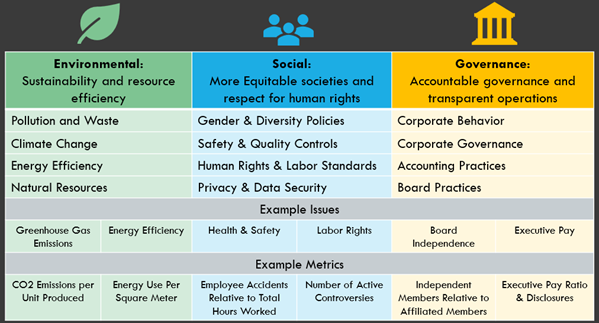

My last blog finished with a promise that this blog would propose ways to incorporate attempts to understand accelerated global changes into the strategic plans of local schools. Again, I will focus on my school. These changes include:

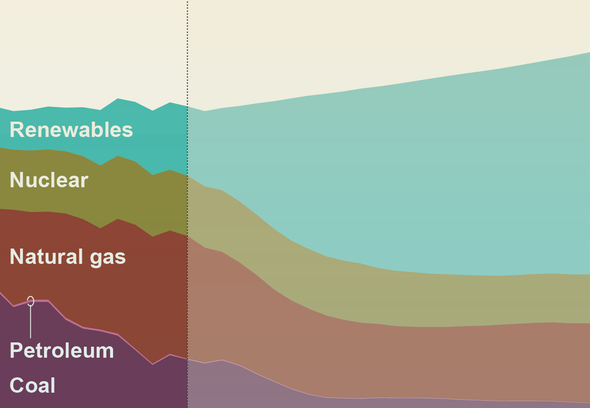

Mandated decarbonization

Mandated decrease in the use of single-use plastics

Testing of sewage for early detection of viral threats

Running schools with decreased enrollments

Preparing society for adaptation to extreme conditions.

Various aspects of these changes have served as the main topics for the more than 600 blogs I have posted over the last 11 years. Our students will spend their lives under such reality changes and our main job is to prepare them to function under such conditions. Every school’s strategic plan should be clear about the way that the school is trying to accomplish such a task.

It should be fully understood that global changes such as these require research to understand, adapt to, and mitigate the most damaging effects. School faculty usually cannot draw from their own experiences, whether direct or learned in school, to confront such changes but they are hired to teach their students how to function under such changing environments. All of this means that the accumulated knowledge has to come from research. Global changes such as these never take place simultaneously everywhere. The best way to learn how to function under such changes is to study places where these changing conditions hit hardest and early so feedback to action can also be generated early and analyzed.

As I mentioned earlier, CUNY is a federated university (see the May 17, 2023 blog, part 3 in this series) that covers 25 institutions (11 four-year colleges, 7 community colleges, and 7 graduate/professional schools) and a central administration. Adaptations that reflect the accelerating global changes are compatible with President Abraham Lincoln’s original creation of large-scale, state-based higher education in the form of land-grant universities:

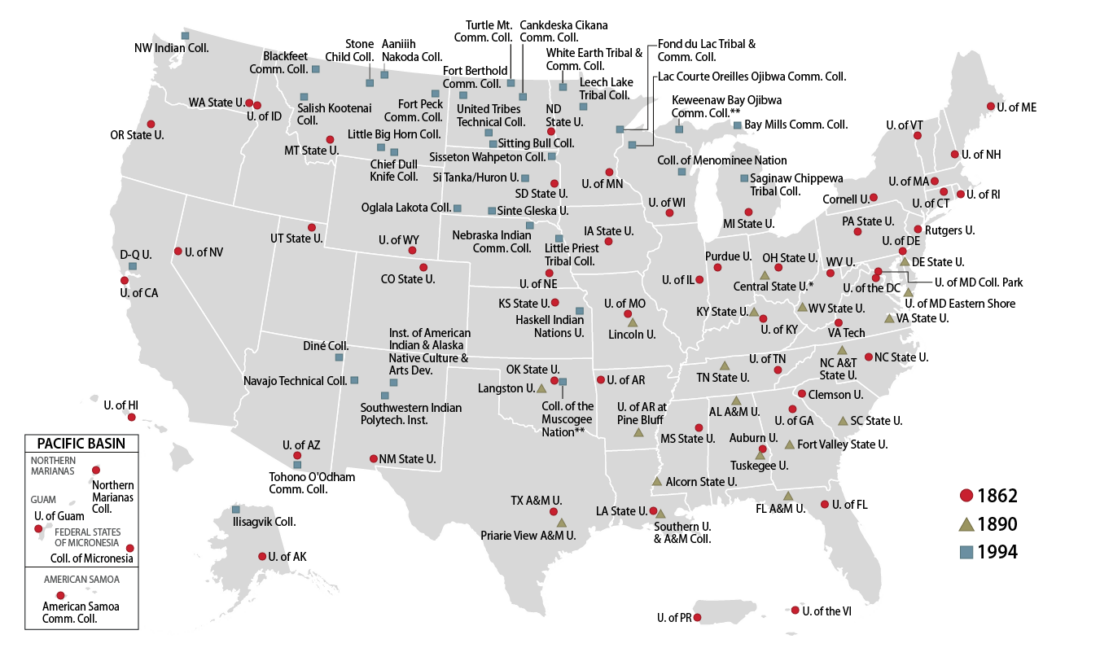

A land-grant university (also called land-grant college or land-grant institution) is an institution of higher education in the United States designated by a state to receive the benefits of the Morrill Acts of 1862 and 1890.[1]

Signed by Abraham Lincoln in 1862, the first Morrill Act began to fund educational institutions by granting federally controlled land to the states for them to sell, to raise funds, to establish and endow “land-grant” colleges. The mission of these institutions as set forth in the 1862 act is to focus on the teaching of practical agriculture, science, military science, and engineering—although “without excluding other scientific and classical studies”—as a response to the industrial revolution and changing social class.[2][3] This mission was in contrast to the historic practice of higher education concentrating on a liberal arts curriculum. A 1994 expansion gave land-grant status to several tribal colleges and universities.[4]

Ultimately, most land-grant colleges became large public universities that today offer a full spectrum of educational opportunities. However, some land-grant colleges are private, including Cornell University, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), and Tuskegee University.[5]

The key sentence of this introductory paragraph is that which clarifies that the institutions were meant to teach multiple topics—both “practical” and those relating to science and classical studies. At that time, the US reality was dominated by land and agriculture. Now it is changing quickly, as a result of anthropogenic (human-triggered) dominance. The need to adapt to the changing reality is the same. New universities need not be created but their curricula need to be changed to accommodate.

Figure 1 –The Land-Grant Universities in the US (Source: EveryCRSReport.com)

Back to the BC Strategic Plan. Aside from the creation of the Cancer Institute, the present strategic plan does not mention research content. However, this strategic plan is about to expire, to be replaced by a new one. I have no idea what shape the new plan will take, but I can hope and make suggestions.

CUNY has the advantage of being a multi-institutional organization with strong centralized governance. A few of the largest changes that need to be accommodated, such as timely decarbonization of energy use and decrease of single-use plastic, are mandated by the State and City governments. The university is now working on them and I am involved in this work.

These efforts are coordinated by the CUNY Central Sustainability Office (Sustainable CUNY, see June 4, 2019). To implement changes, the office invites representatives from each of the institutes to analyze issues and make recommendations. Usually, the results are not mandated by the central office. Rather, we see them as announcements from individual colleges that they are creating pilot projects. The colleges work with the central office to draft timelines and deliverables for the projects. The results are analyzed on a timely basis to decide if, how, and when, to extend these pilots to the entire university. Once this takes place, the changes become mandated.

These dynamics can be explicitly stated in the strategic plan.

Incorporating decarbonization of energy use and reducing the use of single-use plastic are both relatively simple, mandated changes. The pilot steps taken require feasibility and economic analyses but not scientific breakthroughs. Water stress and other calamities that result from climate change feedback can bring a major need for adaptations, in which new technology might be required. Here, we might take advantage of the federated structure of the country that we live in.

As I mentioned earlier, accelerated global changes do not hit either this country or the world uniformly. A good example is the impact of climate change on the water cycle.

Up to now, NYC, the place where I live and work, has hardly been impacted. The Southwest, where Sonya Landau, my friend, and the editor of this blog (June 22, 2021) lives, is already suffering temperatures in the upper 90s(oF) temperature and a multi-year drought. The region is now in a race against accelerated climate change, seeking ways to be less dependent on fresh water. There is no question in almost anyone’s mind that the water stress will expand to hit every corner of the world. The two recent references below will provide some background:

NYT Op-Ed: When One Almond Gulps 3.2 Gallons of Water

NPR: Arizona farmers rely on drought-stricken Colorado River to water crops

We all should be prepared—especially our students. We can strive to expand our boundaries and collaborate with schools in other areas to allow our students to do relevant research on these issues.

Next week’s blog will continue exploring the same line of thinking and will include experiences of College as a Lab and collaboration with local industry on college campuses.

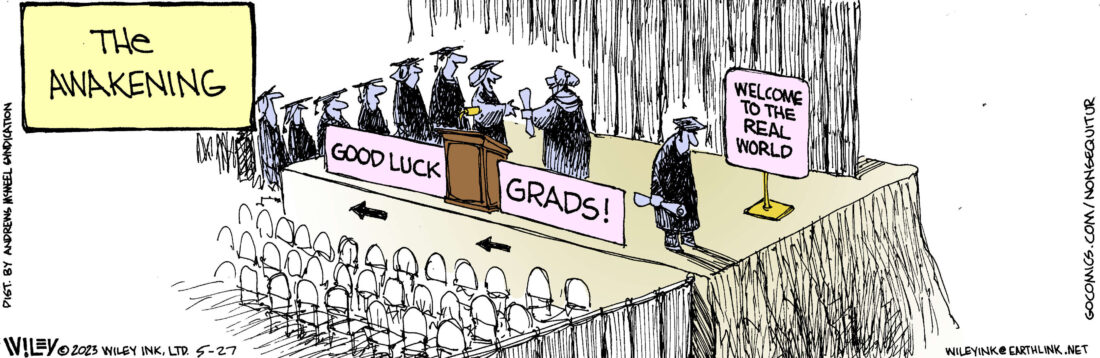

The picture above was taken from my favorite T-shirt, which features my favorite quote. It is also the main reason that I chose an academic career: to get a license to experiment. When I wear the shirt, it often triggers mixed responses despite Einstein’s name on the bottom. Often, people argue that there is a world of difference between not knowing what we are doing and investigating the unknown. From my perspective, regardless of interpretation, the quote strongly encourages experimentation with full knowledge that there is a high probability that most of the experiments will fail.

The picture above was taken from my favorite T-shirt, which features my favorite quote. It is also the main reason that I chose an academic career: to get a license to experiment. When I wear the shirt, it often triggers mixed responses despite Einstein’s name on the bottom. Often, people argue that there is a world of difference between not knowing what we are doing and investigating the unknown. From my perspective, regardless of interpretation, the quote strongly encourages experimentation with full knowledge that there is a high probability that most of the experiments will fail.

Spring Break at Brooklyn College

Spring Break at Brooklyn College