I posted early last week so I could emphasize the importance of voting to my students before Tuesday’s election. As of today, some states are still counting votes and some are proceeding to recounts because of the narrow margins. The available results indicate that Republicans have maintained control of the Senate, increasing their majority by one senator. Meanwhile, Democrats gained control of the House of Representatives, flipping 30+ House seats. They also netted about seven new governorships, even though the majority of the races featured Democrats trying to keep their seats in “red” states. The few climate change resolutions that made it onto ballots didn’t get voters’ approval. It was clearly not an overwhelming victory for either party, which just underscores how split this country still is.

I posted early last week so I could emphasize the importance of voting to my students before Tuesday’s election. As of today, some states are still counting votes and some are proceeding to recounts because of the narrow margins. The available results indicate that Republicans have maintained control of the Senate, increasing their majority by one senator. Meanwhile, Democrats gained control of the House of Representatives, flipping 30+ House seats. They also netted about seven new governorships, even though the majority of the races featured Democrats trying to keep their seats in “red” states. The few climate change resolutions that made it onto ballots didn’t get voters’ approval. It was clearly not an overwhelming victory for either party, which just underscores how split this country still is.

A recent estimate put the number of eligible registered voters in the US north of 235 million. Current estimates of how many actually voted on Tuesday stand at roughly 114 million, which is below 50%. This means that yet again, more than 100 million eligible Americans decided that the issues were not important enough and it was OK to skip the voting booths. At Monday’s class before the election, I asked my students to bring their “I voted” stickers to the next class and promised to bring my own. I went to vote after work around 6pm. The media was already describing very heavy turnout with long lines at many polling locations so I was anticipating some waiting. There was none. However, after I voted, I went to claim my sticker. I didn’t get it. I was a bit upset and asked around, telling my local election staff about my promise to my students. They said that they’d run out, but after some pleading and intensive searching, a staff member was able to find me one to bring with me to class. Many of my students had similar experiences; instead, some of them took pictures of the stickers as a “receipt.” I viewed the shortage of stickers as evidence of a large turnout. Once the numbers started to come out, however, it was obvious that the turnout was only large relative to recent midterm elections – not nearly as high as presidential elections and not even close to the possible full participation. We still have work to do.

Well, what do these elections say about America, and what is the near-term prognosis? My view is that the Founding Fathers were near geniuses in that they were able to draft a document that can still serve as an example to the world of how governing states should work.

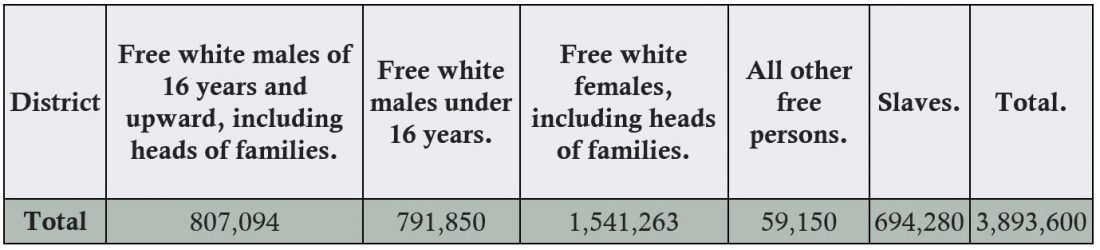

Our election process comes almost straight from the US Constitution, which was drafted in 1787 and ratified in 1790. As it happens, the first American census took place the same year. Table 1 summarizes the results:

Table 1 – Population data in the US compiled on the first census (1790)

The population now (2017) is 326 million with no slaves. We are the third most populous country in the world and the richest one. We are still bound by the same document from 1790 and it works just fine.

The population now (2017) is 326 million with no slaves. We are the third most populous country in the world and the richest one. We are still bound by the same document from 1790 and it works just fine.

Not everybody is happy with its enforcement, though. This unhappiness is especially loud when the popular vote delivers one message and the election’s result reflects another, as happened this time with the Senate vote and in the 2016 presidential election. Paul Krugman just wrote a sobering op-ed in the NYT: “Real America Versus Senate America: Some of us are more equal than others, and they like Trump.” The Constitution was written for a federation of states and needed to be ratified by three quarters of them (Article 5). Yet it has kept America stable for all of these years as the country grew (not counting “minor” events like the American Civil War).

Let’s use Congress as an example. House seats are allocated by population and we vote on their control in rounds every two years. If we are not happy with our congressperson, or with the party that he/she represents, we vote them out in the next election. Two years of being unhappy is not too long to manage. Congresspeople are elected to represent the people. Senators are elected to represent the land (i.e. the states). The distribution of people and land changes with time but the governing system is designed to keep the balance. Presidential elections also try to keep the balance between people and land, with overwhelming weight thrown behind the people (Electoral College).

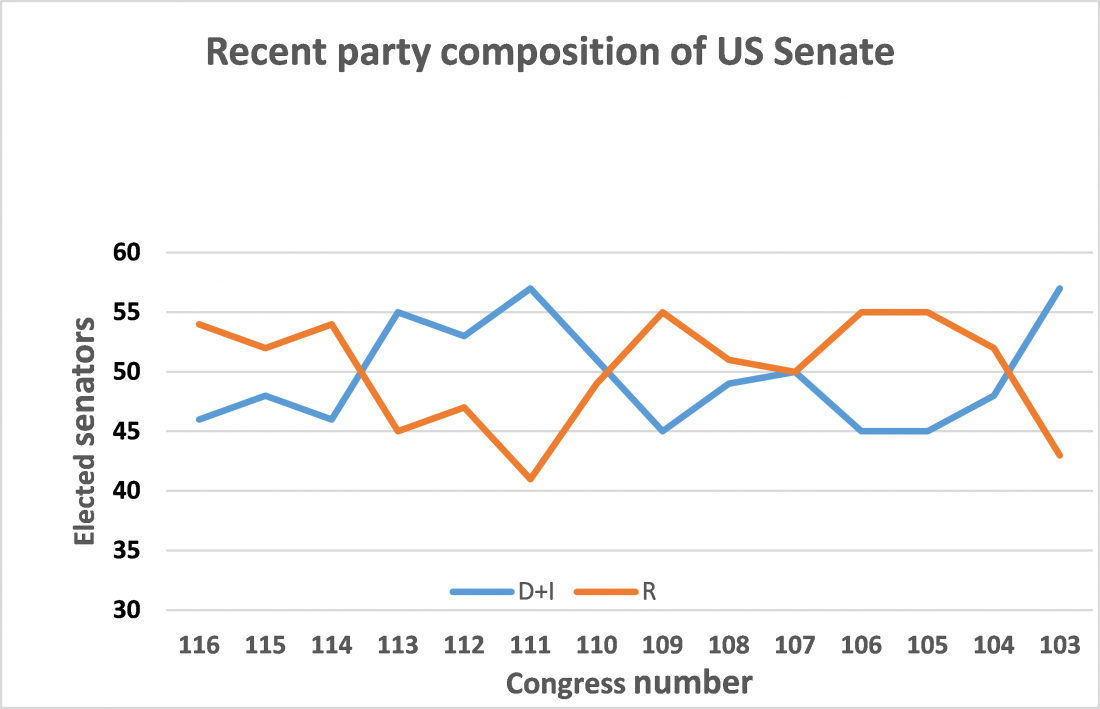

(Data taken from https://history.house.gov/Institution/Election-Statistics/Election-Statistics/) Markers for some of the congresses: 103 – 1993-1995; 116 – 2019-2021. As mentioned before, the data for the 116th Congress Senate elections are not final. In the 111th Congress, two positions remained vacant.

Figure 1 – Party composition of the US Senate in the last 12 Congresses

Each congressional election covers one third of the senatorial seats. The senators that stood for reelection in 2018 were last elected in 2012 (the 113th Congress), when the Senate was overwhelmingly controlled by Democrats, so naturally most of the senators that were up for reelection were Democrats. The party affiliation of their last – 112th – congressional election is shown in Figure 1 (keep in mind that we’re reading the graph from right to left here). One can see that this system has “memory.”

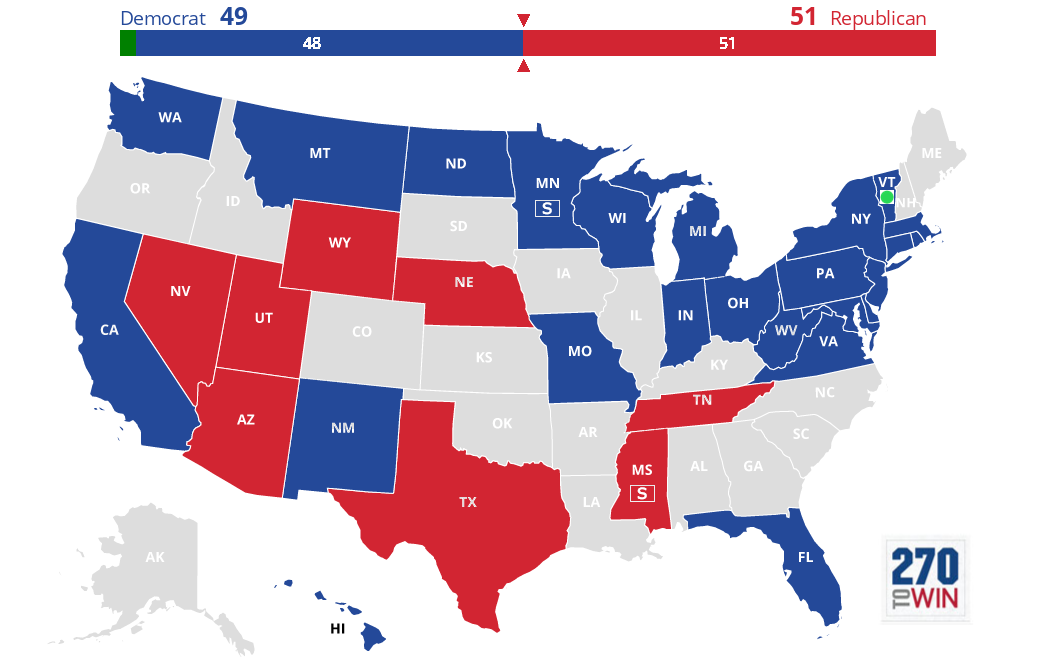

The electoral map of these senators is shown in Figure 2. Many of the Democratic senators who were up for reelection represent states that are now considered solidly “red” because they usually vote Republican. This time around, Democratic senators from Indiana, Missouri, and North Dakota lost their seats.

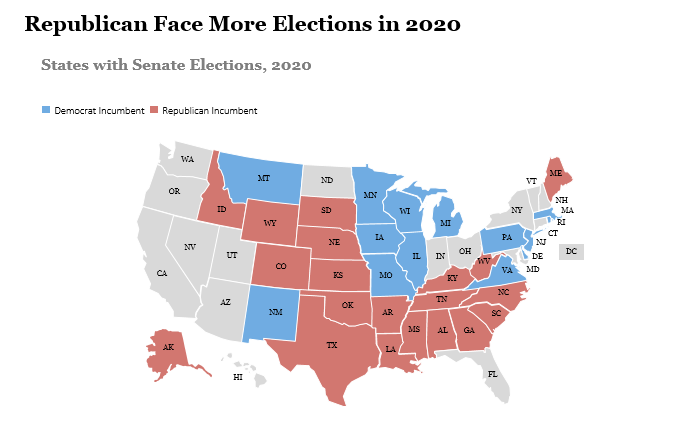

By the same token, the Republicans have held a majority since the 114th Congress. This means that most of the senators that are up for reelection in 2020 will be Republicans. Figure 3 shows the electoral map for the 2020 Senate election, which will feature more Republican senators defending their seats and a better chance for Democrats to regain control of the Senate.

Figure 2 – Senatorial map of the 2018 election

Figure 2 – Senatorial map of the 2018 election

Figure 3 – Senatorial map of the 2020 election

The net result of this memory effect? Increased stability.

Presidents are elected every four years with term limits of two terms. Again, if we don’t like the president that we elect, we only have to “suffer” him/her for a limited period of time and not elect him again. Provided that we vote.

The only governing arm without a term limit is the judiciary. The federal court system consists of District Courts, Circuit Courts, and the US Supreme Court, each of which are comprised of judges who have been recommended by presidents and approved by the Senate. These judges are markers of the political fluctuations in the other two branches of government. The assumption is that after gaining the security of lifetime appointments, they are free to practice independently of the political setting that was responsible for their election. Sometime this works, often it doesn’t. Brett Kavanaugh’s addition, for example, remains fraught with potential partisanship. Also, the recent hospitalization of Ruth Bader Ginsburg is an acute reminder of the fragility of this arm of the government.

Appreciate the clarity of explanation.! Looking forward to your next post!!