I am starting to write this blog on Thursday, June 20th, the Summer Solstice: the longest day of the year in the Northern Hemisphere. The concept of the “day after” has recently been widely used, mainly in the context of the Hamas-Israel war but also often when discussing the Russian invasion of Ukraine: what will happen when the war is over? These are not the only countries that are presently in some sort of state of war but they are the ones currently attracting the most global attention.

It seems that the “day after” is much more often discussed by people who cannot do anything about a situation rather than those who have the power to make big decisions. It should be useful to expand the concept to other important changes that we are experiencing. The global energy transition is high on my agenda, and the next few blogs will focus on the issue. In doing so, I will start by asking where we are in the transition, where we want to be after the transition is over, and what we are doing about it. The top picture summarizes the concept from my perspective. The photograph was taken from my balcony in NYC of a scene that lasted only a few seconds. The setting sun is the central element; it signifies that once we “finish” the energy transition, most of our energy the “day after” will be derived—whether directly or indirectly—from the sun’s present energy. This is an important distinction from fossil fuels, which are the remnants of millions of years of solar energy. The picture is full of dark clouds partially illuminated by the setting sun and both the clouds and the sun beautify NYC. I will repeat this photograph throughout this series unless I get bored and/or take a better one that illustrates my point.

This blog starts to address the important question of how the world is doing in its transition to non-polluting energy sources. Based on what we find, we will try to extrapolate the continuation scenario to some endpoints and define them as a “day after” scenario (see July 6 – July 20, 2021 blogs about business-as-usual scenarios). To address this issue, we need to look at three important components of the energy transition:

- Efficiency of energy use, defined as the amount of energy that we need to generate our global GDP

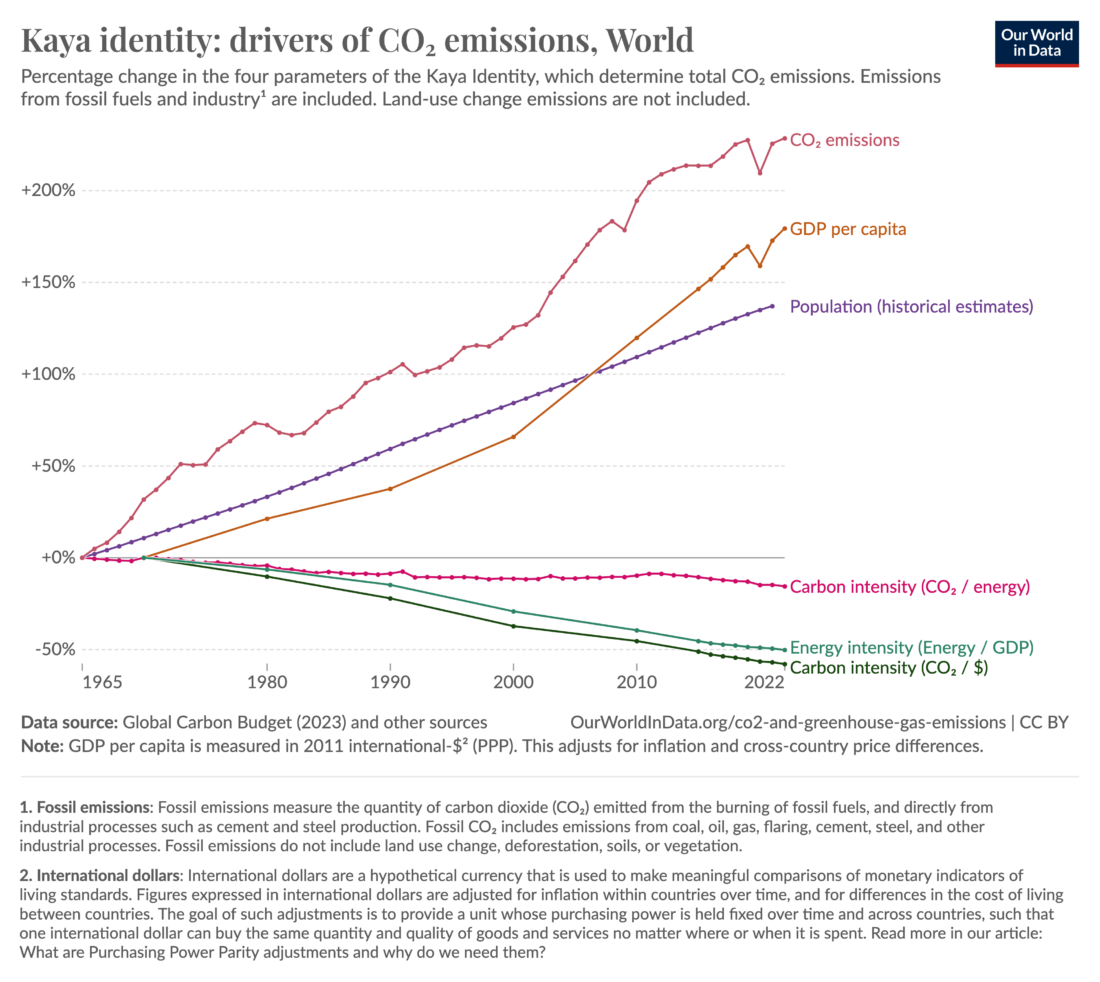

This term is defined by our global energy intensity. I addressed this issue in some detail in an earlier blog (December 20, 2022), where I showed the constant decline in this parameter (less energy needed for a given GDP) over the period of 1990 – 2015. The decline was global, applying to both developed and developing countries. Figure 2 below shows more recent data, with a continuing decline. The same figure also shows carbon intensity (put carbon intensity into the search box for background on the various aspects of the term) and population, among other metrics, all normalized from 1965. Both intensities (energy and carbon) are continuing to decline.

Figure 2 (Source: Our World in Data)

Figure 2 (Source: Our World in Data)

- Increase in the role of electricity in energy use

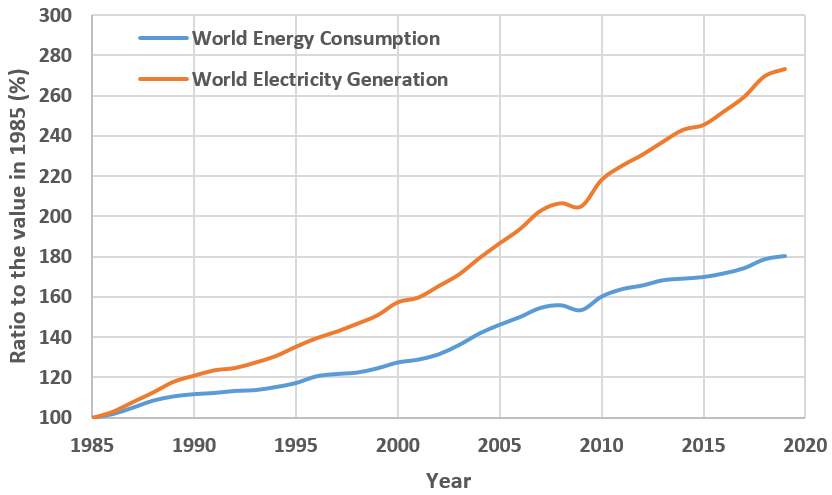

It was also demonstrated in previous blogs that the most flexible way to decarbonize our energy use is to convert most of our energy to electricity (see April 9 and 16, 2024 blogs). Figure 3 shows that an important consequence of the energy transition is the relatively sharper increase in electricity generation compared to the increase in overall energy use.

Figure 3 (Source: ResearchGate)

As was mentioned in this year’s April 9th blog, the recent jump in electricity demand is partially fueled by the recent developments in the use and production of electric cars and AI, both of which rely on electric power. Importantly, another significant part of the increased demand is the global increase in ability to use and generate electricity by countries that were not formerly able to participate in the transition (see April 16, 2024 blog).

But, as was discussed in earlier blogs (May 31, 2022), in most cases electricity is a secondary energy source. Converting energy sources to electricity contributes to the main objective of the energy transition only if the primary energy that is used for production is decarbonized.

- Decarbonizing Electricity

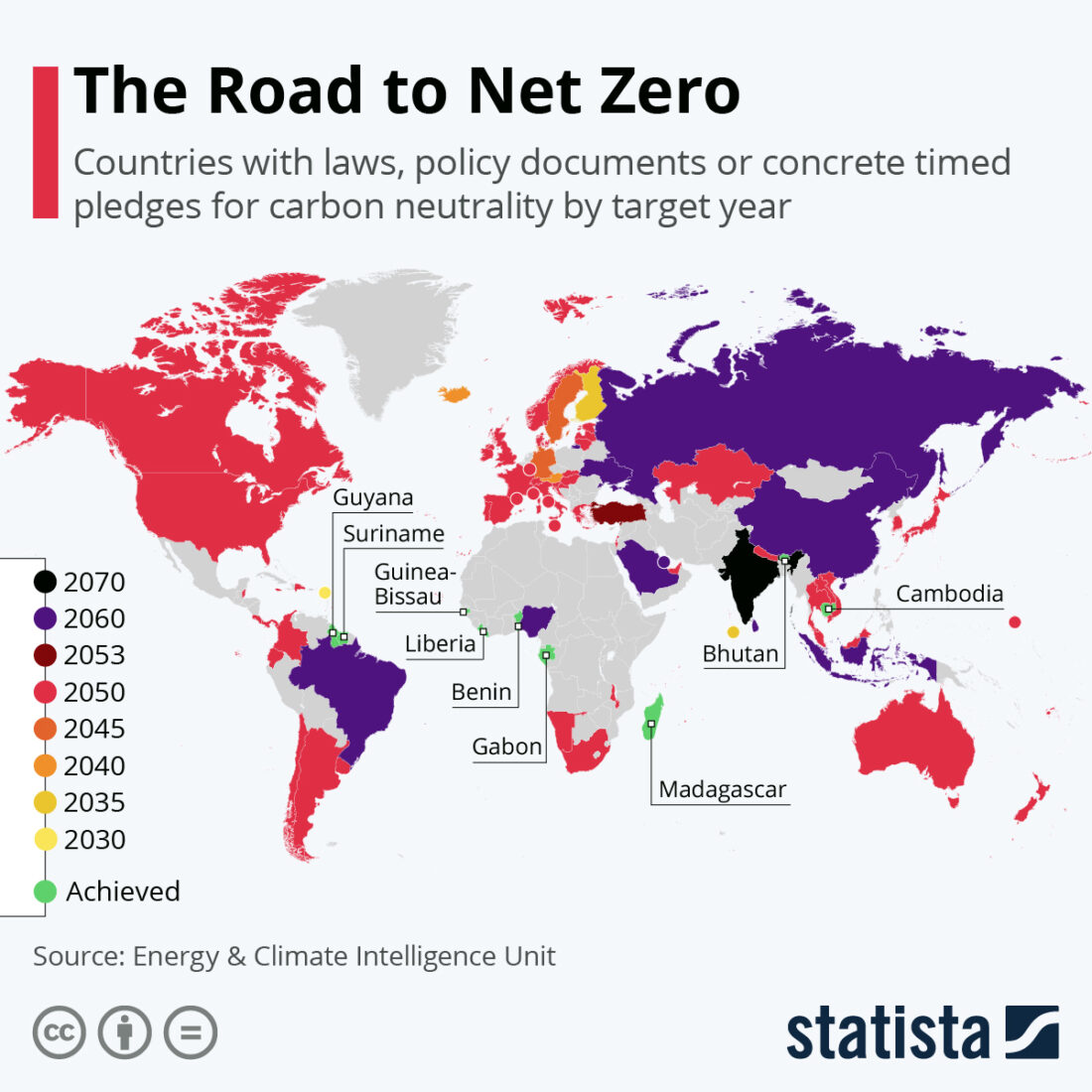

Many countries have made commitments to net-zero carbon in their electricity supply. Figure 4 shows these by date. This is much more helpful than the result of the Paris Agreement (See December 14, 2015 blog), which secured a commitment to a temperature increase with no specific date. However, as the situation in the US that followed the Paris Agreement showed, the validity of any such commitment is at the mercy of the state government.

The map shows a few small governments—mostly developing countries—that have already achieved the transition. However, the road to the “day after” here is clear: we can follow progress or regression.

Figure 4 – Countries with laws, policy documents, or concrete pledges for carbon neutrality by target year (Source: Statista)

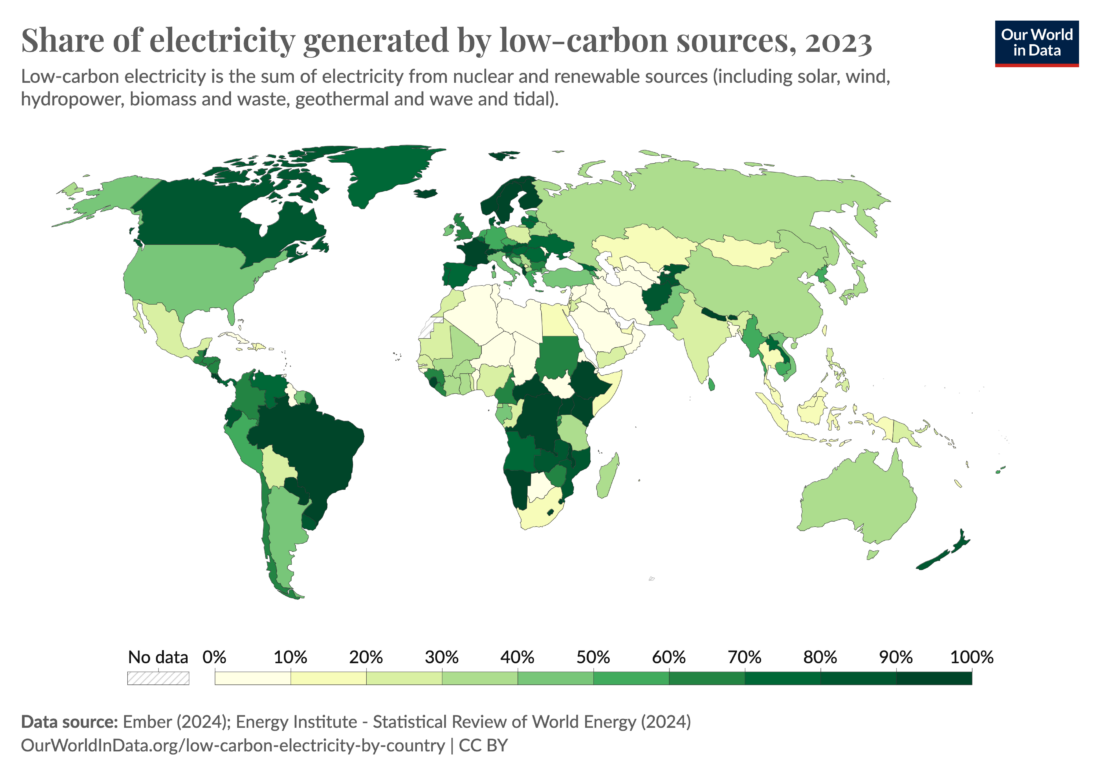

Figure 5 shows data for 2023 that tracks the success of non-fossil fuel energy around the world by share of electricity generated by low-carbon sources.

Figure 5 (Source: Our World In Data)

Next week’s blog will focus on the “day after,” when net-zero carbon will apply to all our energy use.