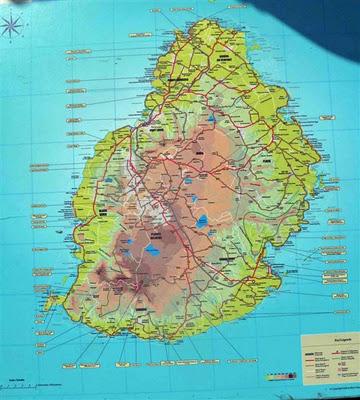

In July, I am going to attend the Fifth International Conference on Climate: Impacts and Responses, to be held in the island of Mauritius. This is the same meeting that was held last year in Seattle Washington, which I described in my July 16, 2012 blog. My wife and I have decided to use the meeting as a pretext for an extended tour of Southern Africa. We will be back in the beginning of August.

I have pre-written a few blogs (including this one) to be published during my absence. In the weeks after my return I will try (provided outside events do not supersede my plans – we remember that the future is ever uncertain) to focus on the forecasts of climate change impact on Southern Africa. I will put particular emphasis on islands such as Mauritius and Madagascar, as viewed through the “official” eyes of the IPCC and the conference participants.

The scheduled program of the conference is copied below. I will be presenting a talk, Bottom-up Mitigation of Global Climate Change: Fuel Selection and Classroom Exposure, along with my partner, Prof. Lori Scarlatos, from StonyBrook University, where we will give updates of our progress in the online/offline game/simulation that we presented last year. The focus is to quantitatively compare a world based on student choices with the real world parameters.

FIFTH INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON

CLIMATE CHANGE: IMPACTS AND RESPONSES

PORT-LOUIS, MAURITIUS

18-19 JULY 2013

www.on-climate.com

Arrival of Chief Guest

Hon Devanand Virahsawmy, Minister of Environment & Sustainable Development, Republic of Mauritius

Welcome Address

Dr G. Raj Chintaram

Chairperson ANPRAS/ Conference Co-Chair; Izabel Szary, Common Ground

Welcome Address

Hon Devanand Virahsawmy, Minister of Environment & Sustainable Development

Minister & Common Ground Declare Conference Open

Plenary Session

Dr Richard Munang, Climate Change Adaptation & Development Programme for Africa, United Nations

Plenary Room

Date of Snowmelt in the Arctic and Variations with Climate Patterns and Oscillations

Dr. James Foster, NASA, United States — Dr. Judah Cohen, Verisk Analytics, United States

Snowmelt changes observed since the late 1980s have been step-like in nature rather than continuous. It appears in some instances these changes are related to a climate regime shift.

Effects of CO2-driven pH Decline on the Early Developmental Stages of Sea Urchins from across the World

Emily Joy Frost, University of Otago, New Zealand

The impact of ocean acidification on the ion-regulation physiology, general physiology and ion-regulation genetics on an Antarctic (Sterechinusneumayeri), tropical and temperate (Evechinuschloroticus) sea urchin species

Mitigation Strategies

Room 1

Adaptation to Climate Change: Israel and the Eastern Mediterranean

Prof. Mordechai Shechter, Interdisciplinary Center (IDC) Herzliya, Israel

This paper assembles the existing scientific research regarding adaptation to climate change, identifies research gaps, and defines the risks and consequences of climate change in various sectors.

Bottom-up Mitigation of Global Climate Change: Fuel Selection and Classroom Exposure

Micha Tomkiewicz, Brooklyn College of CUNY, United States — Prof. Lori Scarlatos, Stony Brook University, United States The talk will present progress in the online/offline game/simulation that was previously presented here. The focus is to quantitatively compare world based on student choices with the real world parameters.

Climate Change, Mitigation, and Nationally Appropriate Action: The Road to Nationally Appropriate Definitions

Cecilia Therese T. Guiao, -, Philippines

A Philippine perspective on mitigation targets and NAMAs, the current state of Philippine policies, and important factors to be considered by public and private sectors in line with sustainable development.

Climate Change Challenges

Room 2

Carbon Neutral Mine Site Villages: Calculation and Offset Mechanism

Mr David Goodfield, Murdoch University, Australia — Dr. Martin Anda, Murdoch University, Australia — Prof. Goen Ho, Murdoch University, Australia

Calculation of the carbon footprint of minesite villages is a complex process. A sustainable solution to offset the total carbon is equally hard to determine and justify to the stakeholders.

Designing an Education and Training Framework to Build Local Capacity in Climate Change Adaptation and Low Carbon Livelihoods

Dr Shireen Fahey, University of the Sunshine Coast, Australia — Geoff Dews, University of the Sunshine Coast, Australia — Dr. Noel Meyers, University of the Sunshine Coast, Australia — Graham Ashford, The University of the Sunshine Coast, Australia

An education and training framework to build local capacity in climate change adaptation and low carbon livelihoods in the Indian Ocean region

Fictional Depictions of Climate Change: An Analysis of Themes from Contemporary Climate Change Literature

Dr. Danielle Clode, Flinders University, Australia — Monika Stasiak, Flinders University, Australia

This paper explores emerging themes in contemporary climate change literature as a reflection of, and influence on, broader community perceptions about the world of the future.

Imagining Sustainable Futures for the Chagos Archipelago: Environmental Conservation versus Livelihood and Development?

Dr Laura Jeffery, University of Edinburgh, United Kingdom

Conflicting projections do not demonstrate conclusively whether proposed economic activities and infrastructural development in the Chagos MPA could make human habitation feasible while simultaneously enabling effective environmental conservation.

Humankind and the Environment Attitude towards Small Hotel Greening Initiative: Perspective from Tourists and Hoteliers of the Eastern Coast of Mauritius

Vanessa GB Gowreesunkar, University of Technology Mauritius, Mauritius — Dandini Thondrayen, ANPRAS, Mauritius — Sarita Nuckcheddee, ANPRAS, Mauritius — Kirti Rukmani Devi Tohul, ANPRAS, Mauritius — Jayveer Kumar Lobin, ANPRAS, Mauritius

This study investigates the attitude of tourists and small hotel managers towards green hotel initiative and attempts to make the case for its application within small hotels found in Mauritius.

Impacts of Climate Change-induced Conflict on Pastoralism and Human Security in Northwestern Kenya: Impacts of Water and Pasture Scarcity on Livelihoods

Moses Hillary Akuno, United Nations University Institute for Sustainability and Peace, Japan

Recent prolonged droughts and unpredictable weather changes have had a direct impact on conflict, turning it to a more frequent and destructive affair.l

Prospects of Payment for Environmental Services (PES) in the Feng Shui Forest in Peri- urban Hong Kong: A Policy Instrument for Climate Change Discourse

Prof. Lawal Mohammed Marafa, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, China — K.C. Sunil, The Chines University of Hong Kong, China

Feng Shui forests are part of Hong Kong’s peri-urban ecosystem, which provides environmental services. This paper examines the services and discusses prospects for policy instruments in delivering ecosystem services.

New Climate Change Information Framework for Behavior Change: Sharing the Framework to Facilitate Dialogue and Action on Climate change

Dr Candice Howarth, Anglia Ruskin University, United Kingdom

A climate information framework is presented based on UK research to encourage action and sustainable behaviour change. It hopes to generate dialogue on its application to different case study scenarios

Response of Coral Reef Fish to Simulated Ocean Acidification

Prof., Dr. Saleem Mustafa, Universiti Malaysia Sabah, Malaysia — ShigeharuSenoo, Universiti Malaysia sabah, Malaysia — Marianne Luin, Universiti Malaysia Sabah, Malaysia

Ocean acidification driven by climate change is accelerating and impact on marine life is imminent. This paper examines how coral reef fish, groupers, are directly affected by acidification.

Coastal Communities: Special Topics

Room 1

Characteristics of Respondents in a Climate Change-affected Coastal Area in Bangladesh

Russell Kabir, Middlesex University, United Kingdom

This study explores the characteristics of coastal people of Bangladesh related to socio-economic, environmental, and demographic issues, water and toilet facilities, natural resources and access to mass media.

Exploratory Study about the Impacts of Islets Tourism in the ‘MTVC’ Region in Eastern Mauritius

Dr. Gowtam Raj Chintaram, ANPRAS, Mauritius — WardaMohungoo, ANPRAS, Mauritius — YogshresthSabandy, ANPRAS, Mauritius — Louis Clarel Salomon, ANPRAS, Mauritius

The small nature and uniqueness of islets have made such destinations increasingly popular. The appeal for micro destinations have popularized offshore islets tourism but also created serious environmental threats.

Indigenous Knowledge and Climate Change: Settlement Patterns of the Past to Future Resilience

Phillip Roos, Deakin University, Australia

Aboriginal settlement patterns of the past provide adaptation solutions for a proposed design-based adaptation model for settlements along the Australian coast impacted by climate change and sea level rise.

Using Integrated Models for Adaptation Planning: Evaluating Adaptation Investments for the Tourism Sector in the Coastal Zone of Mauritius

Graham Ashford, The University of the Sunshine Coast, Australia — Dr. Noel Meyers, University of the Sunshine Coast, Australia

— Geoff Dews, University of the Sunshine Coast, Australia — Dr Shireen Fahey, University of the Sunshine Coast, Australia Mauritius’ coastal pilot study to evaluate adaptation and disaster risk reduction strategies using economic cost-benefit analysis in combination with sustainable development criteria as part of a multi-criteria decision making process

Large Scale Implications

Analysis of Tropical Cyclones Dynamics and Its Impacts

Yee Leung, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, China

The paper presents the dynamics of tropical cyclone recurvatures, landfalls and intensities under climate anomalies, particularly in ENSO years. It also introduces a powerful system for analysis, prediction and decision-making.

Assessing Hydrological Impacts of Climate Change Using Monthly Water Balance Models

Dr. Yongqin Chen, Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of China

This paper presents a study that analyzes and compares the performance and underlying mechanism of six monthly water balance models in a climate change assessment of hydrological impacts.

Climate Model Intercomparison at the Dynamics Level

Prof. Anastasios Tsonis, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, United States — Dr. Karsten Steinhaeuser, University of Minnesota, United States

A systematic comparison of CMIP3 forced and unforced runs for the purpose of evaluating the robostness of climate simulations and projections

Water and Climate Change: An Integrated Approach to Address Adaptation Challenges

Dr. Udaya Sekhar Nagothu, The Norwegian Institute for Agricultural and Environmental Research, Bioforsk, Norway

The study addresses how improved integrated water management practices could increase agricultural production and food security, protect natural systems and be a “game changer” for national food security.

Climate Change Challenges

F1 Progeny of White Fulani and New Jersey Cows: A Panacea to Climate Change Effect on Dairy Cow Productivity in North Central Nigeria

Prof. Abiodun Adeloye, University of Ilorin, Ilorin , Nigeria, Nigeria

The growth performance and suitability of the F1 progeny of indigenous White Fulani and exotic New Jersey cattle is studied in the North Central region of Nigeria.

Lost Polar Bear in London: Visualising Climate Change and U.K. National Press Coverage of the Rio+20 Summit

Prof. Alison Anderson, University of Plymouth, UK, United Kingdom

This paper examines the role that celebrity advocacy played in the reporting of the 2012 Rio Earth Summit in the British newspaper press.

Modern Bioenergy Technologies for Universalizing Energy Access in India: Solving the Conflicting Challenges of Climate Change and Development

Dr. Balachandra Patil, Indian Institute of Science, India

This paper details an innovative approach to India’s energy challenges: limited access to modern energy services, the need to expand energy systems to achieve economic growth, and climate change threats.

Date of Snowmelt in the Arctic and Variations with Climate Patterns and Oscillations

Dr. James Foster, NASA, United States — Dr. Judah Cohen, Verisk Analytics, United States

Snowmelt changes observed since the late 1980s have been step-like in nature rather than continuous. It appears in some instances these changes are related to a climate regime shift.

Effects of CO2-driven pH Decline on the Early Developmental Stages of Sea Urchins from across the World Emily Joy Frost, University of Otago, New Zealand

The impact of ocean acidification on the ion-regulation physiology, general physiology and ion-regulation genetics on an Antarctic (Sterechinusneumayeri), tropical and temperate (Evechinuschloroticus) sea urchin species

Agriculture and the Impacts of Change

Impacts of Climate Change on Supply Response for Maize in Kenya: Evidence from Cointegration Analysis

Dr. RakhalSarker, University of Guelph, Canada — Dr. Jonathan Nzuma, University of Nairobi, Kenya — Shashini Ratnasena, University of Guelph, Canada

Maize is the most important staple in Kenya. This paper attempts to determine the impacts of climate change on maize production in Kenya.

Priority Assessment of Climate Change Adaptation and Mitigation Strategies: Application of Analytical Hierarchy Process Modelling

Prof. Nazrul Islam, University of the Sunshine Coast/Sustainability Research Centre, Australia — Dr Nasir Uddin, Sunshine Coast University, Australia — Dr. Angela Wardell-Johnson, University of the Sunshine Coast, Australia — Dr. Tanmoy Nath, Australia

This study assesses priority rankings of climate change adaptation and mitigation strategies and provide important information to food industry stakeholders for strategic interventions in regional food security in Australia.

Strategic Interventions to Manage Climate Change for Food Security: Modelling for Best Fit Using Evidence of Horticulture and Dairy in Australia

Dr Nasir Uddin, Sunshine Coast University, Australia — Dr. Angela Wardell-Johnson, University of the Sunshine Coast, Australia

— Prof. Nazrul Islam, University of the Sunshine Coast/Sustainability Research Centre, Australia — Dr. Tanmoy Nath, Australia This study used a number of scenarios to provide evidence of the links between CC risks, adaptive capacities, and adaptation/mitigation strategies for strategic interventions in the food security of Australia.

Gas Emissions: Implications

Carbon Budget Method Based on GIS

Anand Sookun, Mauritius

A geostatistical method adapted to GIS has been developed to account for the terrestrial carbon budget which involve carbon emissions net of carbon uptakes by plants and soil.

Energy Labeling and Residential House Prices: Some Evidence from the United Kingdom

Prof. Pat McAllister, University College London, United Kingdom — Dr. Anupam Nanda, University of Reading, United Kingdom

— Prof. Peter Wyatt, University of Reading, United Kingdom — Dr. Franz Fuerst, University of Cambridge, United Kingdom

This paper outlines the results of the first large-scale empirical analysis of the effects of certificates on energy performance on residential property prices in England and Wales.

Ocean Acidification: A Major Threat?

Diyashvir Kreetee Rajiv Babajee, African Network for Policy Research & Advocacy for Sustainability, Mauritius, Mauritius — Dr. Gowtam Raj Chintaram, ANPRAS, Mauritius

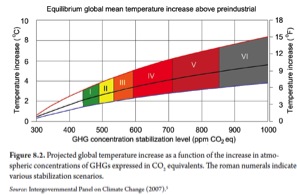

We use a global CO2 model to make predictions of the pH of oceans in 2100 for 5 cases based on possible measures to reduce CO2 emissions.

Policies and Programs: Climate Change

Bargaining for Nature in China’s Urban Planning Practice: Insights from the Tianjin Eco- City Project

Assoc. Prof. Jiang Xu, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, China

This presentation uses Tianjin Eco-City Planning as an example to illustrate how Chinese urban planners bargain for ecological value of spaces under the great pressure to commodify urban spaces.

Capital and Climate Change: Evaluating Capacity for Strategic Intervention

Dr. Angela Wardell-Johnson, University of the Sunshine Coast, Australia — Dr Nasir Uddin, Sunshine Coast University, Australia

— Prof. Nazrul Islam, University of the Sunshine Coast/Sustainability Research Centre, Australia — Dr. TanmoyNath, Australia

— Brian Richard Stockwell, Department of State Development Infrastructure and Planning, Australia

This research used a framework of seven capitals represented Triple Bottom Line values to test capacity to implement climate change intervention strategies through identified risk scenarios.

Domestic Policy Commitments to International Climate and Sustainability Agreements: The Role of Employer Organisations and Trade Unions

Peter J. Glynn, Bond University, Australia — Prof. RosTaplin, University of New South Wales, Australia

While domestic policy overtly reflects international climate agreements, the economic and social elements of the agreements are less obvious but are nevertheless embedded in the policy framework.

Managing for Ecological Resilience: Case Studies from Developing Countries

Geoff Dews, University of the Sunshine Coast, Australia — Graham Ashford, The University of the Sunshine Coast, Australia — Dr. Noel Meyers, The University of the Sunshine Coast, Australia — Dr Shireen Fahey, University of the Sunshine Coast, Australia

We use selected cases studies to demonstrate that implementing existing environmental management along with traditional management approaches can produce resilient ecosystems that promote ecosystem-based adaptation strategies.

Societal Impacts of Climate Change

Analysis of Climate Dependent Infectious Diseases: A Case Study of Chennai

Divya Subash Kumar, Anna University, India — Dr. Ramachandran Andimuthu, Faculty/ ANNA UNIVERSITY, India

The data on some of the climate sensitive infectious diseases have been assessed to understand the conducive ranges of temperature and relative humidity for each of these diseases.

Exploring the Health Effects of a Subtly Changing Climate: Risk and Vulnerability to Ross River Virus in Tasmania, Australia

Dr Anna Lyth, University of Tasmania and University of the Sunshine Coast (USC), Australia — Assoc. Prof. Neil Holbrook, University of Tasmania, Australia

This paper discusses a regional investigation of vulnerability to the mosquito-borne disease Ross River virus in Tasmania, Australia, where climate change effects are likely to be relatively subtle.

Thermal-induced Pavement Buckling in Heatwaves

Prof. Mark Bradford, The University of New South Wales, Australia

This study presents results of scientific modelling of upheaval buckling of concrete pavements subjected to elevated temperatures, as occurs in heatwaves. Buckling compromises safe travel and is being reported increasingly.

Scientific Evidence

Spatio-temporal Trends in Rainfall Variability and the El Niño Southern Oscillation in Mauritius

Caroline G. Staub, University of Florida, USA — Peter R. Waylen, University of Florida, USA

Annual precipitation totals in Mauritius are used to characterize the spatial and temporal variability of annual precipitation patterns and their response to underlying regional and global forcings from 1915-2009.