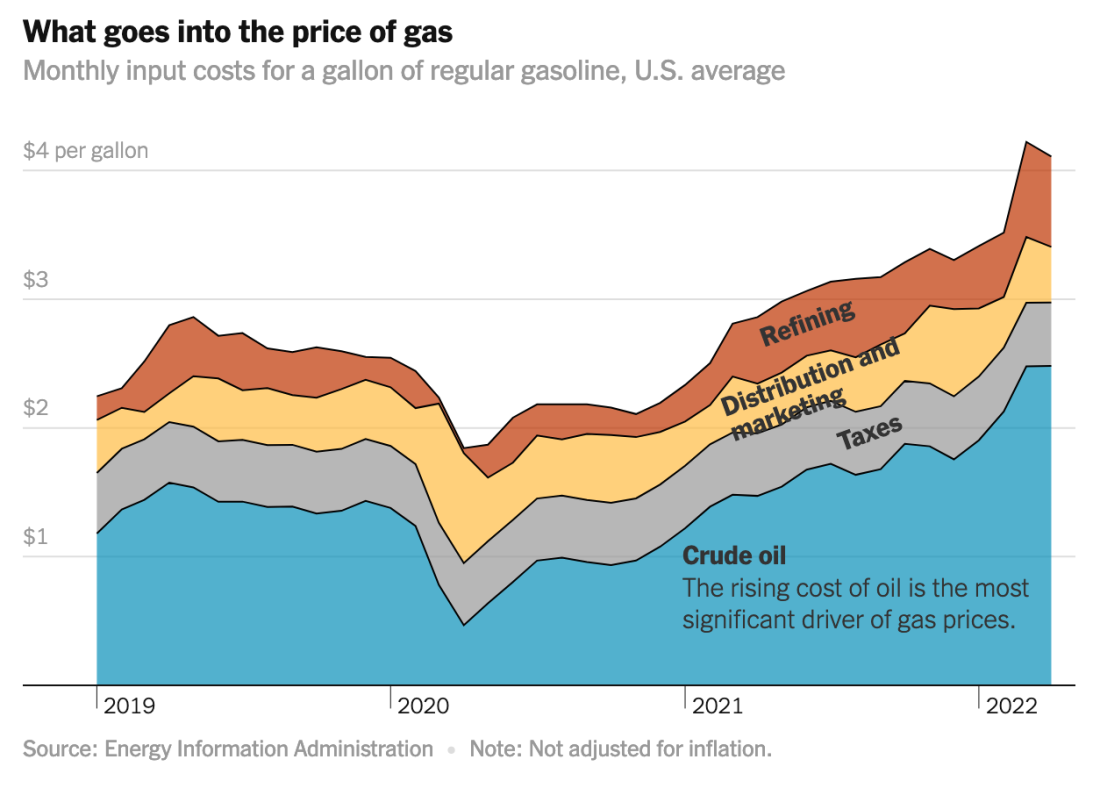

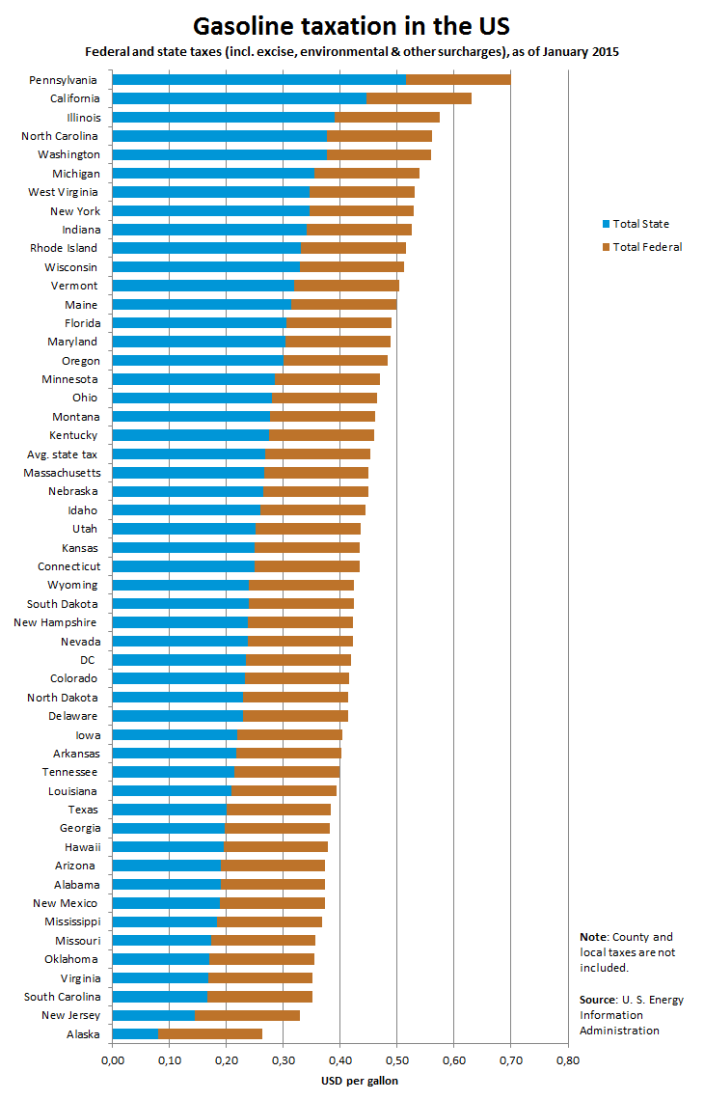

Two weeks ago (June 14, 2022), I referred to Gina Raimondo, the US Commerce Secretary, whose thoughts of gas prices CNN summarized: “there is not much more the White House can do to tackle record high gas prices for Americans, [Raimondo cast] blame on Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.” The secretary restricted herself to top-down activities coming from the White House. More recently, President Biden tried to prove her wrong by proposing that congress enact a temporary (3 month) “holiday” from federal taxes. The reaction in the political arena was not encouraging. The arguments against such proposals are well known. Figure 1 shows the components of gasoline pricing over the last three years. Taxes are actually a relatively small component in gas pricing; it’s obvious from the figure that the inflation in gas prices is driven primarily by the price of crude oil, which is determined internationally. Furthermore, Figure 2 shows that in most states, state taxes are higher than federal ones. President Biden added a recommendation that states join the “tax holiday.” However, many voices predict that such measures will not help: oil companies will just “absorb” the saved tax into their own balance-sheet, with no impact or relief for consumers.

The New York Times piece where I found Figure 1 (based on the Energy Information Administration data) summarizes some of the issues:

Gas prices in the United States are at record highs. And even when adjusting for inflation, they are on average at levels rarely seen in the last 50 years, including during the energy crisis of the late 1970s. When fuel prices go up, consumers are hurt directly at the pump, but also indirectly when higher transportation costs raise prices on everything from food to diapers to construction materials.

The single biggest factor driving the spike now is the price of crude oil. As of April, according to the Energy Information Administration, the cost of the raw material accounted for 60 percent of the price of a gallon of regular gasoline. That compares to 52 percent the same time a year ago, and just 25 percent in April 2020 — when the pandemic sapped demand for fuel, along with most other goods and commodities.

Figure 1 – Components of gas pricing

Figure 2 – Composition of gas taxes

The most effective remedy is not top-down but bottom-up: drive less, try not to drive alone, be comfortable with slightly lower heating temperature, keep track of your use of electricity, and wherever possible, follow Phil Gallagher, last week’s guest blogger, and try to supplement your energy input with fossil-independent sources. For some of us, these choices mostly have to do with convenience and will not have major impacts on our lifestyle. But, for many who live from paycheck to paycheck and are dependent on driving to earn livelihood, some of these changes are existential.

I have repeatedly mentioned selective measures to help many of the “losers” in this needed energy transition (see the December 18, 2018 blog about the Yellow Vest demonstrations in France). In this context, we do need top-down help. Particular attention should be now directed toward Europe. Some of the difficulties that Europe is now facing, and the steps that they trying to take to overcome them, are summarized in the following WSJ piece:

Europe is hitting roadblocks as it tries to find alternatives to Russian gas in the Middle East and North Africa, as talks with big producers like Qatar, Algeria and Libya have become complicated.

The issues that have snarled negotiations range from the pricing of Qatari gas to stability in Libya and the politics of Western Sahara, a disputed North African territory. The challenges mark another indication that Europe will struggle to fully replace energy from Russia, which supplies 38% of the continent’s natural gas.

The WSJ piece mainly focuses on the short-term resiliency requirements of moving Europe away from its dependence on the Russian energy supply, especially given the immediate energy needs for electricity and heat in preparation for the coming winter. Resilience on such a short time scale invariably requires replacing one source of fossil fuels with another. Fortunately, Europe is much more advanced than many other regions in its transition to sustainable energy sources. This brings into focus another aspect of the European energy transition that can be adapted globally: modernizing the power grid by extending its boundaries as far as possible.

The US is not dependent on import of fuel supply from belligerent countries. However, many states are still fully dependent on coal as their primary energy source and climate impacts vary across states, commensurate with the requirements of their electricity load. Resiliency necessitates a timely transfer of power supply to prevent massive shortages. There is progress in all these areas, but it is too slow.

Our collective and individual challenges should not be used to weaponize difficulties in addressing energy distribution as a tool to replace the people in power. Instead, we need to work together to help solve these important challenges by increasing our efficiency in using the available energy.

In this globally connected environment, the interplay between top-down and bottom-up efforts to control various aspects of our lives is all consuming. We are all living through it. I will return to this in future blogs.

according to the Washingtonpost.com, I quote: “Average price for a regular unleaded gallon of gas. These higher energy prices seep into almost every major part of the economy. They drive up the costs for electricity, transportation, shipping, logistics, air travel, agriculture, fertilizer, and the production of other commodities.” this is merely an example of how this affects Americans. I know in my country Montenegro when the inflation of gas prices started, many people struggled on buying gas. it cost them 100 euros for a full tank. most people there anyway has German diesel-efficient cars, but despite this inflation, many people weren’t able to afford it