The alarming tone of the new IPCC report caught the immediate attention of the world’s media and triggered a quick dismissal from the president of the United States. The report, which spans about 1,300 pages, covers all the indicators that constitute early signs of the impending damage to the Earth. It emphasizes the amplification of damage expected between a global warming of 1.5oC and one of 2oC or higher. Since both temperatures are now becoming more and more questionable as achievable targets by the end of the century, the report also calls for a sharp acceleration in global efforts to completely decarbonize the world’s energy supply within one generation. This notion is an anathema to the current government of the US, the largest per-capita major global carbon emitter. But none of this came as a surprise to anyone who has been following the topic.

One big surprise (to me at least) was that the report finally included the concept of the Anthropocene. What’s more, it is featured at the very beginning of Chapter 1. This addition, in my opinion, is so significant and got such little media attention that I have decided to include it below despite repeated, “Do Not Cite, Quote or Distribute” warnings in the report:

Box 1.1: The Anthropocene: Strengthening the global response to 1.5°C global warming

Introduction

The concept of the Anthropocene can be linked to the aspiration of the Paris Agreement. The abundant empirical evidence of the unprecedented rate and global scale of impact of human influence on the Earth System (Steffen et al., 2016; Waters et al., 2016) has led many scientists to call for an acknowledgement that the Earth has entered a new geological epoch: the Anthropocene (Crutzen and Stoermer, 2000; Crutzen, 2002; Gradstein et al., 2012). Although rates of change in the Anthropocene are necessarily assessed over much shorter periods than those used to calculate long-term baseline rates of change, and therefore present challenges for direct comparison, they are nevertheless striking. The rise in global CO2 concentration since 2000 is about 20 ppm/decade, which is up to 10 times faster than any sustained rise in CO2 during the past 800,000 years (Lüthi et al., 2008; Bereiter et al., 2015). AR5 found that the last geological epoch with similar atmospheric CO2 concentration was the Pliocene, 3.3 to 3.0 Ma (Masson-Delmotte et al., 2013). Since 1970 the global average temperature has been rising at a rate of 1.7°C per century, compared to a long-term decline over the past 7,000 years at a baseline rate of 0.01°C per century (NOAA 2016, Marcott et al. 2013). These global-level rates of human-driven change far exceed the rates of change driven by geophysical or biosphere forces that have altered the Earth System trajectory in the past (e.g., Summerhayes 2015; Foster et al. 2017); even abrupt geophysical events do not approach current rates of human-driven change.

The geological dimension of the Anthropocene and 1.5°C global warming

The process of formalizing the Anthropocene is on-going (Zalasiewicz et al., 2017), but a strong majority of the Anthropocene Working Group (AWG) established by the Sub–Committee on Quaternary Stratigraphy of the International Commission on Stratigraphy have agreed that: (i) the Anthropocene has a geological merit; (ii) it should follow the Holocene as a formal epoch in the Geological Time Scale; and, that (iii) its onset should be defined as the mid–20th century. Potential markers in the stratigraphic record include an array of novel manufactured materials of human origin, and “these combined signals render the Anthropocene stratigraphically distinct from the Holocene and earlier epochs” (Waters et al., 2016). The Holocene period, which itself was formally adopted in 1885 by geological science community, began 11,700 years ago with a more stable warm climate providing for emergence of human civilization and growing human-nature interactions that have expanded to give rise to the Anthropocene (Waters et al., 2016).

The Anthropocene and the Challenge of a 1.5° C warmer world

The Anthropocene can be employed as a “boundary concept” (Brondizio et al., 2016) that frames critical insights into understanding the drivers, dynamics and specific challenges in responding to the ambition of keeping global temperature well below 2°C while pursuing efforts towards and adapting to a 1.5°C warmer world. The UNFCCC and its Paris Accord recognize the ability of humans to influence geophysical planetary processes (Chapter 2, Cross-Chapter Box 1 in this Chapter). The Anthropocene offers a structured understanding of the culmination of past and present human– environmental relations and provides an opportunity to better visualize the future to minimize pitfalls (Pattberg and Zelli, 2016; Delanty and Mota, 2017), while acknowledging the differentiated responsibility and opportunity to limit global warming and invest in prospects for climate-resilient sustainable development (Harrington, 2016) (Chapter 5). The Anthropocene also provides an opportunity to raise questions regarding the regional differences, social inequities and uneven capacities and drivers of global social–environmental changes, which in turn inform the search for solutions as explored in Chapter 4 of this report (Biermann et al., 2016). It links uneven influences of human actions on planetary functions to an uneven distribution of impacts (assessed in Chapter 3) as 29 well as the responsibility and response capacity to for example, limiting global warming to no more than a 1.5°C rise above pre–industrial levels. Efforts to curtail greenhouse gas emissions without incorporating the intrinsic interconnectivity and disparities associated with the Anthropocene world may themselves negatively affect the development ambitions of some regions more than others and negate sustainable development efforts (see Chapter 2 and Chapter 5).

I have frequently discussed the concept of the Anthropocene here (see February 3, 2015 blog, “Extinctions in the Anthropocene” and type Anthropocene into the search box for later entries). The IPCC report (Zalasiewicz et al., 2017) refers to a key publication in the journal Anthropocene ( 19, 55 (2017)) written by 25 participants in the AWG (Anthropocene Working Group) effort. However, the IPCC report does not include these crucial bits of the conclusion of the paper’s abstract:

Among the array of proxies that might be used as a primary marker, anthropogenic radionuclides associated with nuclear arms testing are the most promising; potential secondary markers include plastic, carbon isotope patterns and industrial fly ash. All these proxies have excellent global or near-global correlation potential in a wide variety of sedimentary bodies, both marine and non-marine.

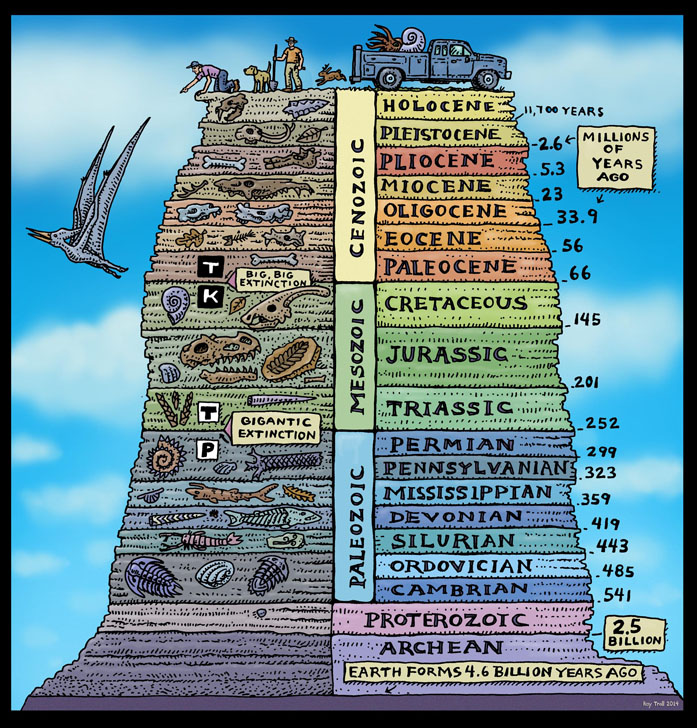

The time scale shown above illustrates geological epochs – most of which last for millions of years. The latest epoch, the Holocene, has lasted approximately 10,000 years (11,700 years in the IPCC report) and spans the approximate history of human civilization (agriculture, urban settlements, etc.). There is no precedence for declaring the “beginning” of a new epoch. As the IPCC report mentioned, the Holocene designation wasn’t approved until 1885. Fuller accounts reveal that the period was only submitted to the International Geological Congress at that time. It was endorsed by the US Commission on Stratigraphic Nomenclature (the same organization that is now considering the Anthropocene) in 1969 but it is still not universally accepted.

The suggestion mentioned in the IPCC report for a “boundary concept” is interesting but a boundary requires the definition of both sides – which we lack here. A much more appropriate measure is to declare an end of the Holocene – an action for which we have plenty of precedence in our mapping of the geological time scale.

The requirements for visible markers for the transition (the current geological epoch map is based on fossil and rock evidence) are logical; it is therefore appropriate that we use the anthropogenic radionuclides associated with nuclear arms testing from the middle of the last century as our guide. In the next blog I will discuss some of the markers for the Holocene and show that the primary marker for the Anthropocene can be traced to July 16, 1945 at the Trinity site in New Mexico – the very first test of nuclear weapons.

The AWG’s long gestation for this change (as of 2009) is nothing compared to that regarding the start of the Holocene – which as I mentioned, is still ongoing. Such a lag is understandable. It is a monumental job. The IPCC’s decision to acknowledge the period is welcome. Unless someone successfully claims ownership of the word “Anthropocene,” (suggested originally by Paul Crutzen and ecologist Eugene Stoermer, 2000), it is a useful term to adopt to describe the era in which anthropogenic actions are responsible for deteriorations in the physical environment that are likely to lead to uninhabitability.

Data show that the difference in atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide between the current reference (Industrial Revolution) and the end of WWII (1945) is small. The current reference is 280 ppmv while the 1945 concentration is recorded to have 310 ppmv. Shifting the reference to 1945 might remove some direct blame from industry and shift it instead to society’s inability to include environmental impact in its choice of tools to accelerate economic growth. Shifting the reference might also emphasize the culpability of a significant segment of the population (including myself) and encourage them/us to work a bit harder to make amends.

To conclude, there are two Anthropocenes: One is a full, official geological epoch that might last for thousands of years and requires markers that will only be observable throughout such a period; the other only requires recognition that the current epoch of the Holocene has to end to reflect humanity’s vast effects on the physical environment. Next week’s blog will expand on the latter.