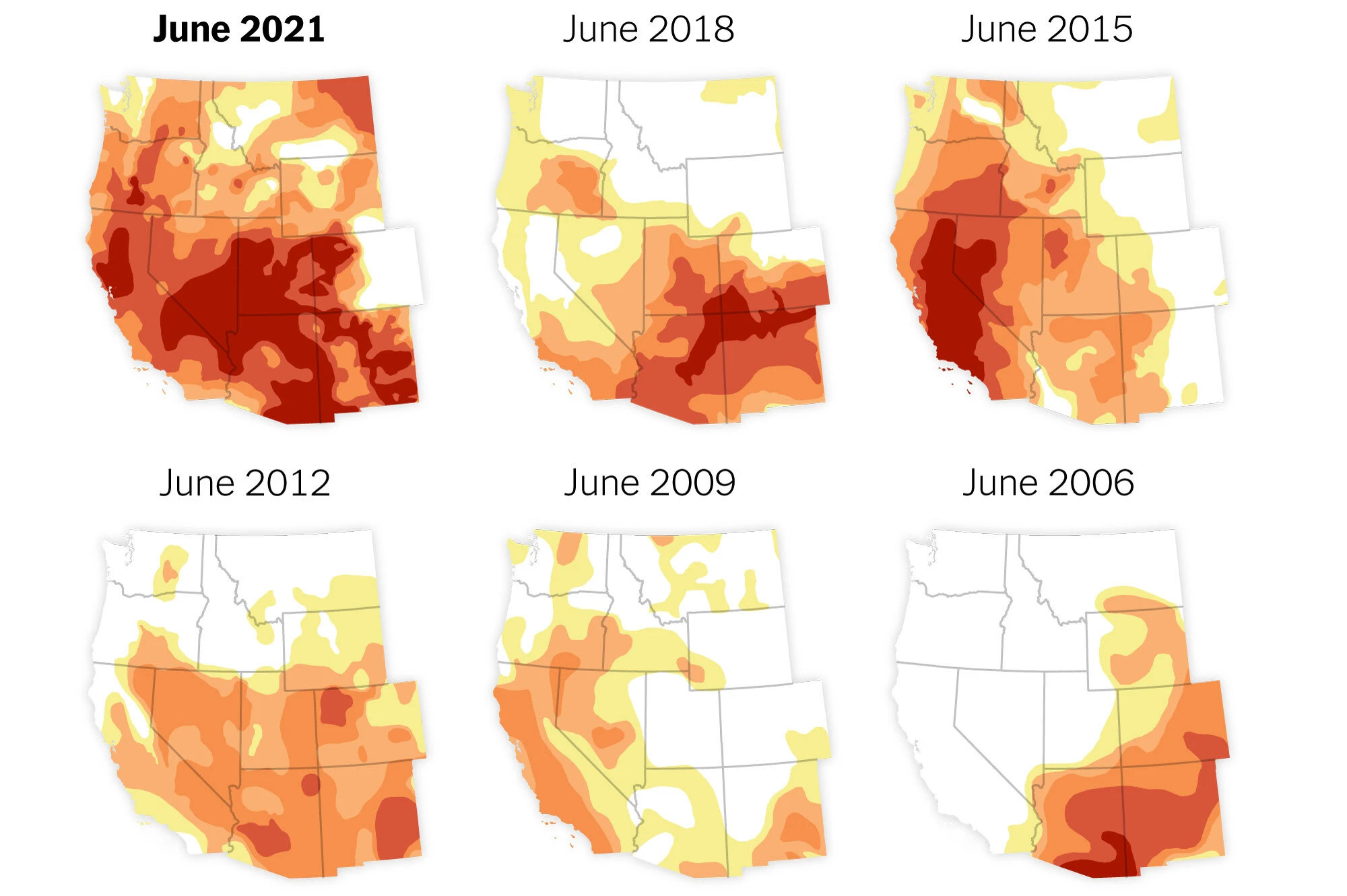

Summer has officially started. Over the last week or so, I’ve been keeping track of which large US cities have experienced temperatures above 100oF, according to the New York Times weather report (see August 18, 2020 blog for descriptions of these reports). American cities that have consistently shown temperatures above 110oF include Las Vegas, Phoenix, and Tucson, all of which are in the Southwest. A few other areas across the country, most shockingly in the Pacific Northwest, have been fluctuating between 100o – 110oF. These extreme conditions regularly cause severe droughts, water shortages, and fires. The press has been covering the matter in depth:

Sonya Landau, who edits this blog and wrote last week’s guest post, lives in Tucson, Arizona. She was kind enough to share an account of some of the consequences of this intense heat. All of this serves as an urgent reminder that we are already feeling the effects of climate change and we have to do something about it—not in the future but now. The Paris agreement, which we have just rejoined, set an objective to limit human-caused climate change to no more than 1.5oC (2.7oF) above pre-industrial conditions by 2050. A recent report by the International Energy Agency (IEA) laid out a roadmap to achieve this objective. The IEA is probably the most qualified global agency to analyze our global energy use and its likely consequences:

The International Energy Agency (IEA; French: Agence internationale de l’énergie) is a Paris-based autonomous intergovernmental organisation established in the framework of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in 1974 in the wake of the 1973 oil crisis.[1] The IEA was initially dedicated to responding to physical disruptions in the supply of oil, as well as serving as an information source on statistics about the international oil market and other energy sectors. It is best known for the publication of its annual World Energy Outlook.[2]

In the decades since, its role has expanded to cover the entire global energy system, encompassing traditional energy sources such as oil, gas, and coal as well as cleaner and faster growing ones such as solar PV, wind power and biofuels. As the Covid-19 pandemic set off a global health and economic crisis in early 2020, the IEA called on governments to ensure that their economic recovery plans focus on clean energy investments in order to create the conditions for a sustainable recovery and long-term structural decline in carbon emissions.[3]

Today the IEA acts as a policy adviser to its member states, as well as major emerging economies such as Brazil, China, India, Indonesia and South Africa to support energy security and advance the clean energy transition worldwide. The Agency’s mandate has broadened to focus on providing analysis, data, policy recommendations and solutions to help countries ensure secure, affordable and sustainable energy for all. In particular, it has focused on supporting global efforts to accelerate the clean energy transition and mitigate climate change. The IEA has a broad role in promoting rational energy policies and multinational energy technology co-operation with a view to reaching net zero emissions.[4]

The IEA’s current Executive Director is Fatih Birol, who took office in late 2015 and began his second term four years later.

In response to the growing number of pledges by countries and companies around the world to limit their emissions to net zero by 2050 or soon after, although that is not compatible with the 1.5 °C target, that would require net zero in the mid 2030’s, IEA announced in January 2021 that it would produce a roadmap for the global energy sector to reach 2050 net zero. The IEA says the report, due to be published on May 18, 2021, tries to map out a pathway in line with preventing global temperatures from rising above 1.5 °C – something that environmental groups, investors and companies had been urging the IEA to do.[5] All IEA member countries have signed the Paris Agreement which strives to limit warming to 1.5 °C and two thirds of IEA member governments have made commitments to emission neutrality in 2050.

The agency’s official site has descriptions of its energy-related reports.

Last month, the IEA posted a new report, “Net-Zero by 2050 – a Roadmap for Global Energy Sector.” I found this report to be so important that I have decided to dedicate the second half of both my courses next semester to the topic.

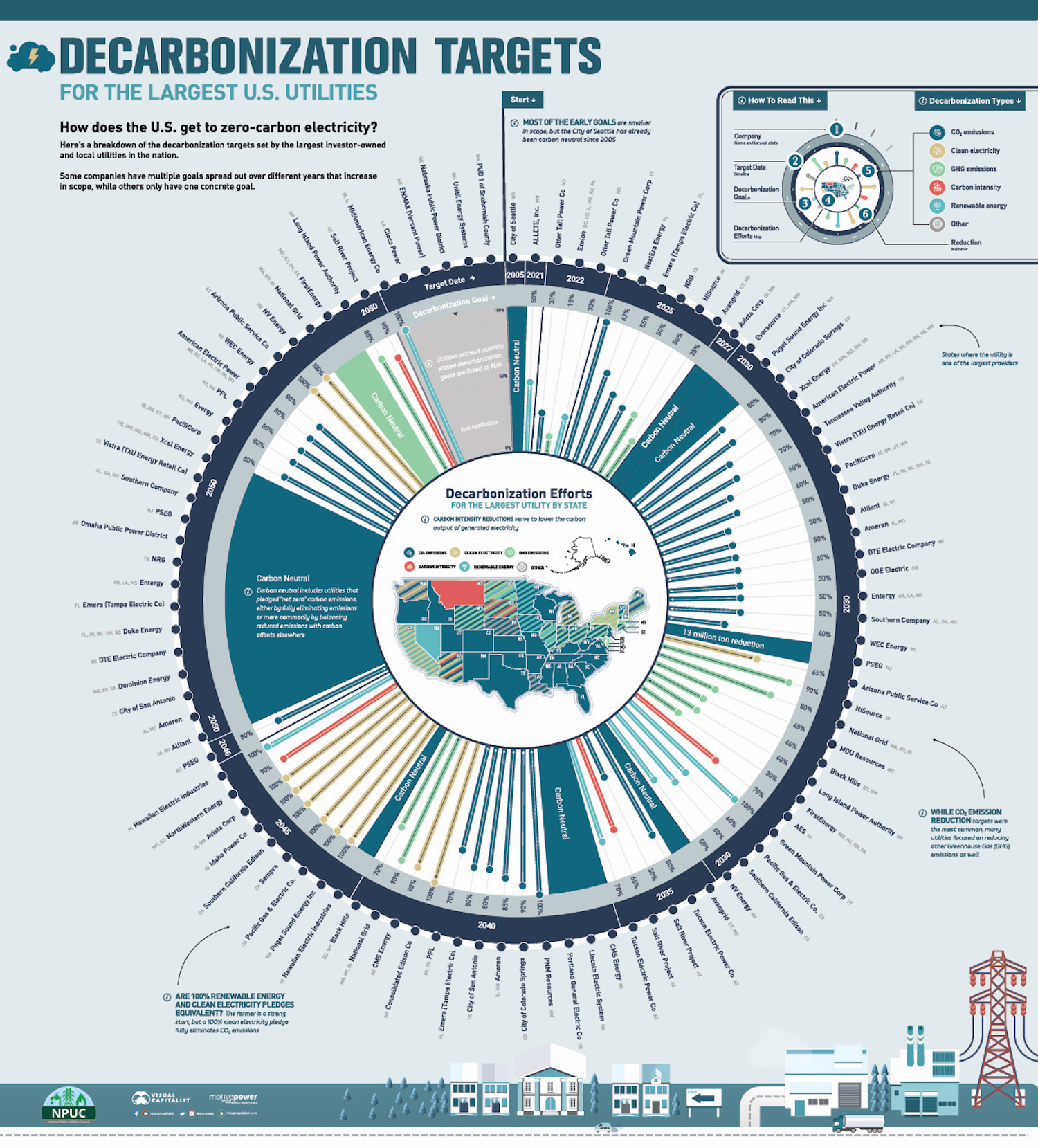

I took the opening figure for this blog, “Decarbonization Targets for the largest US Utilities,” from the Visual Capitalist site. It is very much in keeping with the spirit of the IEA’s official report. I admire this site’s climate change-related graphics and have shared them here before (see the 2021 blogs on January 5th, March 30th, and April 6th). They do a great job at illustrating massive amounts of data in a way that is more accessible to non-scientists but the resulting graphics can be very large and crowded. The one at the top of this blog is a good example. Don’t worry if you cannot read everything; the original copy on their site lets you enlarge the figure to your liking. The figure demonstrates the current progress on decarbonizing the most important component of the needed energy transition: electrical utilities.

The IEA report is long (224 pages), with impressive graphics of its own. The agency’s press release describes its focus:

The world has a viable pathway to building a global energy sector with net-zero emissions in 2050, but it is narrow and requires an unprecedented transformation of how energy is produced, transported and used globally, the International Energy Agency said in a landmark special report released today.

Climate pledges by governments to date – even if fully achieved – would fall well short of what is required to bring global energy-related carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions to net zero by 2050 and give the world an even chance of limiting the global temperature rise to 1.5 °C, according to the new report, Net Zero by 2050: a Roadmap for the Global Energy Sector.

The report is the world’s first comprehensive study of how to transition to a net zero energy system by 2050 while ensuring stable and affordable energy supplies, providing universal energy access, and enabling robust economic growth. It sets out a cost-effective and economically productive pathway, resulting in a clean, dynamic and resilient energy economy dominated by renewables like solar and wind instead of fossil fuels. The report also examines key uncertainties, such as the roles of bioenergy, carbon capture and behavioural changes in reaching net zero.

“Our Roadmap shows the priority actions that are needed today to ensure the opportunity of net-zero emissions by 2050 – narrow but still achievable – is not lost. The scale and speed of the efforts demanded by this critical and formidable goal – our best chance of tackling climate change and limiting global warming to 1.5 °C – make this perhaps the greatest challenge humankind has ever faced,” said Fatih Birol, the IEA Executive Director. “The IEA’s pathway to this brighter future brings a historic surge in clean energy investment that creates millions of new jobs and lifts global economic growth. Moving the world onto that pathway requires strong and credible policy actions from governments, underpinned by much greater international cooperation.”

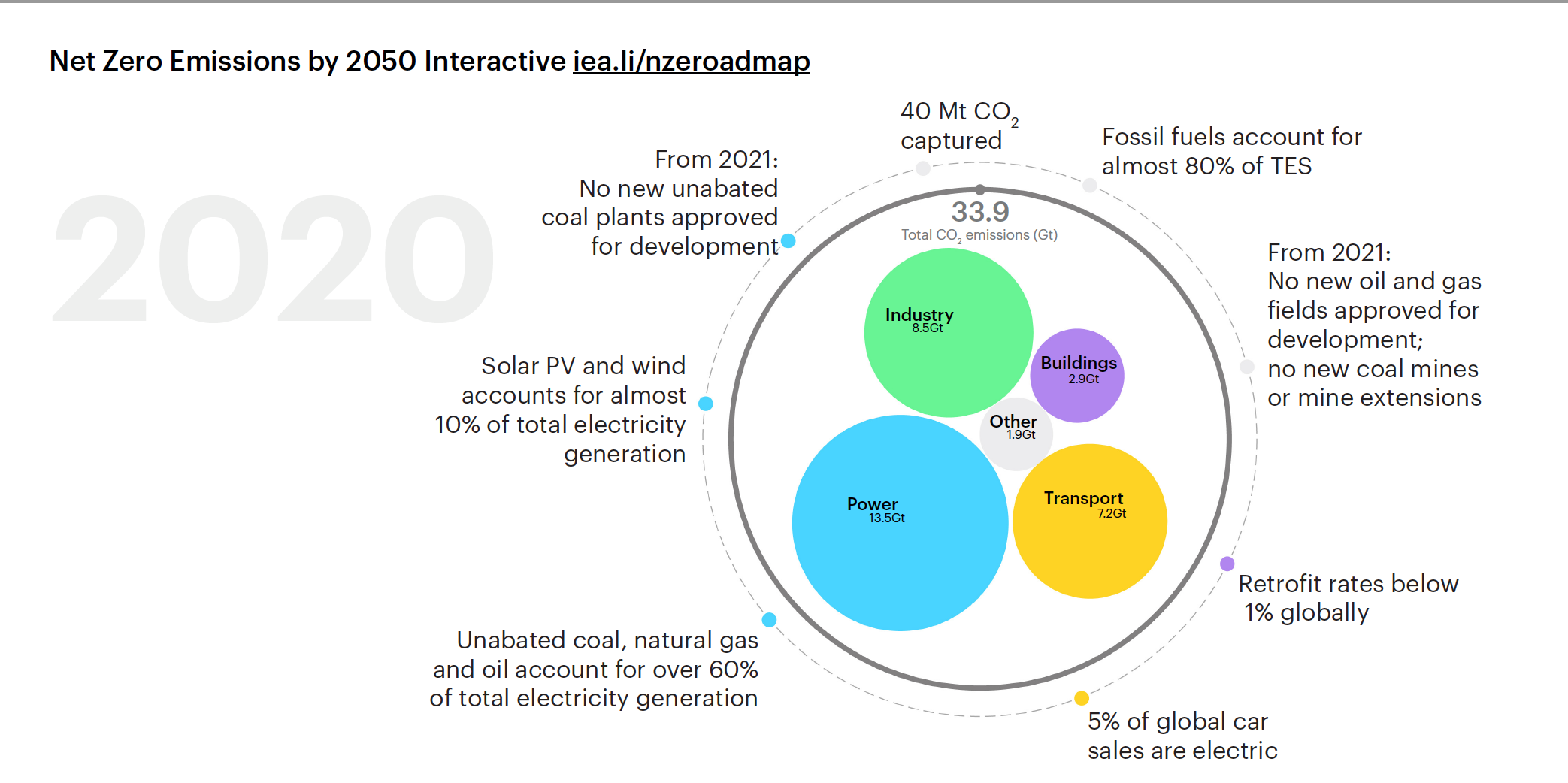

Figure 1 shows the present situation. Every five years, when the IEA releases a report, it includes figures similar to the one below, judged against the 2050 net-zero deadline.

Figure 1 – Where we stand now: promises as of 2021

For clarity, the interior circles show the individual contributions to the total CO2 emissions:

Blue: Power – 13.5 Gt (G stands for billion)

Green: Industry – 8.5Gt

Yellow: Transportation – 7.2Gt

Violet: Buildings – 2.9Gt

White: Other – 1.9Gt

The total comes to the equivalent of 33.9 billion tons of carbon dioxide.

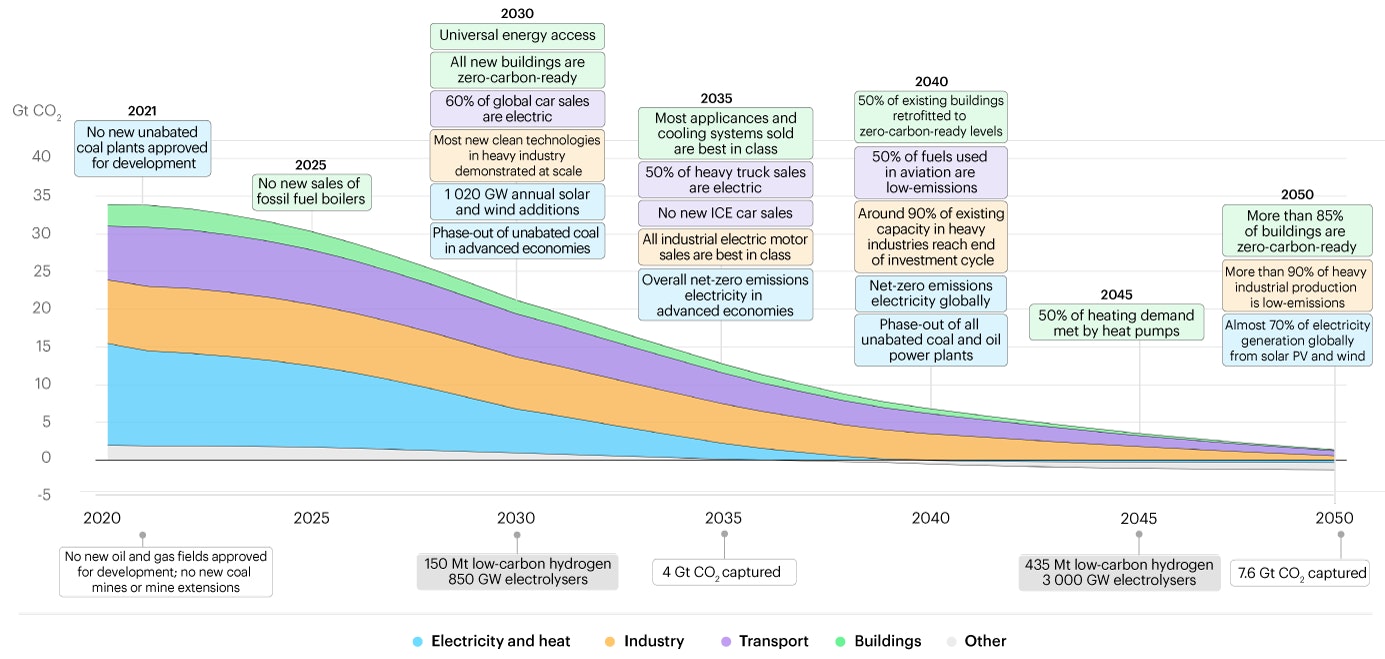

Figure 2 shows the proposed dynamics for the rest of the first half of the 21st century.

Figure 2 – Key milestones on the pathway to net zero

In the near future, I will turn my focus to the roles that energy companies and governments can/should play in the energy transition, as well as the importance of timing. I have discussed all of these topics numerous times in the more than 9 years since I began this blog but they require much sharper focus now that the IEA has published its newest report. I will also try to better define the concept of a business-as-usual scenario to illustrate the consequences if we fail to follow our commitments to drive carbon emissions down to zero by mid-century. As always, I want to stress that this is already a problem and we have to start working on adaptation and mitigation now.