I am not the only one to predict (February 3, 2015 and October 3, 2017) that continuing our practices in a business as usual scenario will lead to destruction of the physical environment as we know it – as well as what has already been labeled the sixth mass extinction. This extinction will not occur suddenly as the result of one event such as a nuclear war or collision with a large astronomical object; it will happen more gradually. Numerous visible markers strongly suggest that this process is already taking place.

Anthropogenic climate change fueled by the uncontrolled release of greenhouse gases is one of the main mechanisms leading us in that direction. Many now recognize the dangers and the world is trying to take steps to mitigate this process. One of the biggest steps is the transition toward non-carbon-based energy sources that do not change the energy balance of the planet. This should help keep us within the “Goldilocks Zone” – the ideal temperature and abundance of liquid water on the planet’s surface to support life. By all accounts, the transition is a stuttering one (December 24, 2012 blog and more recent entries) because of conflicts between future and present needs. My last few blogs tried to summarize where the most populated countries and the world as a whole stand in this process.

As in any case, people in more vulnerable situations and environments are trying to move to more stable ones. Such moves create major global security issues.

The US intelligence community recognizes the challenge and is required to publish periodic reports on the global situation (every 4 years) warning of some of the challenges. From the January 2017 report, “Global Trends: Paradox in Progress” (May 23, 2017):

Changing climate conditions challenged the capacity of many governments to cope, especially in the Middle East and Africa, where extended droughts reduced food and water supplies and high temperatures suppressed the ability of people to work outdoors. Large numbers of displaced persons from the region often found they had no place to go as a series of dramatic terrorist attacks in Western countries drove those governments to adopt stringent security policies that restricted immigration.

The US intelligence community also issues yearly reports of its observations about climate change and its recommendations for addressing the aspects that directly affect US security. Here are some excerpts from the beginning of the most recent report:

The Center for Climate & Security: Exploring The Security Risks of Climate Change

Program Areas

-

Policy Development: Convening and facilitating public-private collaborative policy development processes and dialogues in critical areas of the climate-security field, such as the role of national and intergovernmental security institutions in addressing climate change.

-

Analysis: Elevating the climate and security discourse through the Center for Climate and Security blog, our reports on the sub-national, national, regional and international security implications of climate change, and other publications.

-

Research: Conducting research to fill information gaps, including assessing the security community’s strategic and operational rationale for addressing climate change risks, examining the role of climate change, water and food insecurity in the security dynamics of strategically-significant regions of the world, and forecasting the potential of disruptive technologies to address climate and security risks.

-

Resource Hub: Answering frequently asked questions, keeping track of the latest policy developments, and acting as a resource hub for key climate and security documents from governments, international institutions, non-governmental organizations and academia.

Context

Climate change, in both scale and potential impact, is a strategically-significant security risk that will affect our most basic resources, from food to water to energy. National and international security communities, including militaries and intelligence agencies, understand these risks, and have already taken meaningful actions to address them. However, progress in comprehensively preventing, preparing for, adapting to and mitigating these risks will require that policy-makers, thought leaders and publics take them seriously.

Other countries have their own perspectives on the dangers they face:

Water, Conflict and Cooperation: Lesson From the Nile River Basin

by Patricia Kameri-Mbote:

In 1979, Egyptian President Anwar Sadat said: “The only matter that could take Egypt to war again is water.” In 1988 then-Egyptian Foreign Minister Boutros Boutros-Ghali, who later became the United Nations’ Secretary-General, predicted that the next war in the Middle East would be fought over the waters of the Nile, not politics. Rather than accept these frightening predictions, we must examine them within the context of the Nile River basin and the relationships forged among the states that share its waters.

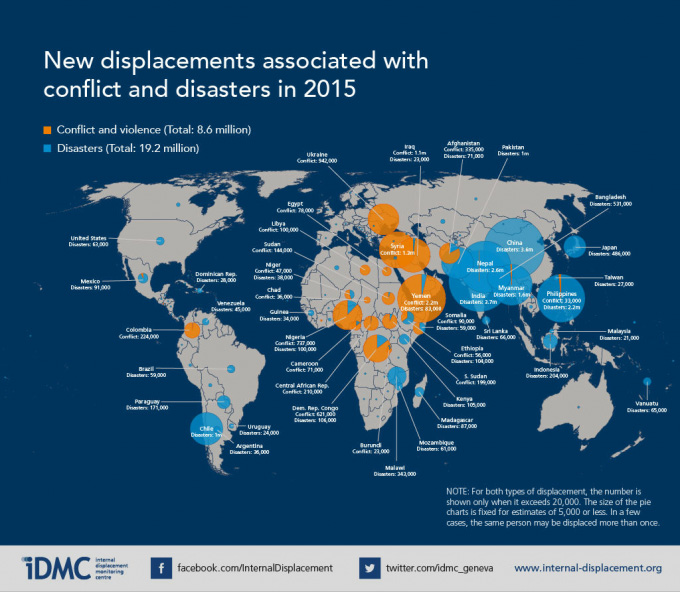

The iDMC (Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre) report addresses the vast number of displaced persons, an issue that is not relegated to the future but clearly visible now. Figure 1 shows a global picture of displacement:

Figure 1 confirms that displacements associated with disasters have surpassed those driven by conflicts and violence.

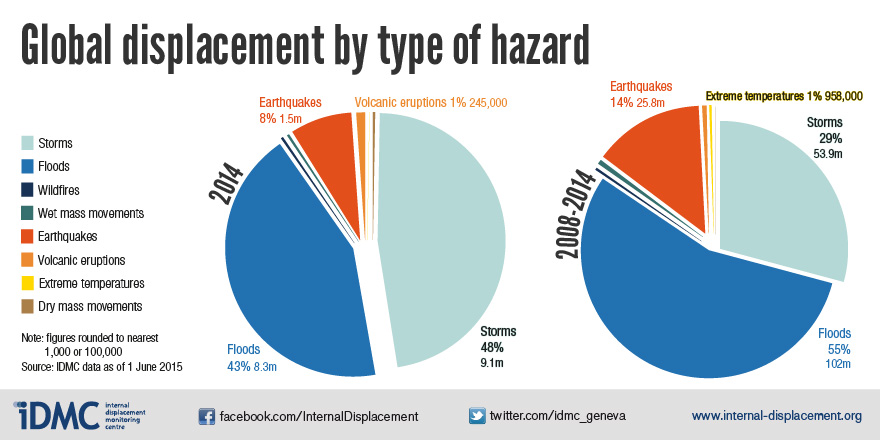

Figure 2 specifies the kinds of disasters in question.

Earthquakes and volcanic eruptions are not associated with anthropogenic climate change. The rest of the disasters are directly associated with climate change and our disturbance of the water cycle. These disasters are expected to worsen and spread as the global temperature rises, leading to even more displacement:

Climate refugees or environmental migrants are people who are forced to leave their home region due to sudden or long-term changes to their local environment. These are changes which compromise their well-being or secure livelihood. Such changes are held to include increased droughts, desertification, sea level rise, and disruption of seasonal weather patterns (i.e. monsoons[1]). Climate refugees may choose flee to or migrate to another country, or they may migrate internally within their own country.[2]

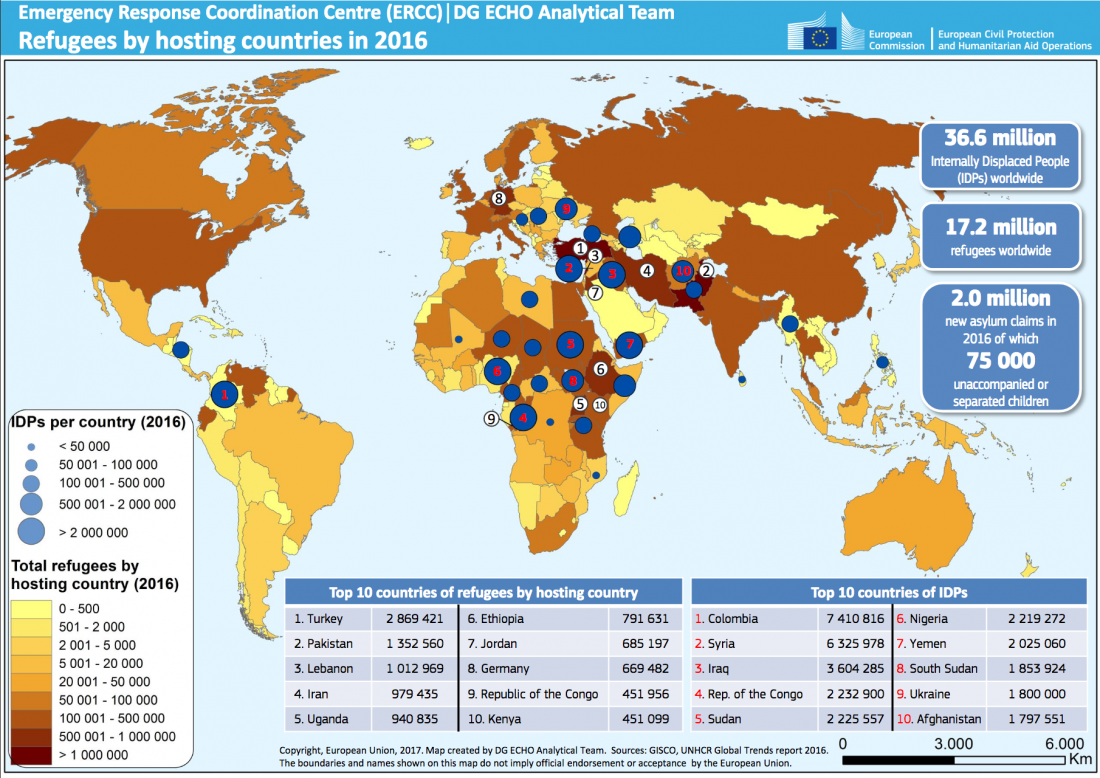

Figure 3 highlights the destination countries for displaced persons.

Figure 3 – Refugees by hosting countries in 2016

Figure 3 – Refugees by hosting countries in 2016

A large number of displaced persons do not leave their countries. When storms and sea level rise drive them from their homes, land, and livelihoods, they flock to cities in search of some relief and the hope of new opportunities. Here is an example from Bangladesh:

Cities Swell with Climate Migrants: Bangladesh’s capital Dhaka is struggling to absorb migrants from the countryside forced to move by environmental change, Part 3 of a special series.

By Lisa Friedman on March 16, 2009

Nearly 500,000 people – about the population of Washington, D.C. – move to this city on the banks of the Buriganga River each year, mostly from coastal and rural areas. More than 12 million people live in Dhaka, twice as many as just a decade ago. It’s one of the world’s most densely populated countries on a planet that is seeing rapid urbanization.

In Dhaka, migration experts say, climate change already is fueling urban arrivals. Coastal flooding is occurring with more frequency. Rice crops, in particular, are slowly dying because of creeping salinity levels, and in the worst cases, entire homes and villages are lost to fearsome storms.

A typical individual story:

Standing among the mazes of corrugated metal shacks with no running water or sanitation services, Omar said he left the town of Sherpur, north of Dhaka, “to earn a living.” He came from a family of farmers, but when floods ruined the crops in his village last year, he borrowed 500 taka (about $7) to take the bus to Dhaka.

Now he, his wife and their two daughters live in a single room and share a flimsy wooden plank latrine with about 35 other families in the Karail slum, across the river from Dhaka’s upper-class Gulshan neighborhood. He isn’t likely to go back to Sherpur.

“I don’t have the means to go home. I don’t have a house or anything over there. It’s not possible,” he said.

Next week I will return to the 17 countries that I have examined in recent blogs.

There certainly IS evidence regarding global w2arming and climate change! Just consider what has happened over the past decade or two: hurricane Katrina, other hurricanes along the Eastern coast, El Ninos and La Ninas, droughts in the U.S. west and Midwest, mudslides in California, huge forest fires out west, tornado activity in tornado alley and even one here in Brooklyn a few years ago during the night. I can go on and on! While one can argue that these natural disasters are not new and have happened through history, they did not seem to happen with such frequency and such force that often in the past! Global warming adds kinetic energy to the atmosphere and kinetic energy does not usually “sit still”!

One thing we might try to do in a changing world climate, at least to insure adequate food supplies, is to experiment with more genetic engineering of crops and food animals to make them more resistant to climate change. Examples might be crops that tolerate heat better, colder temperatures better, drier environments (less precipitation), wetter environments (more precipitation), wind and storm resistance, longer and shorter growing seasons etc. This might help mitigate the effects of climate change.