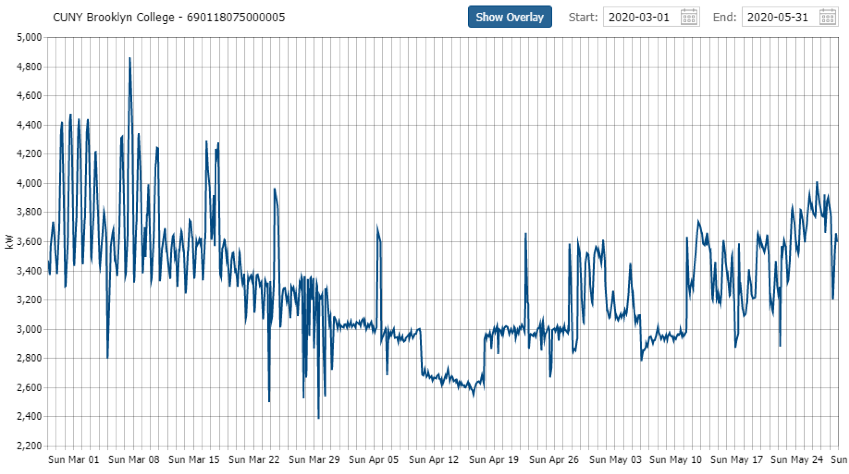

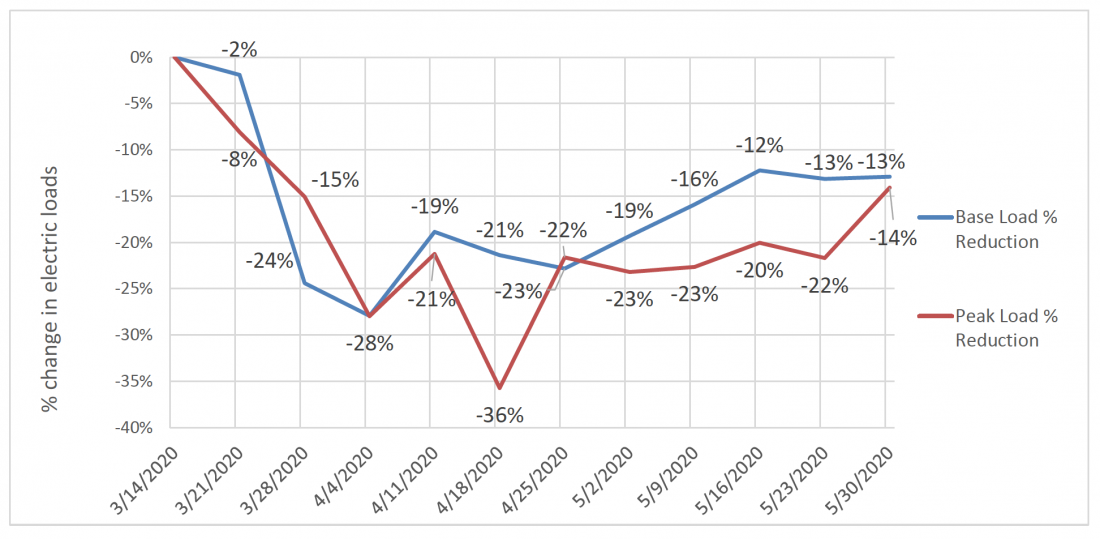

Last week I outlined my school’s effort to measure its energy use during the COVID-19 lockdown. As I mentioned there, I got the data following my (approved) visit to the campus. While I was there, I realized that even without students, faculty or staff, the campus is still using about 80% of our pre-COVID-19 energy. Our Director of Environmental Safety addressed my observations and said that the school is working to minimize energy use when possible. However, she said that this work is done building by building by maintenance staff.

I believe that all these adjustments (e.g. A/C, lights) can be done electronically (and remotely). By coordinating all such matters in one place, this remote management could be a giant step in mapping and accelerating our campus-mandated conversion to zero carbon emissions status by mid-century. It would also save money and serve as an opportunity for our students to practice applied energy transitions that they can replicate in other facilities after finishing school. In my view, it’s never a bad thing to provide our students with preparation for the post-graduation job market.

Meanwhile, given that our campuses are already closed, it makes sense to take this time to plan for future contingencies. In terms of energy use, we need to learn how to convert the campus from a passive energy user to a participant in the energy distribution and delivery processes. This goal mirrors one of the campus’ missions: encouraging application of learned concepts in the real world.

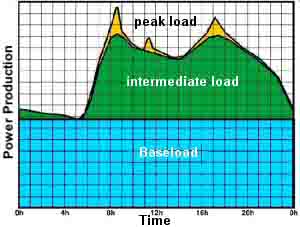

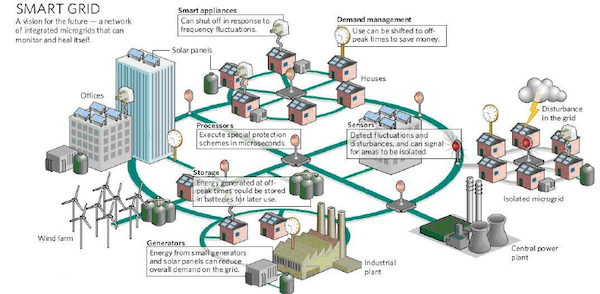

I have discussed the two main terms that describe energy distribution—smart grids and microgrids—before. The figure below shows microgrids integrated with a smart grid:

Schematic diagram of energy distributed through a smart grid and microgrids

National Renewal Energy Laboratory (NREL) defines a smart grid in this way:

[A] Smart grid is a nationwide concept to improve the efficiency and reliability of the U.S. electric power grid through reinforced infrastructure, sophisticated electronic sensors and controls, and two-way communications with consumers.

There are two parts to the smart grid concept:

- Strengthen the transmission and distribution system to better coordinate energy delivery into the grid.

- Better coordinate energy delivery into the grid and consumption at the user end.

Many large research campuses have already begun to build smart grids. Most operate electricity grids that include power generation; load control; and power import, distribution, and consumption. Because of their size and affiliation with electricity consumers on campus, plant managers often have better central management and greater opportunities to improve distribution and end-use efficiency than most electric utilities. Furthermore, most campuses already have two-way communications through interconnected building automation systems. Campus plant managers use these communications for energy management and load shedding, which are among the top goals of utility smart grid projects.

Ultimately, research campuses may play a central role in developing and testing smart grid concepts ultimately used to improve the national utility grids. The U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) is investing approximately $4 billion to encourage the development of smart grid technologies. More information regarding the demonstration projects can be located at the Smart Grid Projects website.

New York State, through its NYSERDA agency, is heavily involved in both research and some implementation of the concept. Here is an excerpt from my July 2, 2019 blog:

Other key issues, such as the “DG Hub,” were new to me; I needed some background:

The NY-Solar Smart Distributed Generation (DG) Hub is a comprehensive effort to develop a strategic pathway to a more resilient distributed energy system in New York that is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy and the State of New York. This DG Hub fact sheet provides information to installers, utilities, policy makers, and consumers on software communication requirements and capabilities for solar and storage (i.e. resilient PV) and microgrid systems that are capable of islanding for emergency power and providing on-grid services. For information on other aspects of the distributed generation market, please see the companion DG Hub fact sheets on resilient solar economics, policy, hardware, and a glossary of terms at: www.cuny.edu/DGHub.

I was particularly interested in a joint-published work by NREL (National Renewable Energy Laboratory) and CUNY, which offered a detailed analysis of the effectiveness of solar panel installations in three specific locations in New York. The paper included a quantitative analysis of the installations’ contributions to the resilience of power delivery in these locations. Below is a list of the different models that they have tried to match to the locations. The emphasis here is on the methodology and what they are trying to do, not on the sites themselves. REopt is a modeling platform to which they try to fit the data:

CCNY (City College of New York), one of CUNY’s major campuses, has an important research presence in the effort:

The CUNY Smart Grid Interdependencies Laboratory (SGIL) at the City College of New York is a research group focused on: the rising interdependencies between the power grid and other critical infrastructures; power system resilience; microgrids; renewable energy; and electric vehicles. We use our expertise with power system fundamentals, control, operation and protection, as well as analytical and machine-learning based tools to contribute to the national call for a greener, more efficient, reliable and resilient power grid.

Microgrids are localized grids that can contribute to a main grid or a smart grid. They can also operate completely independently. Likewise, microgrids themselves can be “smart.” Thus, they might be an important initial contribution to electric power delivery to smart grids, adding resilience to that power delivery. Portland’s recent PGE effort makes a great example.

Microgrids are also contributing to Europe’s energy transition:

According to the new report, titled New Strategies For Smart Integrated Decentralised Energy Systems, by 2050 almost half of all EU households will produce renewable energy. Of these, more than a third will participate in a local energy community. In this context, the microgrid opportunity could be a game changer.

The report describes microgrids as the end result the combination of several technological trends, namely, rooftop solar, electric vehicles, heat pumps and batteries for storage. The key is that these technologies are decentralized—they can easily be owned by consumers and cooperatives in local systems.

A team at the University of Calgary in Canada is also developing mobile microgrids that can be used for safety and resiliency.

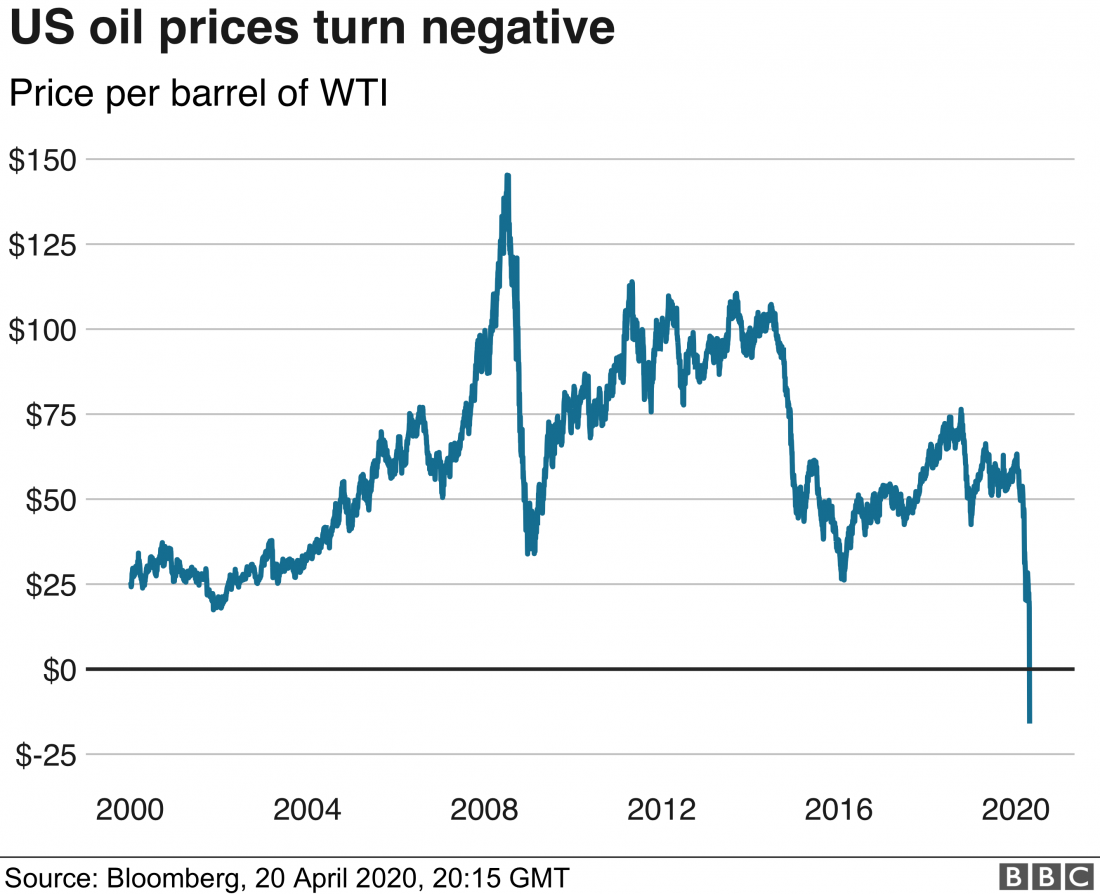

The other branch of an effective transition to more efficient energy use is obviously the change in source. We need to replace some of the conventional power sources with sustainable ones such as solar and wind. But these bring their own issues. Sustainable energy sources depend on the weather and the availability of light and wind. Nor does this variability coincide with the variability in energy usage. Given that weather is mostly unpredictable, it is vital that we synchronize weather and load.

Universities are the ideal places to experiment with these technologies before they reach the larger market. I’ll look into some examples soon.