As an old guy who still teaches students and does scientific research, I have to be up-to-date on the science that relates to what I do. To study and teach climate change, I have to be current not only with regards to the relevant scientific literature but also with daily current events on a global scale. Therefore, I supplement my intake of daily papers and magazines with a broader spectrum of news sources. Fortunately (or not, debatably), our internet age provides a variety of gadgets to facilitate this.

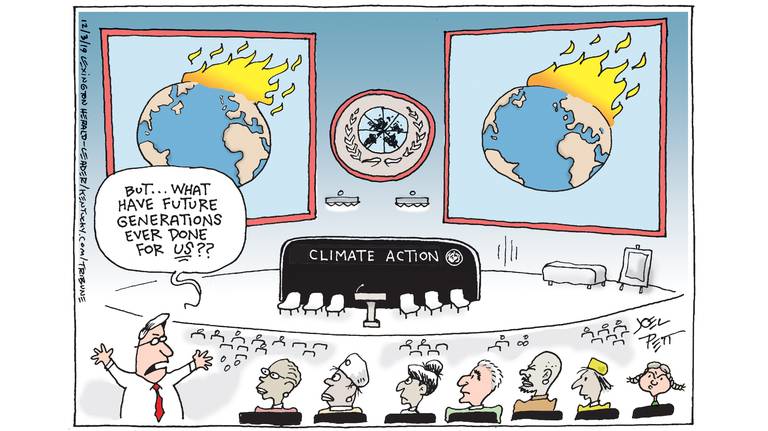

In addition to the other outlets and media types, I get the “News in Cartoons,” which I greatly appreciate. Scanning through the cartoons, I often come across ones that directly relate to some topic that I have been discussing. Occasionally, I post these on blogs to illustrate certain points. The opening cartoon on this blog was published around the same time as our 73-year-old president was having a Twitter fight with 16-year-old Greta Thunberg (see the August 6, 2019 blog for more on Greta); I see it as ironically appropriate. The cartoon satirically advocates a quid pro quo from our children and grandchildren. They want us to fight climate change but what will they give us in return?

To get a bit more serious, let’s focus on dollars and cents and look at what kind of inheritance we are leaving future generations. If I search this blog for “economic impact” or “economic impact of climate change,” I find more than 50 entries.

Looking outside my blog, I am citing part of an opinion piece from The New York Times, written by Naomi Oreskes and Nicholas Stern. It describes a recent report, which argues that today’s economic reports strongly underestimate both short-term and especially long-term consequences of the costs of climate change to the economy. Nicholas Stern is also a co-author of the report:

“Climate Change Will Cost Us Even More Than We Think”

Economists greatly underestimate the price tag on harsher weather and higher seas. Why is that?

For some time now it has been clear that the effects of climate change are appearing faster than scientists anticipated. Now it turns out that there is another form of underestimation as bad as or worse than the scientific one: the underestimating by economists of the costs.

The result of this failure by economists is that world leaders understand neither the magnitude of the risks to lives and livelihoods, nor the urgency of action. How and why this has occurred is explained in a recent report by scientists and economists at the London School of Economics and Political Science, the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research and the Earth Institute at Columbia University.

One reason is obvious: Since climate scientists have been underestimating the rate of climate change and the severity of its effects, then economists will necessarily underestimate their costs.

…Typically, our estimates of the value or cost of something, whether it is a pair of shoes, a loaf of bread or the impact of a hurricane, are based on experience. Statisticians call this “stationarity.” But when conditions change so much that experience is no longer a reliable guide to the future — when stationarity no longer applies — then estimates become more and more uncertain.

Hydrologists have recognized for some time that climate change has undermined stationarity in water management — indeed, they have declared that stationarity is dead. But economists have by and large not recognized that this applies to climate effects across the board. They approach climate damages as minor perturbations around an underlying path of economic growth, and take little account of the fundamental destruction that we might be facing because it is so outside humanity’s experience.

A second difficulty involves parameters that scientists do not feel they can adequately quantify, like the value of biodiversity or the costs of ocean acidification. Research shows that when scientists lack good data for a variable, even if they know it to be salient, they are loath to assign a value out of a fear that they would be “making it up.”

Therefore, in many cases, they simply omit it from the model, assessment or discussion. In economic assessments of climate change, some of the largest factors, like thresholds in the climate system, when a tiny change could tip the system catastrophically, and possible limits to the human capacity to adapt, are omitted for this reason. In effect, economists have assigned them a value of zero, when the risks are decidedly not.

…A third and terrifying problem involves cascading effects. One reason the harms of climate change are hard to fathom is that they will not occur in isolation, but will reinforce one another in damaging ways. In some cases, they may produce a sequence of serious, and perhaps irreversible, damage.

…In a worst-case scenario, climate impacts could set off a feedback loop in which climate change leads to economic losses, which lead to social and political disruption, which undermines both democracy and our capacity to prevent further climate damage. These sorts of cascading effects are rarely captured in economic models of climate impacts. And this set of known omissions does not, of course, include additional risks that we may have failed to have identified.

I will look deeper into the report next week. Meanwhile, if you want to read the whole thing, you can find it here.

This op-ed is so important that I felt it necessary to establish the credentials of the two authors. Stern’s biography on Wikipedia includes a description of what is known as the “Stern Report,” which serves today as one of the most influential attempts to analyze the economic impacts of climate change. Reading the piece above, I believe that the new report is a self-criticism of Stern’s original report.

Nicholas Stern

He is professor of economics and government and chair of the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment at the London School of Economics (LSE), and 2010 Professor of Collège de France. From 2013–2017, he was President of the British Academy.

The Stern Review (2005–2006)[edit]

The Stern Review Report on the Economics of Climate Change was produced by a team led by Stern at HM Treasury, and was released in October 2006. In the review, climate change is described as an economic externality. Stern has subsequently referred to the climate change externality as the largest ever market failure:

Climate change is a result of the greatest market failure the world has seen. The evidence on the seriousness of the risks from inaction or delayed action is now overwhelming … The problem of climate change involves a fundamental failure of markets: those who damage others by emitting greenhouse gases generally do not pay[9]

Regulation, carbon taxes and carbon trading are recommended to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. It is argued that the world economy can lower its greenhouse gas emissions at a significant but manageable cost. The review concludes that immediate reductions of greenhouse gas emissions are necessary to reduce the worst risks of climate change. The review’s conclusions were widely reported in the press. Stern’s relatively large cost estimates of ‘business-as-usual’ climate change damages received particular attention.[10][11] These are the estimated damages that might occur should no further effort be made to cut greenhouse gas emissions.

There has been a mixed reaction to the Stern Review from economists. Several economists have been critical of the review,[12][13] for example, a paper by Byatt et al. (2006) describes the review as “deeply flawed”.[14] Some have supported the Review,[15][16] [17] while others have argued that Stern’s conclusions are reasonable, even if the method by which he reached them is incorrect.[18] The Stern Review team has responded to criticisms of the review in several papers.[19] Stern has also gone on to say that he underestimated the risks of climate change in the Stern Review.[20]

Stern’s approach to discounting has been debated amongst economists. The discount rate allows economic effects occurring at different times to be compared. Stern used a discount rate in his calculation of the effects of “business-as-usual” climate change damages. A high discount rate reduces the calculated benefit of reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Using too low a discount rate wastes resources because it will result in too much investment in cutting emissions (Arrow et al., 1996, p. 130).[21] Too high a discount rate will have the opposite effect, and lead to under-investment in cutting emissions. Most studies on the damages of climate change use a higher discount rate than that used in the Stern Review. Some economists support Stern’s choice of discount rate (Cline, 2008;[22] Shah, 2008[17] Heal, 2008)[23] while others are critical (Yohe and Tol, 2008;[24] Nordhaus, 2007).[25]

Another criticism of the Stern Review is that it is a political rather than an analytical document. Writing in the Daily Telegraph newspaper, columnist Charles Moore compared the Stern Review to the UK Government’s “dodgy dossier” on Iraqi weapons of mass destruction.[26]

Naomi Oreskes

(born November 25, 1958)[1] is an American historian of science. She became Professor of the History of Science and Affiliated Professor of Earth and Planetary Sciences at Harvard University in 2013, after 15 years as Professor of History and Science Studies at the University of California, San Diego.[2] She has worked on studies of geophysics, environmental issues such as global warming, and the history of science. In 2010, Oreskes co-authored Merchants of Doubt which identified some parallels between the climate change debate and earlier public controversies.[3]

Clearly, Nicholas Stern’s aim with the op-ed was to guide people to the recent report. Short of that, he was appealing to policy makers and the general public to take the new analysis of the economic impact more seriously—hopefully helping to minimize it. It is a bit more puzzling to me why Naomi Oreskes is a co-author. She is neither a co-author of the recent report nor a member of one of the major institutions that sponsored it. My hypothesis is that she lent her familiarity with deniers to the strategy of grabbing people’s attention. Her book, Merchants of Doubt, is a must-read for anybody interested in the fights over tobacco, climate change, the ozone hole, and any other instances where science has come up against societal norms. While the article is several months old, the authors have since published a Q&A.

While reading this, I found it both interesting and frustrating that despite believing the cost of climate change was lower than it really was, the response from many was to ignore it instead of intervening early on before climate change gets worse and the cost gets higher. By the time climate change becomes too destructive to put off any longer and it becomes necessary to pay the price of it, the cost will be a lot higher. It’s not from an inability to understand this that people and governments ignore climate change as an issue, but from an unwillingness to react as long as the effects are not immediate.

I’ve noticed that people are reluctant to spend money on improving the climate because they don’t believe it affects them or because they don’t see immediate results from their efforts. However, this is short-term thinking. The changes in climate will affect future generations. We might not see the fruits of our labour now were we to make a large-scale effort for change, but the changes will come.

I’ve been employing delayed gratification into my daily life and I’ve found that it is much more conducive to me getting stuff done and setting up a better future for myself. It would be the same thing with climate change. Investing money upfront for the climate now might not yield immediate results, but it would lead to results later, and those would be worthwhile

It’s frustrating to read this, as the content just makes one feel so aware of the impending doom of everything, and yet powerless to counter it. In my journalistic studies, I am particularly interested in water as a resource, so in my reading of this, a bit that jumped out to me was the part about water stationarity being dead. Just that bit itself speaks louder than the one line it occupies because it makes clear how ineffective our current mainstream understanding of climate change is.

I see how people and governments are resistant on spending money upfront, especially a significant amount when return is so far fetched. We live in a world of consumerism and instant gratification, so unless you see clear results from your investment short-term it is much harder to commit. I personally do not agree with it, but I can see why people are wary, when in their mind there are more pressing issues than climate change that still seems too distant to them.

It is clear that the reason the climate is the way it is now because the older generation didn’t take climate change as seriously as they should’ve. To many then (and even now), it “doesn’t affect them so why should they care?” However, it does affect everyone living on this planet. The future is for our future families and, if we don’t do something about climate change now, our future child, nephew, niece, cousin, and/or grandchild will pay the price of inheriting an inhabitable world. As the New York Times article stated, climate change will cost us more if we don’t do anything about it. Instead of paying for renewable energy to help better the planet, we will be paying for fire retributions. It is important for us to take climate change seriously and do whatever we can to stop the human destruction of the planet.

It makes sense to spend more money now if it will end up helping our planet and future generations in the long run. Change is expensive, but that should not be the reason for not implementing it if it will help slow down the negative effects of climate change.