This is what remained of my family’s house in Warsaw after WWII. There is no longer any trace of it. I gave a brief summation of my early life when I wrote my first blog (April 22, 2012).

This is what remained of my family’s house in Warsaw after WWII. There is no longer any trace of it. I gave a brief summation of my early life when I wrote my first blog (April 22, 2012).

I was born in Warsaw, Poland in May, 1939. The first three years of my life were spent in the Warsaw Ghetto, as the Nazis developed their plans for systematic Jewish genocide. Before the destruction of the Ghetto in 1943, I was hidden for a time on the Aryan side by a family friend, but a Nazi “deal” to provide foreign papers to escape Poland resulted in my mother bringing me back to the Ghetto. Then a Nazi double-cross sent the remnants of my family not to safety in Palestine, but to the Bergen Belsen concentration camp as possible pawns in exchange for German prisoners of war. As the war was nearing an end, in April 1945, we were put on a train headed to Theresienstadt, a concentration camp further from the front lines. American tank commanders with the 743rd tank battalion of the American 30th Division intercepted our train near Magdeburg in Germany, liberating nearly 2500 prisoners. Within the year, my mother and I began building new lives in Palestine.

I am now a professor of Physics, studying the causes of global warming. I have just published a book on the topic: Climate Change: The Fork at the End of Now (June 2011 by Momentum Press). I publish literature regularly on climate change and energy, founded the Environmental Studies undergraduate program at Brooklyn College of CUNY, and have taught climate change on various levels for the last 15 years or so.

In addition, I speak three languages, Polish, Hebrew and English – a reflection of my immigration pattern, but I’d describe my knowledge of my birth language as “Kitchen Polish” as I never had any formal schooling in Poland.

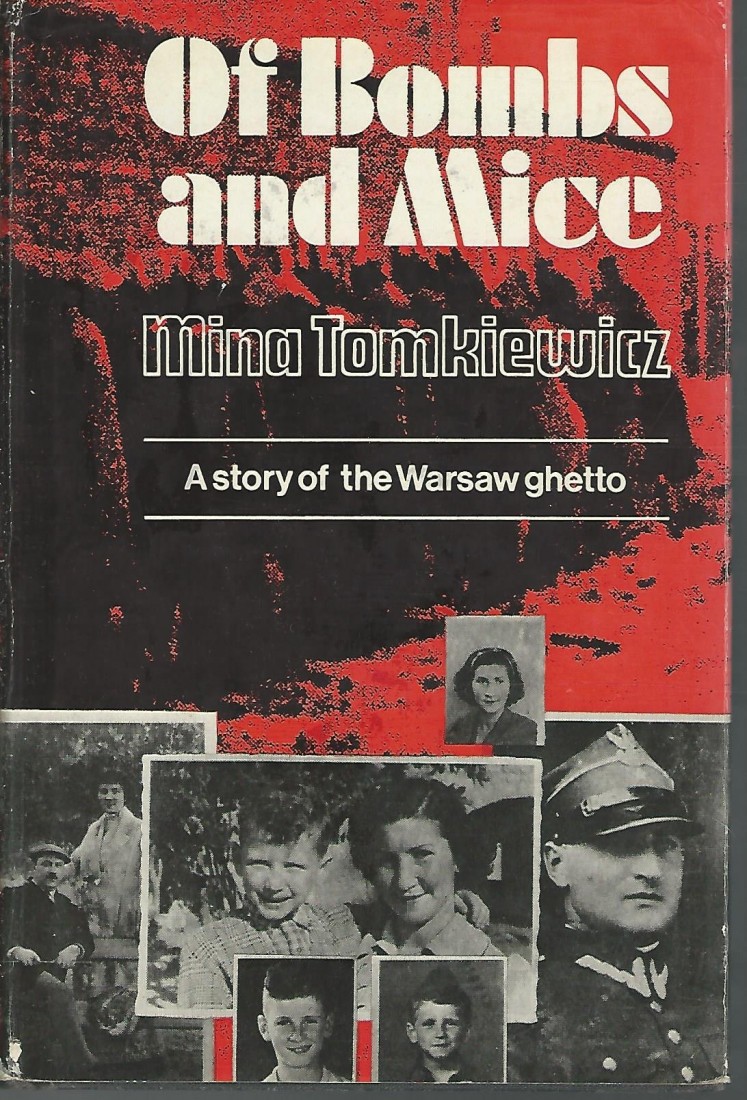

We spent the time between our liberation by the American Army and our emigration to Palestine (now Israel) in the displaced persons camp of Hillersleben. We were part of a mass exodus that took place as a result of the Holocaust. My mother’s book, Of Bombs and Mice, details our life in the Warsaw Ghetto during the first three years of my lifetime. Below is an excerpt describing the period directly after our liberation.

My mother’s book about the Warsaw Ghetto

My mother’s book about the Warsaw Ghetto

“My little angel, my sweetest baby in the World! Isn’t it fantastic that we are alive, so miraculously alive!” exclaimed Nata, showering wild kisses upon her six-year-old son Bobush. The naked, emaciated body of the blond boy eluded her grasp and Bobush ran away, his mischievous blue eyes set in a cherubic, pallid face, watching her intensely from a safe distance.

“I don’t want to be dressed, I want to go out now!” shouted Bobush, scratching himself all over with both dirty hands. Passing quickly from one mood to another, Nata started to weep. She cried hysterically: “you monster! You naughty boy! Come here at once or you’ll get a good spanking. If your father could have lived to see you now! Your poor grannie would…

She never finished the sentence, and after short fight with the struggling boy she managed to dress him, and herself, in the clothes she had found in the villa. Afterward she threw her own lice-infested clothes into the street, and they both went out to join the looting crowds.

The garden-town called Hillersleben, with its magnificently furnished houses, where-almost dying from starvation and disease-they had been transferred from the stinking, ghost-like train by the victorious Americans, had been the residential area for Hitler’s elite. The wide avenue, set in a frame of blooming trees, were in a state of riot now. Dressed in rags, looking for living skeletons, or horribly swollen, the liberated inmates of the concentration camps were wandering around, or wildly running through the thronged streets and flower-bedecked lawns, shouting, wildly waving their arms about, behaving without rhyme or reason. They invaded deserted villas and cellars well stocked by many prudent German Hausfrau, and they took everything in sight. From behind brightly-colored jam jars one could hear licking and swallowing noises and grunts of delight. Bizarre-looking figures were staggering under heavy suitcases full of loot and exchanging bewildered remarks.

“Who would have believed it yesterday? And so we have survived!”

I am Bobush and my mother is Nata.

I was an immigrant twice – once as a refugee. I was lucky because in both cases my country of choice actually wanted me. After the war, the Jewish Agency was looking for surviving Jewish families (especially those with children), to bring to Palestine to participate in the formation of Israel. I didn’t so much grow up in Israel as grow up with Israel. I went to two boarding schools designed to impart a mixture of standard education and agricultural work. Later, I served in the army, where I took part in one war and a number of skirmishes. I received my academic degrees and training at the Hebrew University and married another scholar. As many of our contemporaries were doing, we went to the US as postdoctoral fellows. Neither of us could find a job in Israel but we were both offered good professional opportunities in the US, so we stayed.

It is estimated that the European theatre of WWII displaced 6-8 million civilians. According to Mercy Corps, an international development agency that helps people survive after conflicts of all sorts, there are already 4 million Syrian refugees in 5 host countries. That number pales in comparison to the additional 16 million still in need of assistance throughout Syria and does not even begin to take into account the millions more refugees trying to escape from Iraq, Iran, Afghanistan, Yemen and various African countries. These people have not simply chosen to leave their home countries. They are fleeing violence and injustice, trying to make a life for themselves and their families.

Next week I will publish a guest blog by a first generation immigrant, a young Muslim student that has just graduated as the valedictorian of my university’s Honors College. She will describe her own set of experiences. Each of the millions that willingly leave or are forced to abandon their country, culture, and language, has a different story that emerges as part of the collective.