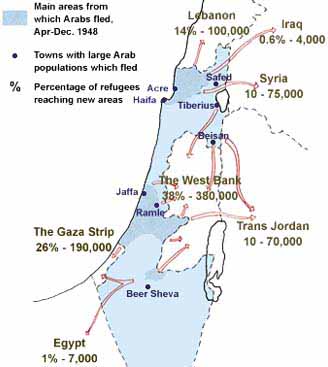

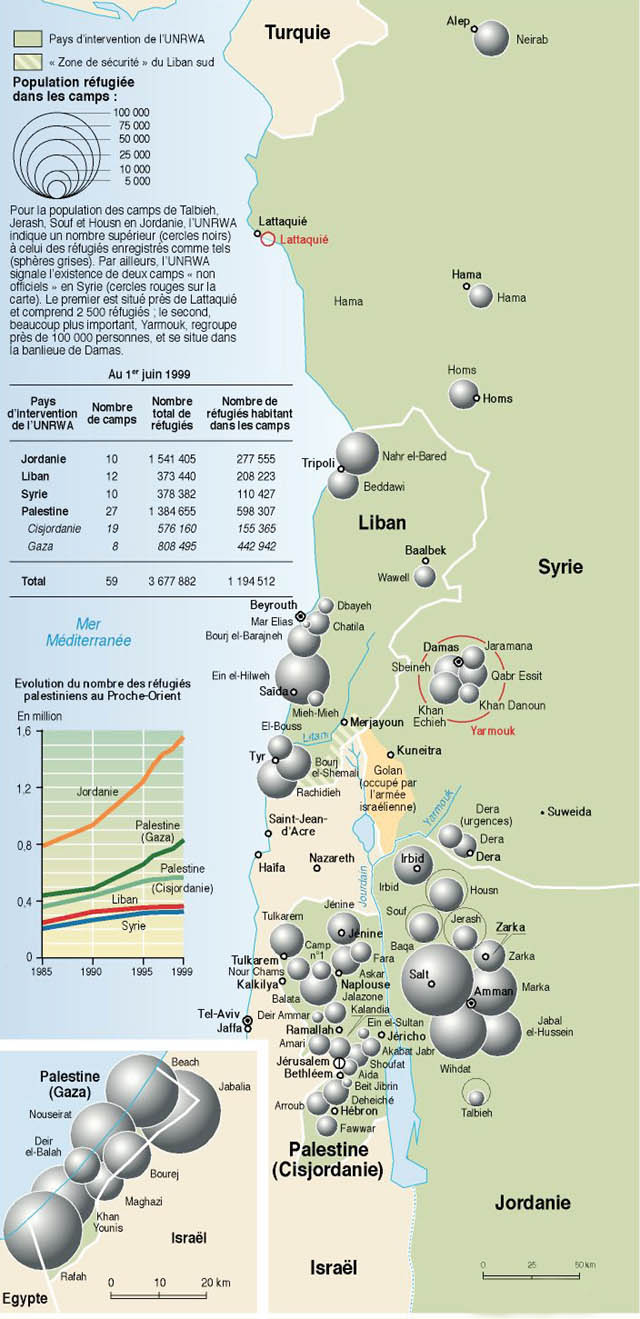

Figure 1 – A map of refugee camps in the Middle East

Figure 1 – A map of refugee camps in the Middle East

Successful resettlement is probably the most important aspect of the global refugee issue. Resettled refugees can make major positive contributions to their host societies. We have seen this happen globally throughout history (notably in both the US and Australia). The striking contrast between displaced and resettled refugees is especially apparent in the Middle East. More precisely, we have seen it pan out as a central, almost unsolvable problem within the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

As a Holocaust refugee, I was a resettled in Israel. At the time, it was part of Palestine, which was under British control. I grew up and got all of my education in Israel, as well as serving in the army. I hold dual Israeli-American citizenship and try to visit as often as possible. Even though I have issues with current government policies, I love the country and it was an important stopover in my vacation. Two of my elderly friends there, with whom I shared many aspects of the Holocaust experience, are in poor health so I wished to spend some time with them.

I also took the opportunity while I was in Israel to explore the issue of refugee resettlement and all that entails.

The Arab-Israeli conflict in 1948 dislocated Palestinian refugees from their homes and fundamentally decided their fate and prospects within the Middle East. It is a deeply disputed topic, to the point that is hard – if not impossible – to get an unbiased opinion about the discord. That very much includes my own views. The Syrian civil war, the Iraqi state’s disintegration, the rise of ISIS, and Yemen’s civil war have all worsened the magnitude of the Palestinian refugees’ plight.

I remember an incident highly relevant to this discussion: a few years ago, my school held a retreat for a few faculty members to discuss changes to the General Education program. I was already Director of the Environmental Studies program and sort of represented interdisciplinary educational efforts. During one of the meals, I sat near a history professor who specialized in the Middle East. He is a well know Jewish Arabist and is strongly left-leaning on the American political spectrum. I was teaching, then as now, Climate Change. Like many campuses, our student population is a mixture of strongly liberal students – many of them Jewish and an increasing numbers of them Muslim. I asked him how he teaches controversial topics like the Arab-Israeli conflict to such a mixture of backgrounds. He looked at me with a smiling face and responded that he relies heavily on original documents. I returned his smile to indicate that he might have been able to fool the students with that kind of methodology but his strategy didn’t fool me: he is the one who chooses the original documents; his biases are manifested by the documents that he selects.

For my part, I will start with Wikipedia’s descriptions of the Arab vs. Israeli points of view regarding the Palestinian refugees. I’ll continue with a Jewish website’s depiction of the two sides. Lastly, we’ll see a description of the Jewish exodus in the aftermath of the 1948 conflict and I will try to let you decide your own opinion without providing my own, biased take. To include the relevant paragraphs from these sources, the blog is going to be unusually long. My editor will be inclined to just cite the sources without posting the full excerpts. Doing so would mean the reader’s choices would shape the discussion, depending on which links they clicked or ignored. Instead, I want to curate the sources to include the full range. For this I need to quote them directly.

To start with, Wikipedia’s take on the two sides:

Israeli views [edit]

The Jewish Agency promised to the UN before 1948 that Palestinian Arabs would become full citizens of the State of Israel,[72] and the Israeli declaration of independence invited the Arab inhabitants of Israel to “full and equal citizenship”.[73] In practice, Israel does not grant citizenship to the refugees, as it does to those Arabs who continue to reside in its borders. The 1947 Partition Plan determined citizenship based on residency, such that Arabs and Jews residing in Palestine but not in Jerusalem would obtain citizenship in the state in which they are resident. Professor of Law at Boston University Susan Akram, Omar Barghouti and Ilan Pappé have argued that Palestinian refugees from the envisioned Jewish State were entitled to normal Israeli citizenship based on laws of state succession.[74]

Arab states [edit]

The Arab League has instructed its members to deny citizenship to original Palestine Arab refugees (or their descendants) “to avoid dissolution of their identity and protect their right to return to their homeland”.[75]

Tashbih Sayyed, a fellow of the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, criticized Arab nations of violating human rights and making the children and grandchildren of Palestinian refugees second class citizens in Lebanon, Syria, or the Gulf States, and said that the UNRWA Palestine refugees “cling to the illusion that defeating the Jews will restore their dignity”.[76]

Palestinian views [edit]

Palestine refugees claim a Palestinian right of return. In lack of an own country, their claim is based on Article 13 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), which declares that “Everyone has the right to leave any country including his own, and to return to his country”, although it has been argued that the term only applies to citizens or nationals of that country. Although all Arab League members at the time- Egypt, Iraq, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, Syria, and Yemen– voted against the resolution,[77] they also cite the non-binding article 11 of United Nations General Assembly Resolution 194, which “Resolves that the refugees wishing to return to their homes and live at peace with their neighbors should be permitted to do so at the earliest practicable date, and that compensation should be paid for the property of those choosing not to return […].”[71] However it is currently a matter of dispute whether Resolution 194 referred only to the estimated 50,000 remaining Palestine refugees from the 1948 Palestine War, or additionally to their UNRWA-registered 4,950,000 descendants. The Palestinian National Authority supports this claim, and has been prepared to negotiate its implementation at the various peace talks. Both Fatah and Hamas hold a strong position for a claimed right of return, with Fatah being prepared to give ground on the issue while Hamas is not.[78] However, a report in Lebanon’s Daily Star newspaper in which Abdullah Muhammad Ibrahim Abdullah, the Palestinian ambassador to Lebanon and the chairman of the Palestinian Legislative Council’s Political and Parliamentary Affairs committees,[79] said the proposed future Palestinian state would not be issuing Palestinian passports to UNRWA Palestine refugees – even refugees living in the West Bank and Gaza.

In a 2 January 2005 opinion poll conducted by the Palestinian Association for Human Rights involving Palestinian refugees in Lebanon:[80]

- 96% refused to give up their right of return

- 3% answered contrary

- 1% did not answer

The two sides as presented by the Jewish Virtual Library:

Israel’s Attitude Toward the Refugees

When plans for setting up a state were made in early 1948, Jewish leaders in Palestine expected the population to include a significant Arab population. From the Israeli perspective, the refugees had been given an opportunity to stay in their homes and be a part of the new state. Approximately 160,000 Arabs had chosen to do so. To repatriate those who had fled would be, in the words of Foreign Minister Moshe Sharett, “suicidal folly.”

Israel could not simply agree to allow all Palestinians to return, but consistently sought a solution to the refugee problem. Israel’s position was expressed by David BenGurion (August 1, 1948):

When the Arab states are ready to conclude a peace treaty with Israel this question will come up for constructive solution as part of the general settlement, and with due regard to our counterclaims in respect of the destruction of Jewish life and property, the long-term interest of the Jewish and Arab populations, the stability of the State of Israel and the durability of the basis of peace between it and its neighbors, the actual position and fate of the Jewish communities in the Arab countries, the responsibilities of the Arab governments for their war of aggression and their liability for reparation, will all be relevant in the question whether, to what extent, and under what conditions, the former Arab residents of the territory of Israel should be allowed to return.

The Israeli government was not indifferent to the plight of the refugees; an ordinance was passed creating a Custodian of Abandoned Property “to prevent unlawful occupation of empty houses and business premises, to administer ownerless property, and also to secure tilling of deserted fields, and save the crops….”

The implied danger of repatriation did not prevent Israel from allowing some refugees to return and offering to take back a substantial number as a condition for signing a peace treaty. In 1949, Israel offered to allow families that had been separated during the war to return; agreed to release refugee accounts frozen in Israeli banks (eventually released in 1953); offered to pay compensation for abandoned lands and, finally, agreed to repatriate 100,000 refugees.

The Arabs rejected all the Israeli compromises. They were unwilling to take any action that might be construed as recognition of Israel. They made repatriation a precondition for negotiations, something Israel rejected. The result was the confinement of the refugees in camps.

Despite the position taken by the Arab states, Israel did release the Arab refugees’ blocked bank accounts, which totaled more than $10 million. In addition, through 1975, the Israeli government paid to more than 11,000 claimants more than 23 million Israeli pounds in cash and granted more than 20,000 acres as alternative holdings. Payments were made by land value between 1948 and 1953, plus 6 percent for every year following the claim submission.

After the Six-Day War, Israel allowed some West Bank Arabs to return. In 1967, more than 9,000 families were reunited and, by 1971, Israel had readmitted 40,000 refugees. By contrast, in July 1968, Jordan prohibited persons intending to remain in the East Bank from emigrating from the West Bank and Gaza.

Arab Attitudes Toward the Refugees

The UN discussions on refugees had begun in the summer of 1948, before Israel had completed its military victory; consequently, the Arabs still believed they could win the war and allow the refugees to return triumphant. The Arab position was expressed by Emile Ghoury, the Secretary of the Arab Higher Committee:

It is inconceivable that the refugees should be sent back to their homes while they are occupied by the Jews, as the latter would hold them as hostages and maltreat them. The very proposal is an evasion of responsibility by those responsible. It will serve as a first step towards Arab recognition of the State of Israel and partition.

The Arabs demanded that the United Nations assert the “right” of the Palestinians to return to their homes, and were unwilling to accept anything less until after their defeat had become obvious. The Arabs then reinterpreted Resolution 194 as granting the refugees the absolute right of repatriation and have demanded that Israel accept this interpretation ever since.

One reason for maintaining this position was the conviction that the refugees could ultimately bring about Israel’s destruction, a sentiment expressed by Egyptian Foreign Minister Muhammad Salah al-Din:

It is well-known and understood that the Arabs, in demanding the return of the refugees to Palestine, mean their return as masters of the Homeland and not as slaves. With a greater clarity, they mean the liquidation of the State of Israel (Al-Misri, October 11, 1949).

After the 1948 war, Egypt controlled the Gaza Strip and its more than 200,000 inhabitants, but refused to allow the Palestinians into Egypt or permit them to move elsewhere.

Although demographic figures indicated ample room for settlement existed in Syria, Damascus refused to consider accepting any refugees, except those who might refuse repatriation. Syria also declined to resettle 85,000 refugees in 1952-54, though it had been offered international funds to pay for the project. Iraq was also expected to accept a large number of refugees, but proved unwilling. Lebanon insisted it had no room for the Palestinians. In 1950, the UN tried to resettle 150,000 refugees from Gaza in Libya, but was rebuffed by Egypt.

Jordan was the only Arab country to welcome the Palestinians and grant them citizenship (to this day Jordan is the only Arab country where Palestinians as a group can become citizens). King Abdullah considered the Palestinian Arabs and Jordanians one people. By 1950, he annexed the West Bank and forbade the use of the term Palestine in official documents.

In 1952, the UNRWA set up a fund of $200 million to provide homes and jobs for the refugees, but it went untouched.

The plight of the refugees remained unchanged after the Suez War. In fact, even the rhetoric stayed the same. In 1957, the Refugee Conference at Homs, Syria, passed a resolution stating:

Any discussion aimed at a solution of the Palestine problem which will not be based on ensuring the refugees’ right to annihilate Israel will be regarded as a desecration of the Arab people and an act of treason (Beirut al Massa, July 15, 1957).

The treatment of the refugees in the decade following their displacement was best summed up by a former UNRWA official, Sir Alexander Galloway, in April 1952: “The Arab States do not want to solve the refugee problem. They want to keep it as an open sore, as an affront to the United Nations and as a weapon against Israel. Arab leaders don’t give a damn whether the refugees live or die.”

Little has changed in succeeding years. Arab governments have frequently offered jobs, housing, land and other benefits to Arabs and non-Arabs, excluding Palestinians. For example, Saudi Arabia chose not to use unemployed Palestinian refugees to alleviate its labor shortage in the late 1970’s and early 1980’s. Instead, thousands of South Koreans and other Asians were recruited to fill jobs.

The situation grew even worse in the wake of the Gulf War. Kuwait, which employed large numbers of Palestinians but denied them citizenship, expelled more than 300,000 of them. “If people pose a security threat, as a sovereign country we have the right to exclude anyone we don’t want,” said Kuwaiti Ambassador to the United States, Saud Nasir Al-Sabah (Jerusalem Report, June 27, 1991). Most of whom were expelled settled in Jordan.

By the end of 2010, the number of Palestinian refugees on UNRWA rolls had risen to nearly 5 million, several times the number that left Palestine in 1948. In just the past three years, the number grew by 8 percent. Today, 42 percent of the refugees live in the territories; if you add those living in Jordan, 80 percent of the Palestinians currently live in “Palestine.” Though the popular image is of refugees in squalid camps, less than one-third of the Palestinians are in the 59 UNRWA-run camps.

During the years that Israel controlled the Gaza Strip, a consistent effort was made to get the Palestinians into permanent housing. The Palestinians opposed the idea because the frustrated and bitter inhabitants of the camps provided the various terrorist factions with their manpower. Moreover, the Arab states routinely pushed for the adoption of UN resolutions demanding that Israel desist from the removal of Palestinian refugees from camps in Gaza and the West Bank. They preferred to keep the Palestinians as symbols of Israeli “oppression.”

The Jewish Exodus (via Wikipedia):

The Jewish exodus from Arab and Muslim countries or Jewish exodus from Arab countries (Hebrew: יציאת יהודים ממדינות ערב, Yetziat yehudim mi-medinot Arav; Arabic: هجرة اليهود من الدول العربية والإسلامية hijrat al-yahūd min ad-duwal al-‘Arabīyah wal-Islāmīyah) was the departure, flight, expulsion, evacuation and migration, of 850,000 Jews,[1][2] primarily of Sephardi and Mizrahi background, from Arab and Muslim countries, mainly from 1948 to the early 1970s. They and their descendants make up the majority of Israeli Jews.

A number of small-scale Jewish exoduses began in many Middle Eastern countries early in the 20th century with the only substantial aliyah coming from Yemen and Syria.[3] Prior to the creation of Israel in 1948, approximately 800,000 Jews were living in lands that now make up the Arab world. Of these, just under two-thirds lived in the French and Italian-controlled North Africa, 15–20% in the Kingdom of Iraq, approximately 10% in the Kingdom of Egypt and approximately 7% in the Kingdom of Yemen. A further 200,000 lived in Pahlavi Iran and the Republic of Turkey.

The first large-scale exoduses took place in the late 1940s and early 1950s, primarily from Iraq, Yemen and Libya. In these cases over 90% of the Jewish population left, despite the necessity of leaving their property behind.[4] Two hundred and sixty thousand Jews from Arab countries immigrated to Israel between 1948 and 1951, accounting for 56% of the total immigration to the newly founded state.[5] Following the establishment of the State of Israel, a plan to accommodate 600,000 immigrants over four years, doubling the existing Jewish population, was submitted by the Israeli government to the Knesset.[6] The plan, however, encountered mixed reactions; there were those within the Jewish Agency and government who opposed promoting a large-scale emigration movement among Jews whose lives were not in danger.[6]

Later waves peaked at different times in different regions over the subsequent decades. The peak of the exodus from Egypt occurred in 1956 following the Suez Crisis. The exodus from the other North African Arab countries peaked in the 1960s. Lebanon was the only Arab country to see a temporary increase in its Jewish population during this period, due to an influx of Jews from other Arab countries, although by the mid-1970s the Jewish community of Lebanon had also dwindled. Six hundred thousand Jews from Arab and Muslim countries had reached Israel by 1972.[7][8][9][10] In total, of the 900,000 Jews who left Arab and other Muslim countries, 600,000 settled in the new state of Israel, and 300,000 immigrated to France and the United States. The descendants of the Jewish immigrants from the region, today known as Mizrahi Jews (“Eastern Jews”), currently constitute more than half of the total population of Israel,[11] partially as a result of their higher fertility rate.[12] In 2009, only 26,000 Jews remained in Arab countries and Iran[13] and 26,000 in Turkey.[14]

The reasons for the exodus included push factors, such as persecution, antisemitism, political instability,[15] poverty[15] and expulsion, together with pull factors, such as the desire to fulfill Zionist yearnings or find a better economic status and a secure home in Europe or the Americas. The history of the exodus has been politicized, given its proposed relevance to the historical narrative of the Arab-Israeli conflict.[16] When presenting the history, those who view the Jewish exodus as analogous to the 1948 Palestinian exodus generally emphasize the push factors and consider those who left as refugees, while those who do not, emphasize the pull factors and consider them willing immigrants.

Those who continue to suffer most throughout this conflict are the ones in the camps shown in Figure 1: generations succeeding generations without any hope in sight.