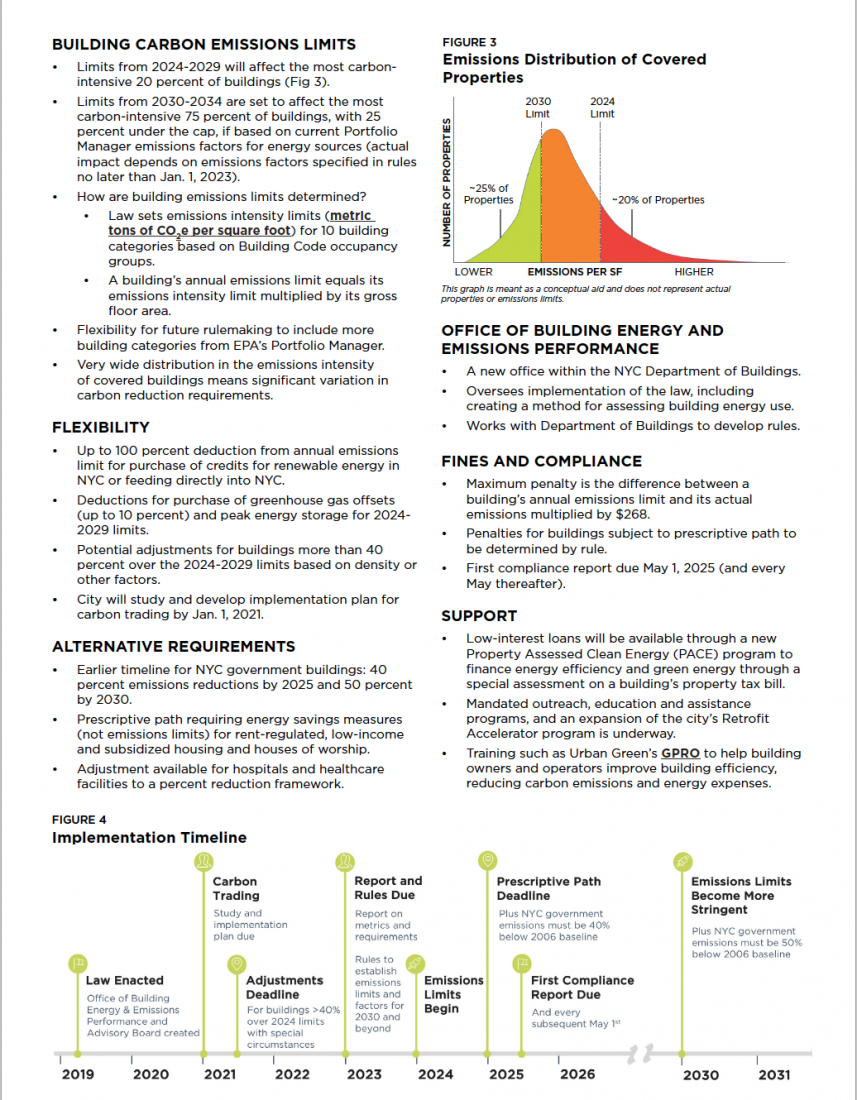

As indicated at the bottom of the second page of the summary, the emission limits begin in 2024 and the first compliance report is due in the middle of 2025. This is not a long time for such a transformation. The law is local, so different city governments can make changes before enacting their own versions. Businesses are already raising their voices—some support it and some complain about the costs and the exclusions. The law also extends to educational institutions and residential buildings.

My wife is the president of our co-op building and a strong environmentalist. Her immediate reaction to the law was, “OK, what do we do now?” This is almost the same question that I have raised in the context of the campuses: OK, we know what to do with new buildings—we simply tell the contractors to follow certain rules. But how do we tackle the problem of old buildings?

Let us start by analyzing the carbon emissions from a building—any building, old or new. Many publications, such as Energy Star’s Portfolio Manager, include instructions on how to do so. “Energy-related emissions” describes both direct and indirect forms. Both depend on the type of energy source that we are using. Direct emissions come from fossil fuels such as natural gas, gasoline, and oil. Indirect emissions include the fuels that our power companies are using to produce the electricity that we use. Any non-local power distribution (such as steam) should count as an indirect emission.

It is important for non-scientists to recognize that one can’t directly measure emissions. For direct emissions, one must use the “emission coefficients” that are published by organizations such as EIA (Energy Information Administration), which correlate the amounts of specific fuels that one uses with the standard emissions that result from burning these fuels. I use these coefficients to teach my students how to calculate emissions by using basic principles such as the chemistry of the fuels. Just type EIA into the search box at the top of the blog (click on the little magnifying glass) to see some examples. For indirect emissions, we need to find the fuel composition that our power company is using. My recent set of blogs about electric cars contains some of my best examples of this process (March 12, 19, 26, 2019). Next week’s blog will focus on electricity use.

The best way to save on energy-related emissions is obviously to use less energy. For this, we have to do an energy audit of a building, identify where the energy losses are, and try to minimize them. We can do this through better insulation, changing windows, using more efficient lightning, painting our roofs white or covering them with vegetation, and upgrading to better thermostats as well as energy certified refrigerators and air conditioners.

As usual, if you have the money and you don’t want to bother yourself with any of this, you can farm out the process. Most electric utilities now have the capacity to provide you with carbon-free electricity generated from renewable sources. You can now convert most of your energy use to electricity—this is not the most efficient or cost-effective method but you pay for convenience. It will cost you but as long as the electricity is being produced from renewable energy you will have no problem complying with the emissions mandate.

Below, I end this blog with the City’s two-page summary of the law, including a timeline with the new emissions requirements in NYC.

The Law: Summary of local law 97

Meanwhile, here are a few useful links:

Free NYC advisory on how to achieve these targets

NYC’s existing program for multifamily buildings