When I first became a professor, I taught chemistry and physics. Both are traditional sciences with well-defined prerequisites. For physics you must first learn about mechanics (Kepler, Newton, etc.); in chemistry you have to start with the periodic table before you can move forward. The speed and depth of a student’s progress depend strongly on their understanding of the fundamentals. Environmental science, meanwhile, requires a much broader background that expands beyond physical science. Social sciences—especially economics—play a very important role. When I started teaching about environmental issues, I had to change my approach. I find that ranking indicators—such as countries’ progress in sustainability—is a good starting place.

The fields of physics and chemistry change with time but at a relatively slow pace. They are also relegated to advanced classes in both undergraduate and K-12 curricula, meaning that they are not something most people think about. Environmental issues (the interactions between the physical world and human societies), meanwhile, change quickly and constantly and they affect us all. Policy changes have a relatively mild impact on physics and chemistry. The opposite is true for environmental issues, as we can see using environmental indexes.

The Environmental Performance Index (EPI) is a convenient example:

Careful measurement of environmental trends and progress provides a foundation for effective policymaking. The 2018 Environmental Performance Index (EPI) ranks 180 countries on 24 performance indicators across ten issue categories covering environmental health and ecosystem vitality. These metrics provide a gauge at a national scale of how close countries are to established environmental policy goals. The EPI thus offers a scorecard that highlights leaders and laggards in environmental performance, gives insight on best practices, and provides guidance for countries that aspire to be leaders in sustainability.

The first EPI index came out in 2002. It was designed to complement the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) (October 6, 2015 and March 3, 2020 blogs). Every two years, an updated EPI index is published.

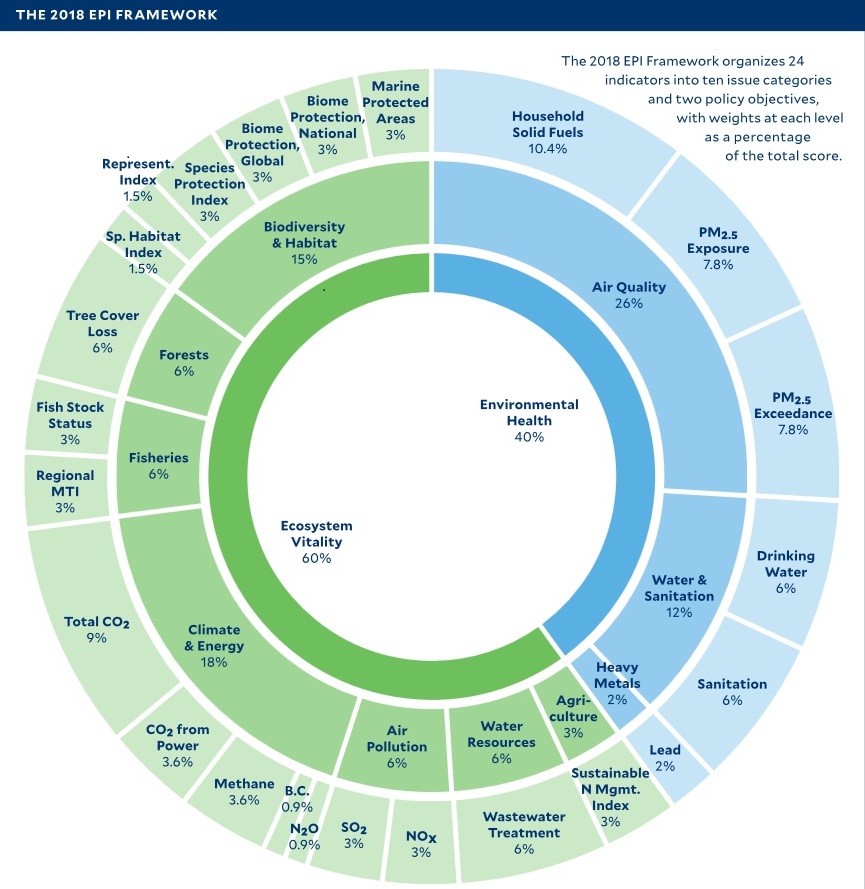

Figure 1 shows the indicators and their corresponding weight in the 2018 index.

Figure 1 – Environmental Performance Framework 2018

I used an earlier version of EPI’s Environmental Performance Framework in an honor class to demonstrate the methodology. It’s essentially a map of what goes into the EPI scoring. (Think of a grading system where one test is worth 30% of the grade, etc.) One can adjust the indicators and their weight (percentage of the whole) depending on what one values most. If we want to use such indexes to incentivize policy makers to improve on certain categories like the environment, we must first consider those policy makers’ priorities. Some of them, especially those in less developed, poorer countries, may give the most weight to immediate-term issues such as food and medical care. Unsurprisingly, such countries do not tend to consider long-term sustainability a high priority.

The indicators are divided into two main groups: ecosystem vitality and environmental health. Even on this level, the division is largely subjective and arbitrary. The two groups impact each other (November 27, 2018).

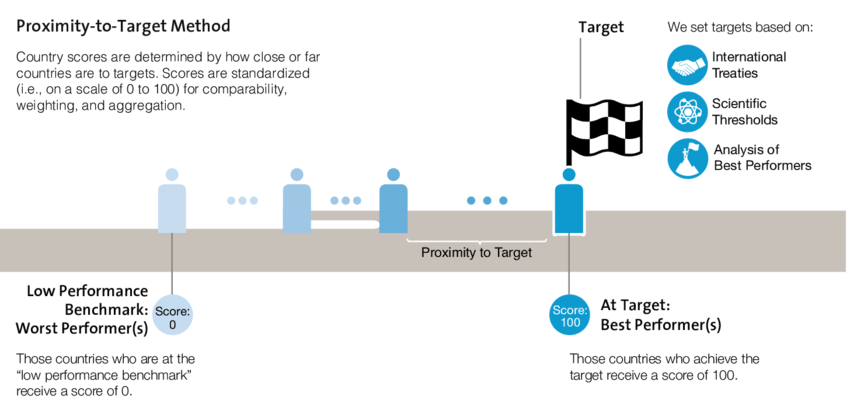

Figure 2 shows a schematic of how the EPI ranks countries: the Proximity to Target Method.

Figure 2– Proximity to Target Method of ranking

On a fundamental level, all indexes anchor on directly measurable indicators that are available via reputable databases (the outer circle in Figure 1). The subjective weights (given as a percentage in Figure 1) that we assign each category will determine how they move from the inner circuit to the outer circuits.

To make the indexing meaningful, it is essential to make sure that data are available for all the participants (in this case, countries) over the same time period.

Once direct data are available, we can scale them by putting the worst performer(s) as zero and the best performer as 100 and using the normalized data to get the overall index between 0 and 100, effectively ranking them. Alternatively, if we have targets for specific indicators from international treaties or scientific considerations, we can use those targets as the 100 markers.

Such indexing can influence more than just country-level policy makers. Schools and businesses are also subject to ranking but the datasets come from different sources.

For higher education institutions (see May 28, June 4, and June 18, 2019 blogs) the data are self-reported by campuses in response to a specific organization’s questions. The organization might analyze the information in-house or hand it over to an associated site, such as Sierra Club, which has a different set of priorities.

When the targets are companies, Bloomberg terminals can be tremendously helpful (January 8, 2019 blog). They include detailed information on ESG (Environmental, Social, and Government) indicators of various businesses, based on Thomson-Reuters scores. You can find more details here.

As an exercise, I often have students select 10 countries and rank them according to their own priorities, using the Proximity to Target technique. I challenge you to do the same. Make sure that you provide the reference for the data on which your ranking is based and post it as a comment on this blog.