Erica Goode’s recent article in the New York Times (NYT – March 15, 2013), “Focusing on Violence Before It Happens,” describes a growing effort to identify and prevent major catastrophic events such as school violence. Two paragraphs from the article summarize the issue:

The young men had been brought to the attention of the School Threat Assessment Response Team program overseen by Dr. Beliz, one of the most intensive efforts in the nation to identify the potential for school violence and take steps to prevent it. The program, an unusual collaboration involving county mental health professionals, law enforcement agencies and schools, was developed by the Los Angeles Police Department in 2007, after the shooting rampage at Virginia Tech University, and was taken countywide in 2009 by Dr. Beliz, a deputy director of the mental health department.

In the national debate that has followed the killings at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, much of the focus has been on regulating firearms. But many law enforcement and mental health experts believe that developing comprehensive approaches to prevention is equally important. In many cases, they note, the perpetrators of such violence are troubled young people who have signaled their distress to others and who might have been stopped had they received appropriate help.

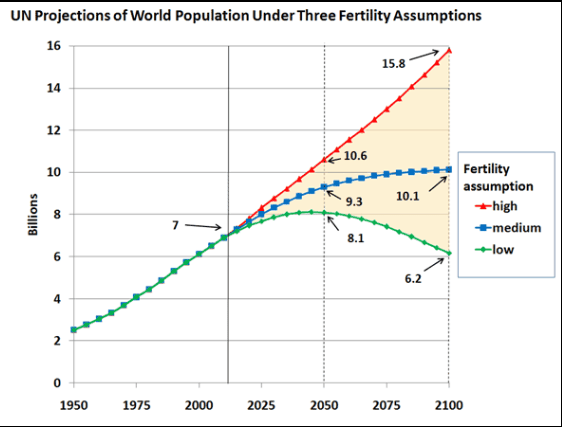

The government in the US is now starting to believe that by paying attention to warning signs, properly trained professionals can help prevent or mitigate disasters before they reach their catastrophic tipping points. The logical next step is to adopt the same preventative approach to the planetary tipping points that we predict will result from human caused (anthropogenic) climate change.

I have described climate change tipping points in previous blogs (June 25, 2012 and January 21, April 9, 16, 2013). My April 9 blog describes tipping points in the following way:

In a recent survey in Science magazine (Marten Scheffer et al. (11 co-authors) – Science – 19 October 2012, Vol 338, p. 344), Tipping Point was defined as a “Catastrophic Bifurcation,” a term which was taken from mathematical Chaos Theory, and has its own well developed definition. Bifurcation indicates a splitting into two branches; the “fork” in the title of both my book and this blog, refers to the same phenomenon. Tipping Points are predictable, an aspect that attracts a great deal of interest for obvious reasons. The financial markets have seen intense activity in this area (see James Owen Weatherall’s The Physics of Wall Street, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2013), with attempts to predict upcoming financial bubbles. The main premise behind the ability to predict bifurcation is that one monitors the driving forces that tend to restore a system to its state of equilibrium. As the system approaches the tipping point, these restoring forces tend to decrease until they completely disappear.

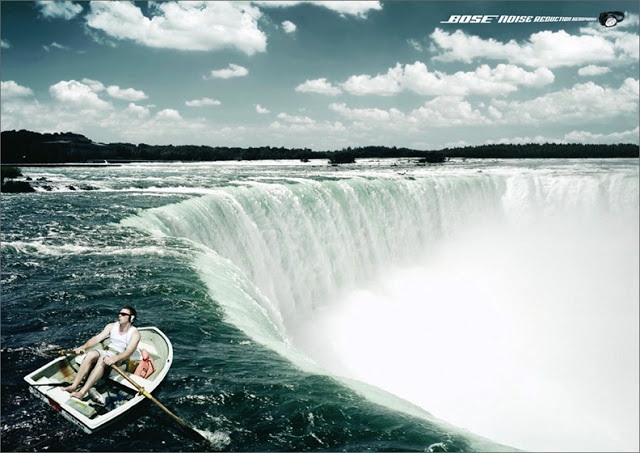

An image can do wonders to illustrate a concept, and this one accurately depicts our collective reaction to climate change.

I found this image (through Google Image Search) on a blog that illustrates and analyzes various advertising concepts. This ad for Bose sound cancellation headphones asserts that they are powerful enough to prevent the guy from hearing the approaching waterfall (Bose strongly advises not trying their product in these settings).

We can anticipate a waterfall long before we reach it, due to the noise and the strong prevailing currents. In fact, we can usually detect the signs early enough to row toward shore and prevent the fall that would be inevitable were we to keep a steady course. If, however, we ignore the warnings, or are ignorant enough not to recognize them, we pay the price. This holds true for collectives as well as individuals.

For a physicist, projecting individuals’ destructive tipping points seems a much more imprecise exercise than doing so for the global tipping points of the physical environment. At least in the latter case, the projections are based on well-defined, if not always fully understood, mechanisms. But as a country, after seeing the immediate effects of violence on our youths, we are willing to take chances and make the effort to implement such assessments because even one clear success might be worth it. Applying the same spirit to planetary tipping points has the potential to save many, many more children in the long run.

Am I Talking Out of Both Sides of My Mouth?

Last week’s blog was dedicated to Jim Hansen’s retirement and the central role that he has played in the Climate Change debate. It immediately garnered several comments from readers, none of which had anything to do with the blog.

All three comments focused on my personal life, referring to a local issue in which my wife played a major role, while I played a relatively minor one. The impression I got from the comments was that the individuals were attempting to get to her through me. Since this is my blog, and I am also the moderator, I could have easily blocked these comments.

However, the comments raised a few issues that are relevant to the main focus of this blog, so I will try to address them here. Some of these issues are personal and some are more general.

Some history:

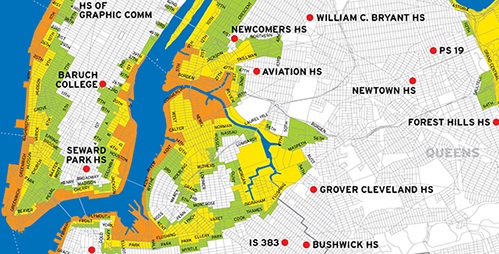

On June 2010, the City of New York decided to narrow a street (Prospect Park West, Brooklyn, NY) and construct a two-way protected bike lane, as shown below.

The city’s argument for the change was safety: the claim was that the multi-lane street caused speeding, which in turn led to traffic accidents. The street borders a large urban park (Prospect Park) that is already popular with bikers, especially during weekends.

The trend of replacing car lanes with bike lanes is not confined to New York City — it is global, and, almost everywhere, it triggers conflicts between car owners, bikers and pedestrians on how to share the common real estate. Two local organizations were formed to try to oppose the city’s change: “Neighbors for Better Bike Lanes” and “Seniors for Safety.” My wife is the president of the first organization and I am a member of the second. My wife and I happen to live in an apartment on the street in question, and our apartment was used to host a few of the meetings.

A common complaint raised in almost every such conflict – this one in Brooklyn being no exception – is that of a NIMBY (Not In My Back Yard) mentality. NIMBY, according to Wikipedia, is “a pejorative characterization of opposition by residents to a proposal for a new development because it is close to them, often with the connotation that such residents believe that the developments are needed in society, but should be further away.”

Reading through the recent comments on my blog, I found common theme was an accusation that I am talking out of both sides of my mouth – preaching for the need to take steps to minimize the impact of Climate Change, while at the same time, fighting to block them if such steps take place near where I live.

In 2010, I was teaching an honors course in my College that was related to Climate Change with an emphasis on students’ investigation of NIMBY phenomena in New York City. The product of the students’ investigation can be seen at http://macaulay.cuny.edu/eportfolios/tomkiewiczs11/.

As part of this course, I wanted to discuss the bike lane and try to figure out if such struggles can be classified as NIMBY. I wanted to invite my wife and the head of the local biking organization that was supporting the change to talk to the class. I couldn’t do it because the issue was litigated but I tried to address the issue through data analysis that included publicly available data that were collected by the pro-bikers group. The main question that I wanted to address with the class was whether or not this was an environmental issue in the first place. The city never claimed that it was an environmental issue; they claimed that this was a safety issue. Safety issues need to be backed by data. According to the groups that oppose the move, the data were not there. An environmental assessment of the move was never performed. If use was supposed, as the comments claim, to lower carbon footprints – there were strong arguments that it might achieve the opposite.

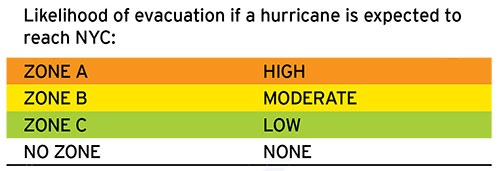

In terms of carbon footprints, NYC is one of the most sustainable cities in the United States. A recent inventory of NYC greenhouse gases is shown below:

About 75% of NYC’s total emissions come from buildings, with another 22% coming from transportation. Among NYC’s commuters, 55% use public transportation. In fact, 54% of households are without cars and 10% of residents walk to work. The relative contribution from bikes is rather small in this area. Also, most of the bikers that use this bike lane are recreational bikers – not commuters.

Surprisingly, slowing traffic speed to below the average of 30 mph (the speed limit in residential streets in NYC), actually increases gas consumption by about 30%.

Analysis of the environmental impact of such a change doesn’t stand up to scrutiny, thus making it difficult to characterize this issue as a NIMBY issue. As a safety issue, on the other hand, is a completely local issue that needs to be supported by data. The main argument in this debate is that the data do not support the claim. NIMBYism is a major obstacle for policy implementation of steps that are designed to mitigate impacts. I did discuss many aspects of this in previous blogs (June 18, July and August 27 – 2012), but this doesn’t mean that conflicts between local communities and government should be avoided. The constant scrutiny is beneficial and actions that impact communities need to be supported by data and the data should withstand scrutiny.

Now that I have addressed this issue, I hope that my little fight over a road near my apartment will disappear as a topic from this blog. It doesn’t belong here.