I am starting to write this blog on International Holocaust Remembrance Day, Wednesday, January 27th. Today marks 71 years since the liberation of Auschwitz. The end of the week will also mean the beginning of a new semester and back to teaching for me.

I had a cheerful time over the semester break reading about both the Holocaust and the consequences of a nuclear Armageddon before my trip to Cuba. The Holocaust book was Black Earth: The Holocaust as History and Warning by Timothy Snyder. One of my colleagues, a history professor at my school, recommended it to me as the only book he knows of that makes an explicit connection between climate change and the Holocaust. I had heard plenty about The Cold and the Dark: The World after Nuclear War by Paul R. Ehrlich, Carl Sagan, Donald Kennedy and Walter Orr Roberts, but had never read it.

The connection between climate change and the Holocaust is a repeated theme here on Climate Change Fork, starting with my first blog. A new aspect that emerged to me reading Snyder’s book was the importance of the destruction of state in the Nazis ability to industrialize the murder of Jews. The Nazis believed that annihilating Jews would rebalance the planet to a German advantage. To accomplish this, the Germans set about destroying other states with large Jewish populations. They absorbed Austria, tore apart Czechoslovakia and demolished Poland. In fact, some parts of Poland were hit twice: once by the Soviets and once by the Germans. The destruction of the three Baltic States and significant parts of the western Soviet Union accounted for nearly 5 million murdered Jews. That number represents an estimated 90% of the Jewish population of those states. States that were occupied by the Germans but remained functional, such as France, Holland, Belgium, Denmark, Norway, and even Germany, lost a relatively smaller percentage of their Jewish population. Snyder argues that as long as a state functions – in any capacity – it has the power and obligation to protect its citizens.

My visit to Cuba gave a very strong impression that the United States did almost everything in its power to destroy the state government of Cuba following the 1959 revolution in which Castro’s forces deposed Batista’s regime. The United States tried to accomplish this destruction primarily via economic means (i.e. through the embargo and other measures). That said, there were also several documented attempts to reach the same goal using military means, mainly through CIA activities; the most publicized of these was the Bay of Pigs infiltration.

Paul Ehrlich and Carl Sagan’s book summarizes the 1983 Conference on the Long-Term Worldwide Biological Consequences of Nuclear War. It quantifies the physical global events that would take place in the aftermath of a nuclear war. Most of the cases that it shows assume given destructive powers that are a mere fraction of the nuclear arsenal that was available at the time of the Cuban Missile Crisis both to the Americans and to the Russians. The concept of a nuclear winter arose from these discussions.

One of the most striking yet simple questions came from the audience after Carl Sagan’s talk: What would happen after a “successful” first strike by one of the sides? The definition of a “successful” first strike was always understood to be one large enough to destroy the capabilities of the other side to respond. Carl Sagan answered, and the other participants agreed, that in most likelihood, if the first strike were to pass some minimum threshold of megatons exploding (Larger than at Hiroshima and Nagasaki but a small fraction of the two superpowers’ arsenals), the striker would commit a collective suicide because the impact of the strike would be global. This response echoes my definition of uncontrolled anthropogenic climate change as self-inflicted genocide on a global scale.

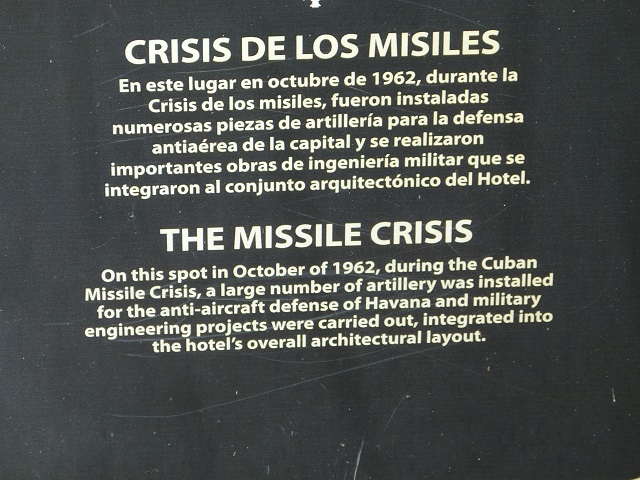

Following its revolution, the new Cuban government didn’t take the hostilities by the United States lightly; nor did it submit to our demands. This was at the height of the Cold War and Cuba found a formidable ally in the Soviet Union. This led, among other things, to the Cuban Missile Crisis. The two photographs were taken on the grounds of one of Havana’s most famous hotels: Hotel Nacional. While the hotel is now swarming with rich Western tourists – many of them Americans, in 1962 the hotel was converted into a major anti-aircraft defense position to protect against an air attack. The bunkers that remain remind us that this event brought the US, Cuba, and Russia the closest to a major nuclear conflict since 1945. As Carl Sagan and Paul Ehrlich aptly pointed out, such a conflict would not have stayed confined to these three countries.

Fortunately, the US and Cuba are now in the process of thawing their relationship, thanks mostly to President Obama’s executive orders. The embargo was put in place by Congress and cannot be lifted without a matching Congressional resolution, but that option is not currently on the table. Two of the leading Republican presidential candidates, Senators Ted Cruz and Marco Rubio, are second generation Cuban immigrants with families that left Cuba either directly before or after the revolution. Both of them want Cuba to bend to the US’s whims before they will agree to lift the embargo.

Very interesting comment by Snyder about the state and it’s purpose of “protecting its citizens”. Plato argued that the state precedes man and that without the state, man is either God or beast. Wael B. Hallaq argues in his book “The Impossible State” that this conception of the state renders its interests superior and exclusive to those of man. This line of reasoning would suggest the idea that the state will indeed sacrifice man in order to uphold the collective interest of the state. The interests of the state are so often defined by those who hold power. If those who have a monopoly over power do not support the interests of the common man (such as taking necessary measures to mitigate the effects of climate change), then we’re in trouble.