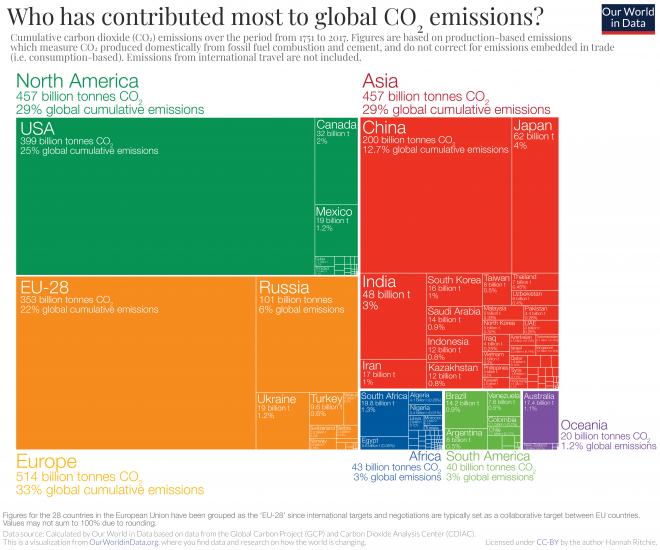

Figures 1 and 2 show the countries and US states most affected by climate change. This blog is focused on the criteria that are used for this ranking, while the next blog will focus on some of the list’s immediate consequences.

Figure 1 – The 10 countries most threatened by climate change in the 21st century (Source: IRC via Iberdrola)

Figure 1 – The 10 countries most threatened by climate change in the 21st century (Source: IRC via Iberdrola)

The link below Figure 1 defines and describes the background of the countries’ rankings, as defined during the COP27 meeting. Defining these vulnerabilities was both difficult and controversial, as summarized in the paragraph below:

The vulnerability criteria provoked controversy between one side, consisting of China and emerging countries, and the other, consisting of the European Union. The problem stemmed from what was considered vulnerable to the effects of climate change and therefore who should receive support from the international community. Because of this debate, it is necessary to investigate which countries are most likely to be affected in the event of a climate disaster, with no chance of recovery. Cases such as the United States or Australia, where phenomena usually cause adverse effects, but because they are countries that have the capacity to respond, are ruled out by studies related to vulnerability.

Per definition, the most vulnerable countries are developing countries that have no means of mitigating the inflicted damage. Details about the specifics of the vulnerabilities of these countries can be found in the original publication.

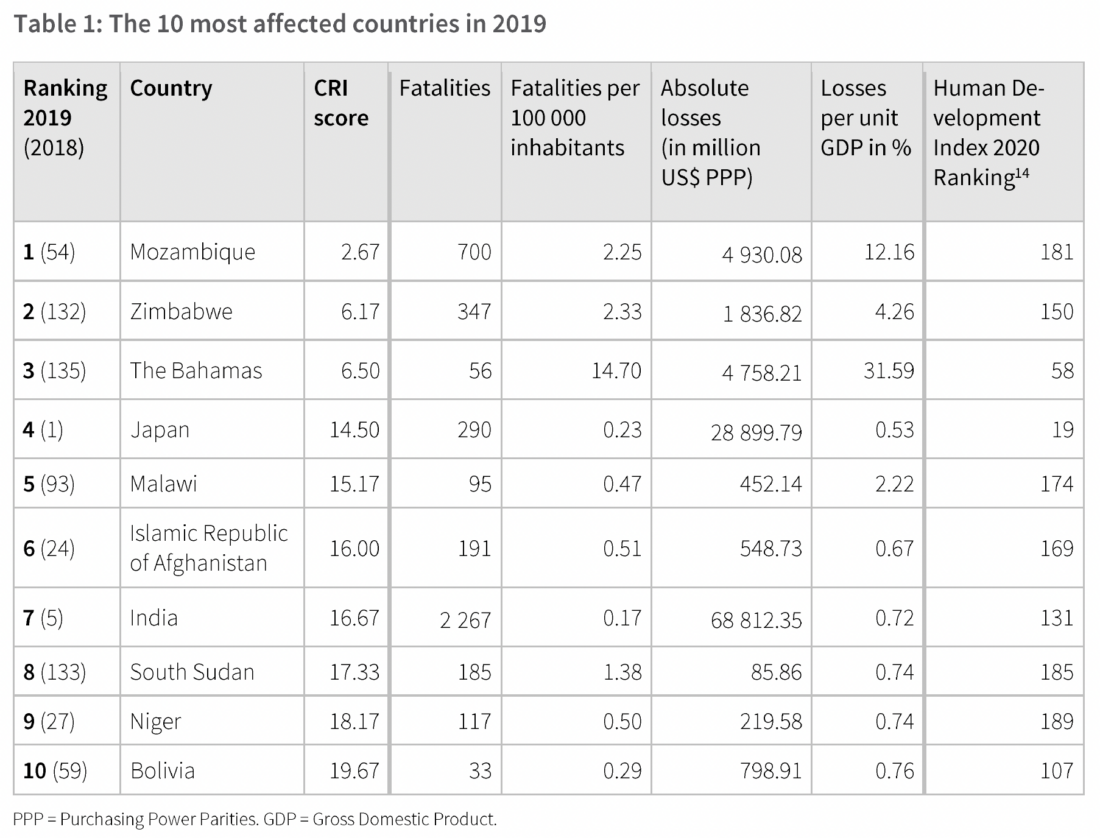

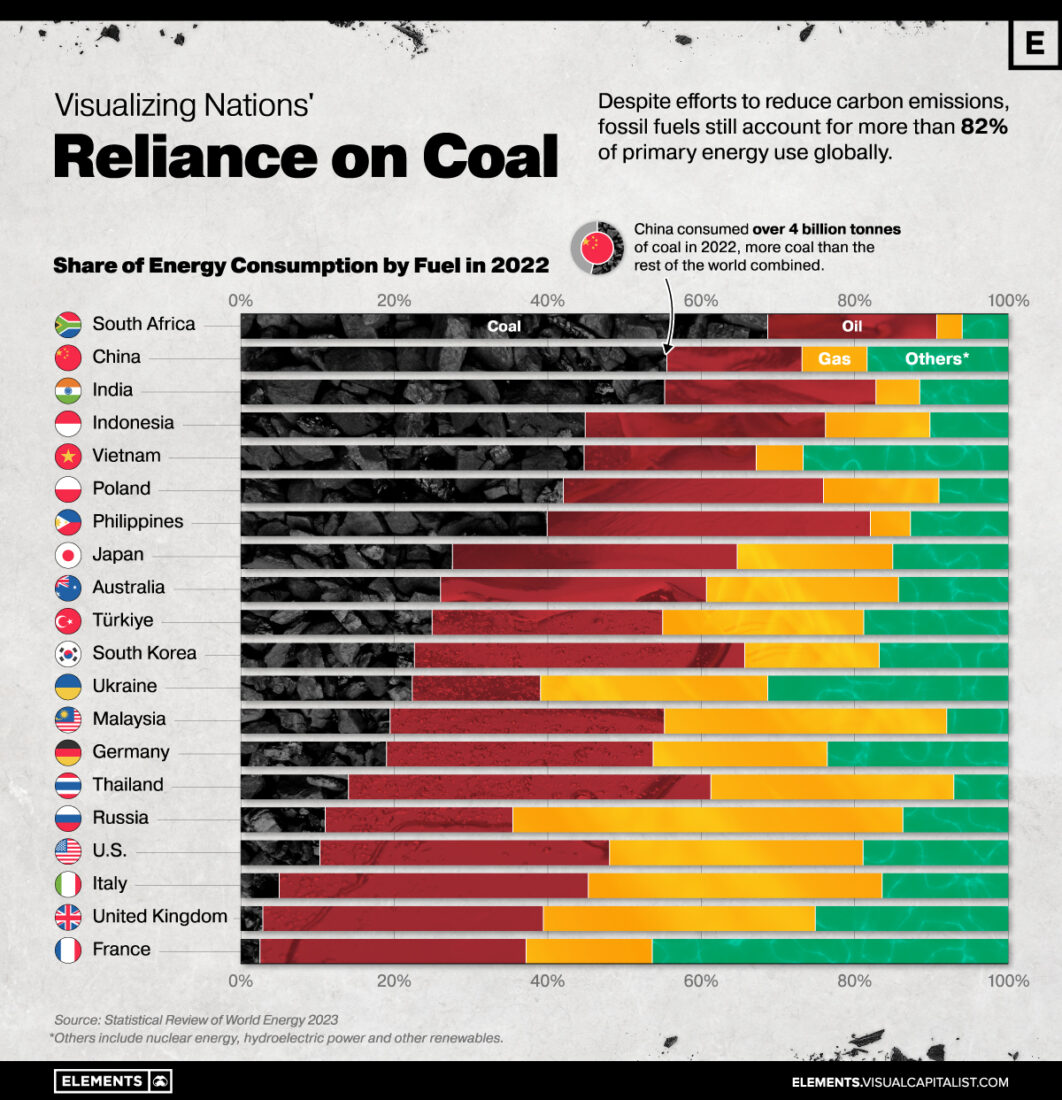

An alternative list of the most affected countries is given by Germanwatch and is summarized in Table 1:

This ranking is independent of the ability to mitigate the damage, but with one exception (Japan) also includes only developing countries. This ranking is based on the Global Climate Risk Index (CRI), summarized below from the Germanwatch Global Climate Risk Index 2020:

This ranking is independent of the ability to mitigate the damage, but with one exception (Japan) also includes only developing countries. This ranking is based on the Global Climate Risk Index (CRI), summarized below from the Germanwatch Global Climate Risk Index 2020:

The Global Climate Risk Index (CRI) developed by Germanwatch analyses quantified impacts of extreme weather events9 – both in terms of fatalities as well as economic losses that occurred – based on data from the Munich Re NatCatSERVICE, which is considered worldwide as one of the most reliable and complete databases on this matter. The CRI examines both absolute and relative impacts to create an average ranking of countries in four indicating categories, with a stronger emphasis on the relative indicators (see chapter “Methodological Remarks” for further details on the calculation). The countries ranking highest (figuring in the “Bottom 10”10) are the ones most impacted and should consider the CRI as a warning sign that they are at risk of either frequent events or rare, but extraordinary catastrophes.

The CRI does not provide an all-encompassing analysis of the risks of anthropogenic climate change, but should be seen as just one analysis explaining countries’ exposure and vulnerability to climate-related risks based on the most reliable quantified data available – alongside other analyses. 11 It is based on the current and past climate variability and – to the extent that climate change has already left its footprint on climate variability over the last 20 years – also on climate change.

Another ranking in the same publication is focused on long-term climate risk. The 10 most vulnerable countries in that list are also developing countries.

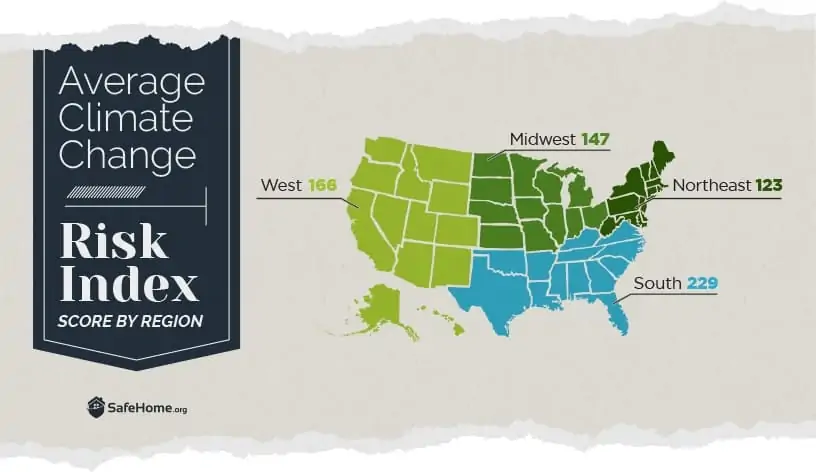

Figure 2 – Map of US states average climate change risk index score by region

(Source: SafeHome.org)

The methodology used in drafting Figure 2 is summarized at the end of the original article on SafeHome.org and is quoted below:

All of the data used in our analysis came from the excellent work of Climate Central and a site it maintains, States at Risk, which is a clearinghouse of data and analysis related to the impacts of climate change on the states. We excluded Alaska and Hawaii from our analysis because not enough data was available for either one to draw fair comparisons.

The site lists dozens of impacts for states and, often, multiple cities within the states, but the factors we included in our Climate Change Risk Index were:

- Increased mosquito season days, 1980s to today

- Dangerously hot days by 2050 (days with heat index of at least 105 degrees) in state or largest city

- Percentage of people vulnerable to extreme heat

- Increase in severity of widespread summer drought, 2000-2050

- Percentage of people currently affected by inland flooding (percentage living in 100-year floodplain)

- Increase in days with high wildfire potential, 2000-2050

- Percentage of population at elevated wildfire risk

- Percentage of people currently affected by coastal flooding (percentage living in 100-year coastal floodplain)

The data for each state was ranked from best to worst, and each state’s rank in all the categories were added together to create the overall ranking in which lower scores equate to lower risk from climate change.

The approaching “judgments” of these vulnerabilities will be discussed in the next blog. In a series of blogs that started on September 12th and ended on October 3rd, I focused on related issues such as developed countries’ commitments to mitigate their climate change losses and insurance companies’ adaptations to the selective vulnerabilities and losses brought about by climate change. I had to interrupt that series with a few blogs specific to academic institutions to help my students contribute to the discussions of these issues. With this blog and a few continuing blogs, I will return to the issue of global vulnerabilities.

Figure 1 – A subway ad for for CUNY highlighting different clubs

Figure 1 – A subway ad for for CUNY highlighting different clubs Figure 2 – Another subway ad specifies the number of programs that CUNY runs

Figure 2 – Another subway ad specifies the number of programs that CUNY runs (Source: ABC News: Andie Noonan via

(Source: ABC News: Andie Noonan via

(Source:

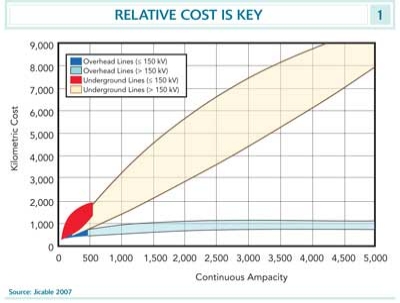

(Source:  Figure 1 – Above-ground high-power lines in the Netherlands

Figure 1 – Above-ground high-power lines in the Netherlands