A recent announcement from Facebook informed us all that “Connection is evolving so are we … welcome to Meta.”

While I was not born there, I grew up in Israel, so Hebrew is my “native” language. In Hebrew, “meta” refers to a dead female. Following this line of thinking, Facebook chose to describe itself as a dead female company. However, according to the Oxford Learner’s Dictionary, meta is an adjective: “(of a film, work of literature, art, etc.) showing awareness of itself or its genre.” Its synonym is “self-referential.” In this context, the company presents itself as a self-referential communicator of reality. I am paying attention.

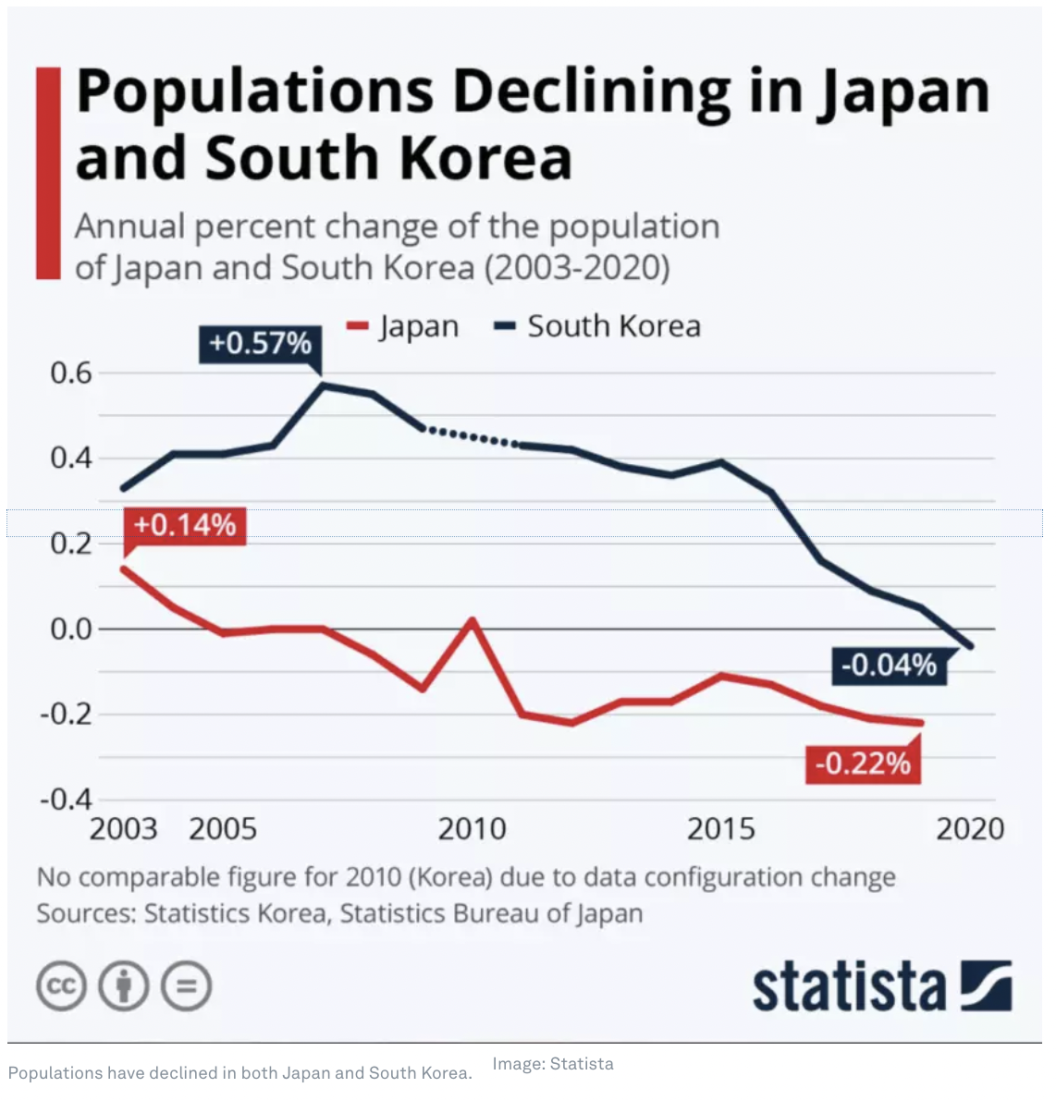

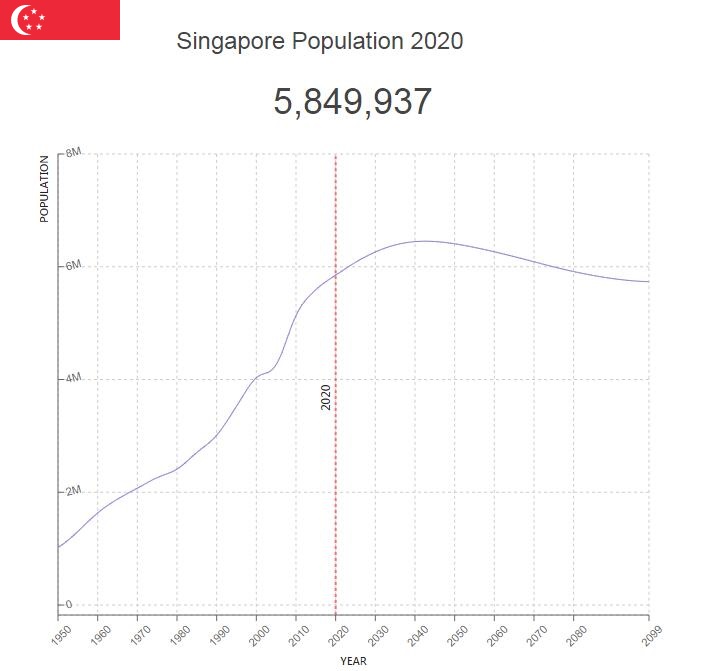

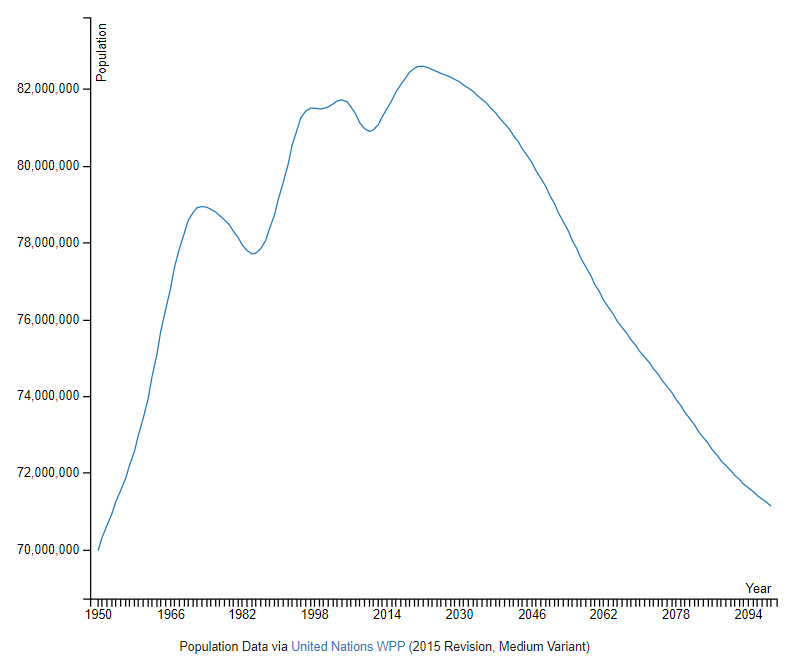

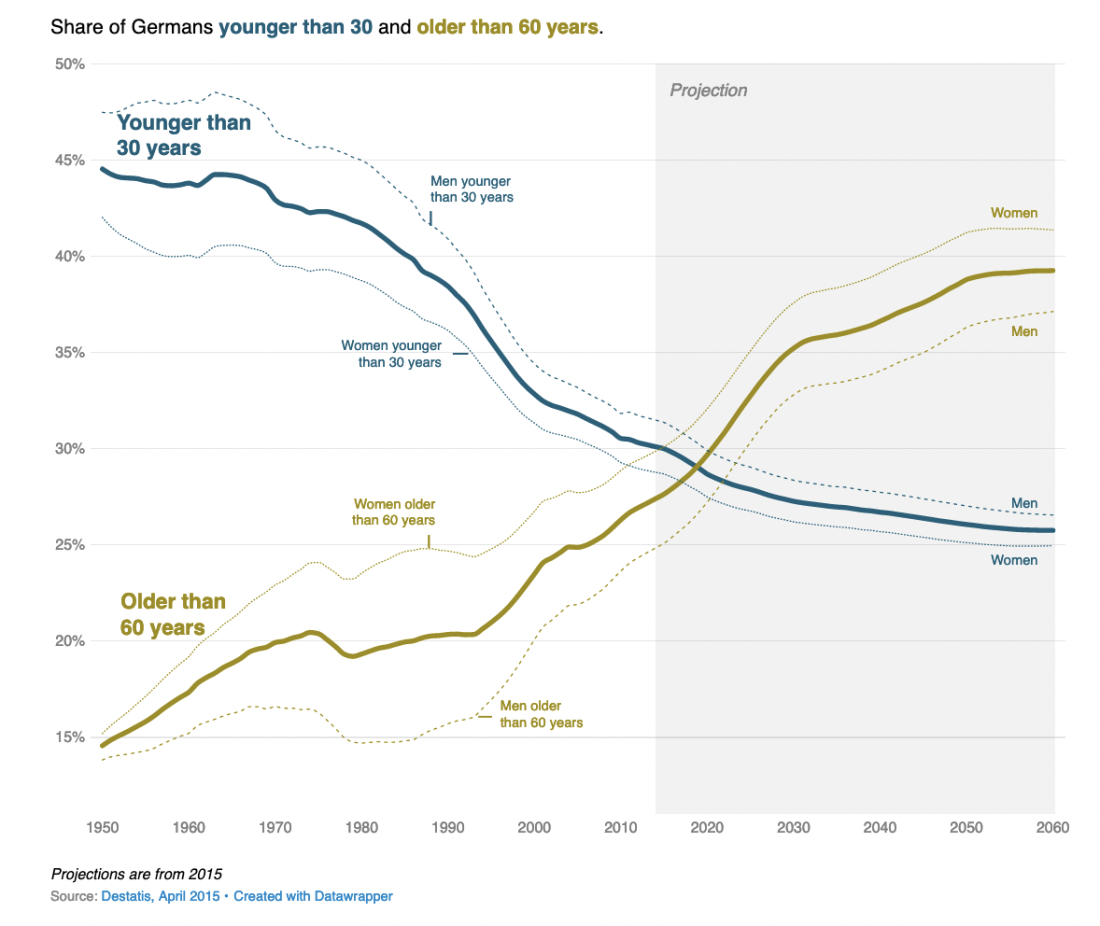

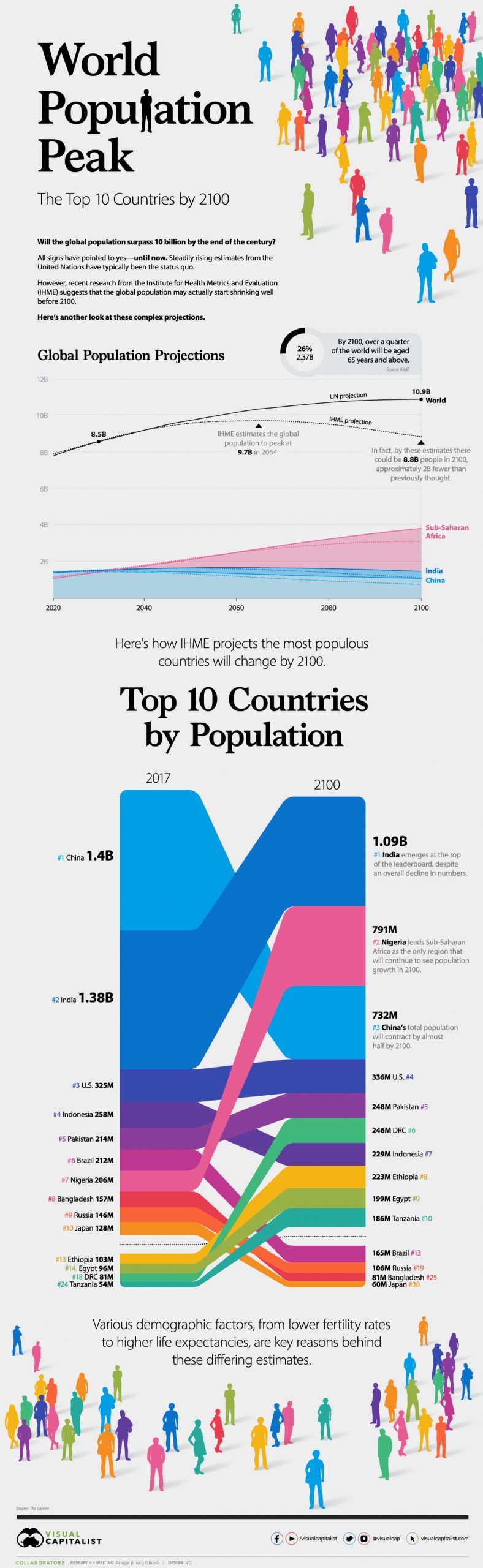

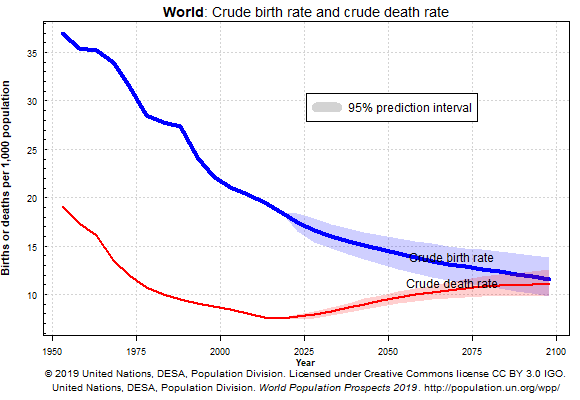

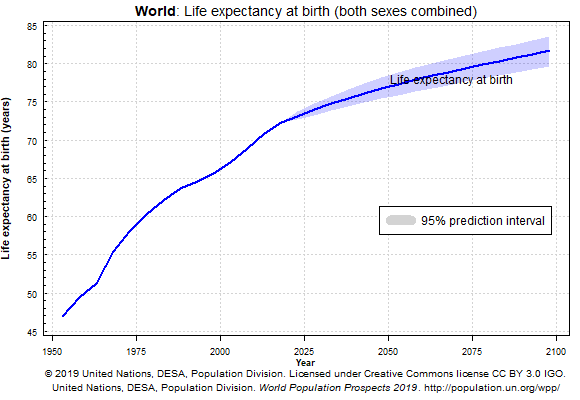

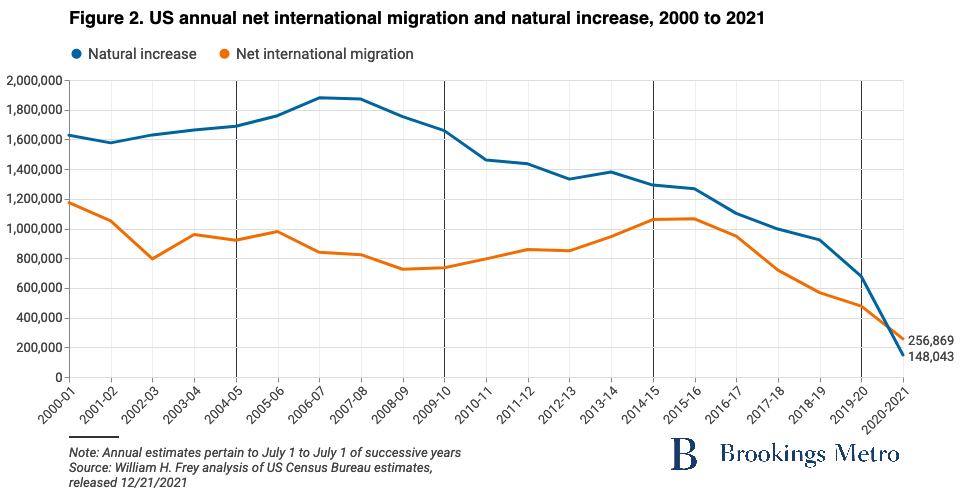

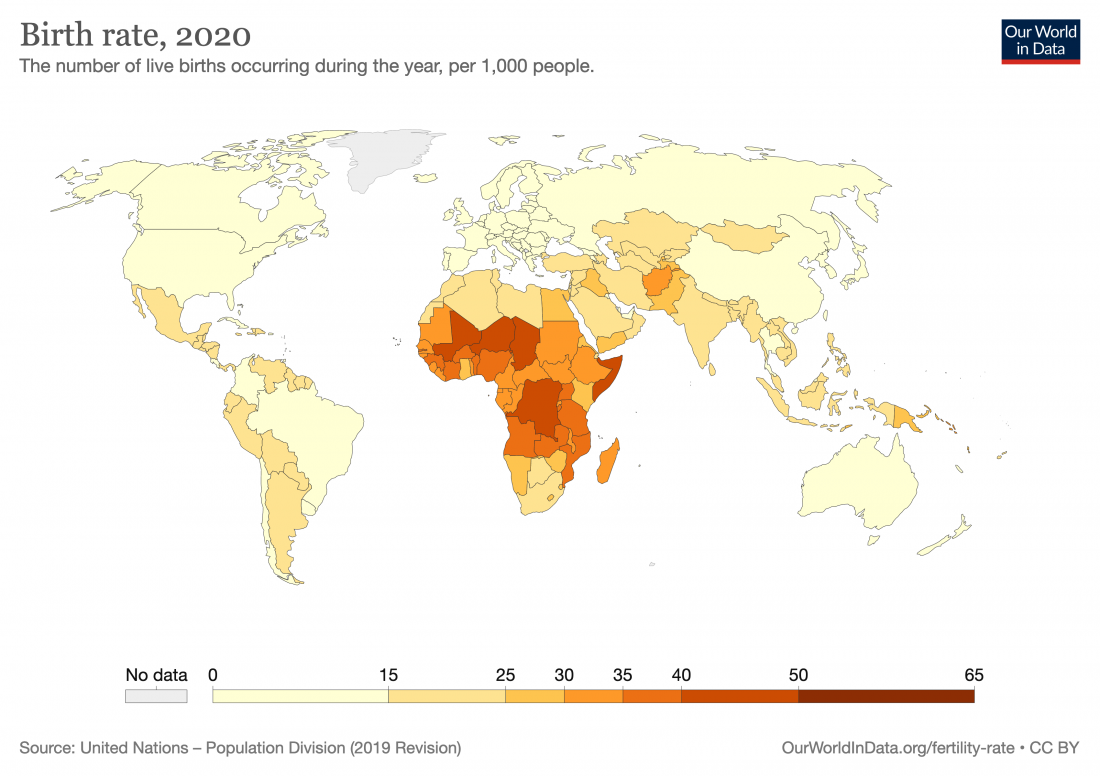

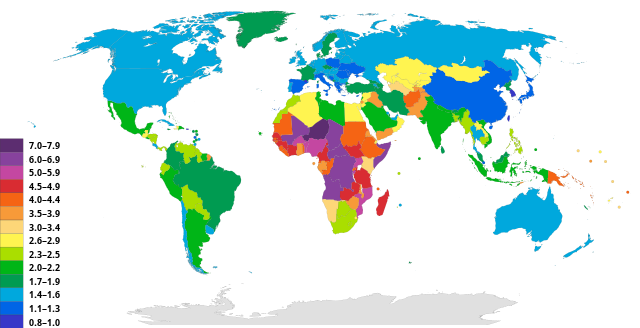

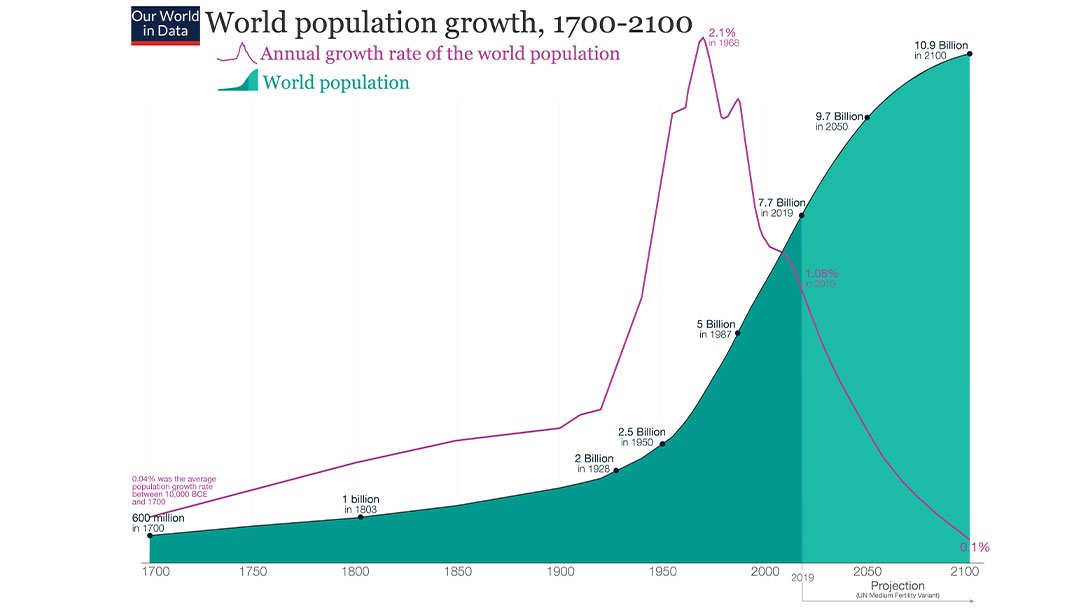

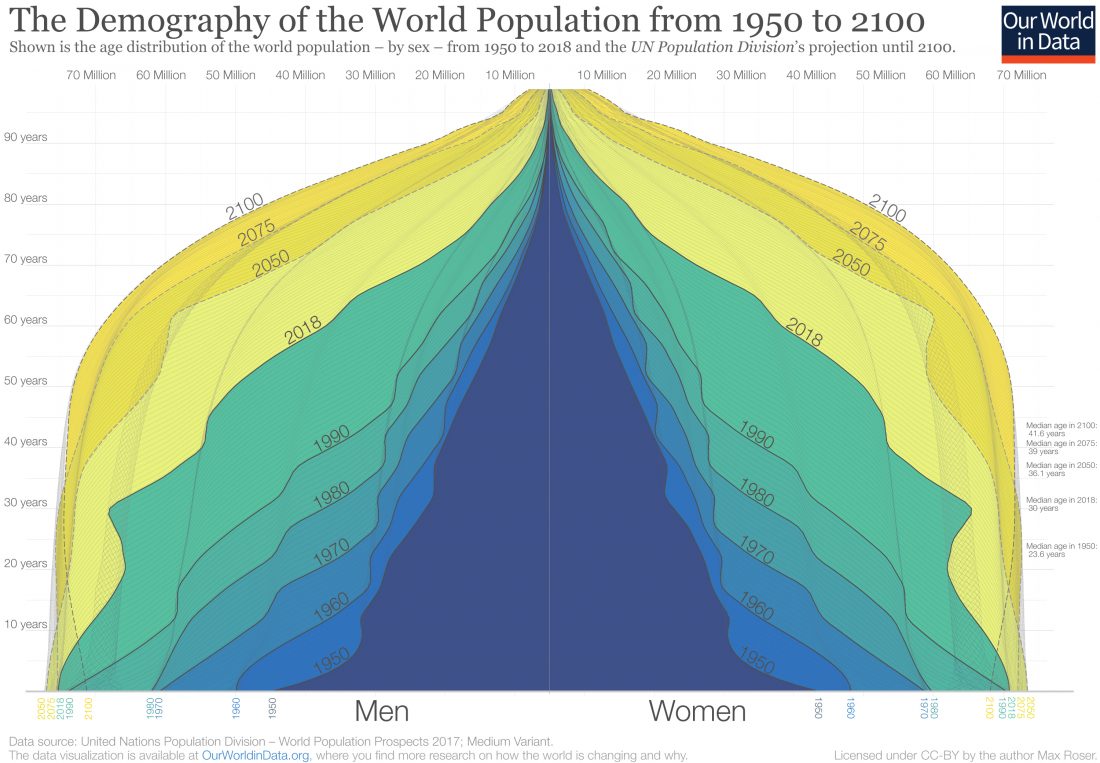

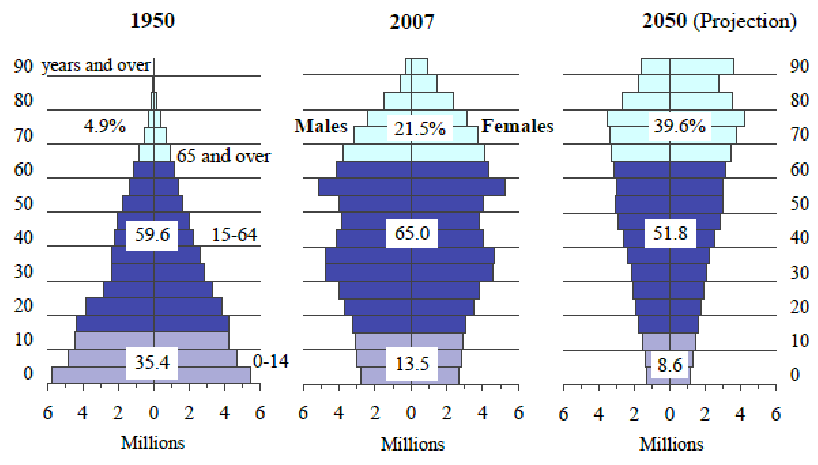

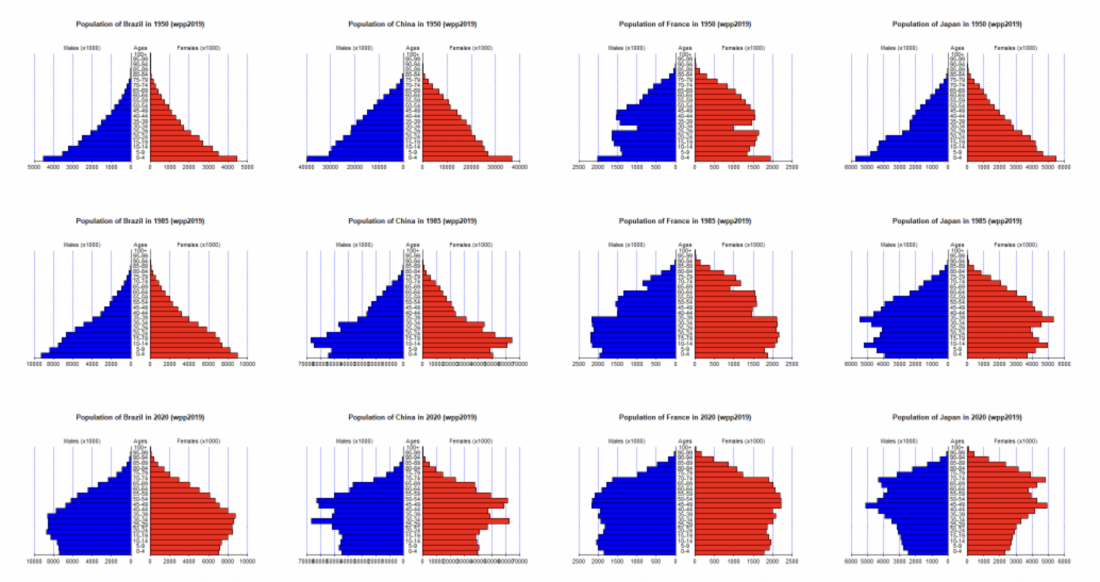

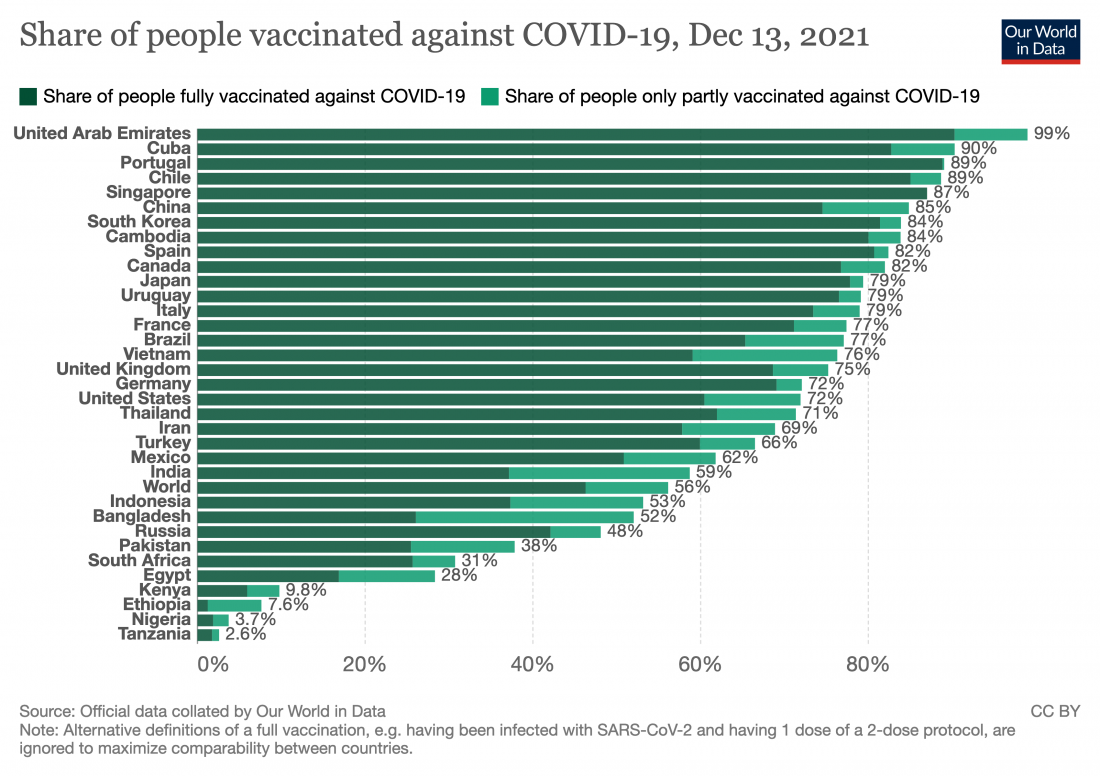

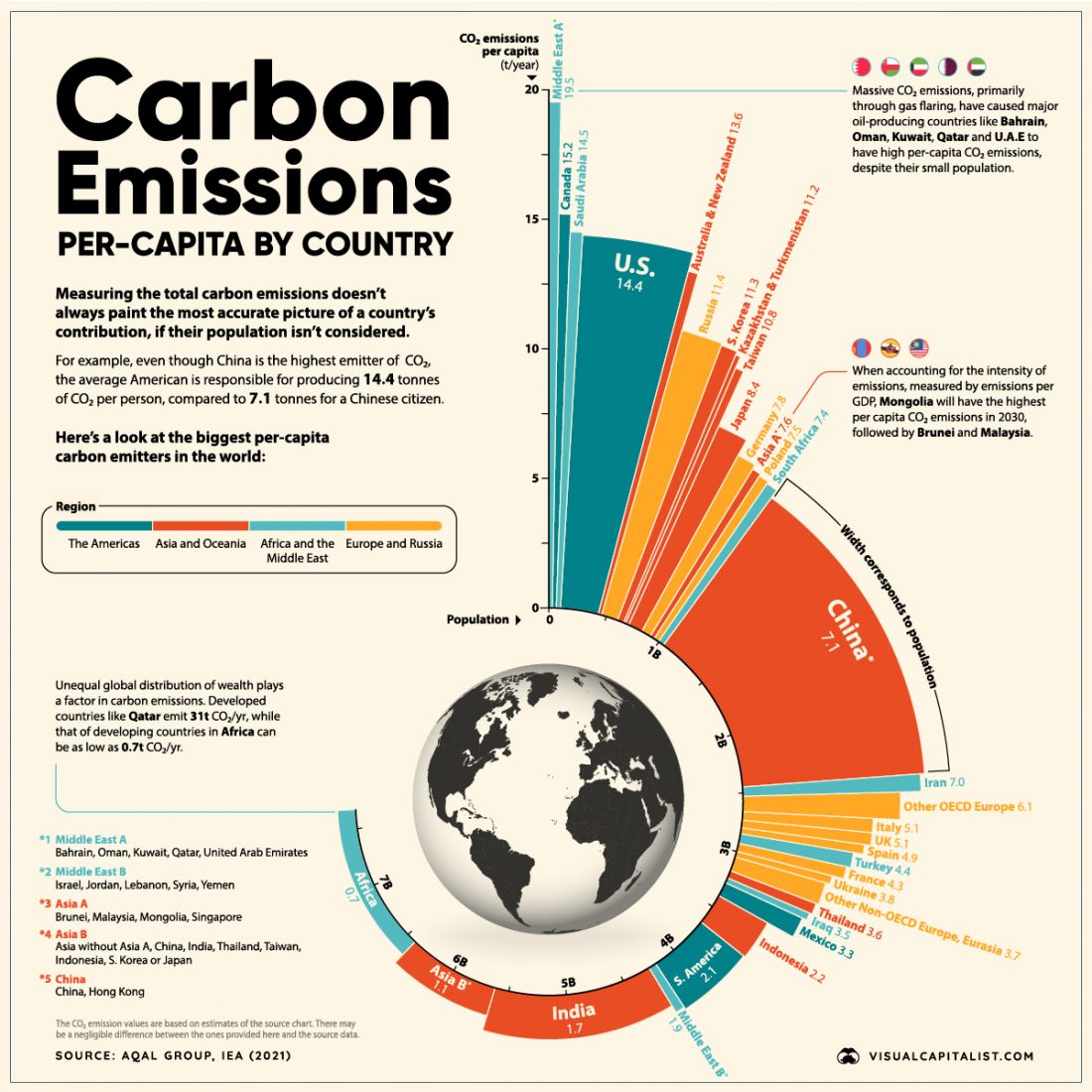

As I have often mentioned on this blog, I teach three courses at the undergraduate level: one on cosmology and two that focus on climate change. In these courses, I use reality to construct my syllabi. I have been using this blog to describe the three global transitions that we are now going through: the pandemic, climate change, and the shrinking global population. In both my teaching and my writing, my main objective is to help my students and readers make sense of the science that drives these transitions, using language that overcomes the need for prerequisites like traditional science courses.

One of these transitions, the COVID pandemic, is short-lived, with an end in sight (hopefully). The other two are projected to grow throughout the lifetime of my students (the “end of now” in my book on climate change).

I am trying to teach basic principles that will stay with the students (and everybody else) throughout all of these transitions and thus facilitate their adaptation to changes in their respective realities. The first thing that I am trying to share with you and my students is that while all of us are part of a collective reality, we each have biases that shape our own perception of reality. Some of these are shared biases, some are our own and come from our life experiences (see the November 21–28 2017 blogs on “Collective Irrationality and Individual Biases”).

From FunkyEnglish.com

When I present to my classes and this blog, I am in a position of some authority, so my biases hold some weight. This is probably more important for my students than my readers because they are dependent on my grading and often need recommendation letters to facilitate their entry into other parts of life. It is unavoidable that all of us: teachers, students, and readers, cherry-pick details and data that will enforce some of our biases. In the past, I have described such cherry-picking in terms of Godwin’s law for applying lessons from the Holocaust (January 19, 2021), the economic risks of climate change (December 24, 2019), and who is to blame for climate change (June 20, 2017). Wikipedia has an entry that describes the practice:

Cherry picking, suppressing evidence, or the fallacy of incomplete evidence is the act of pointing to individual cases or data that seem to confirm a particular position while ignoring a significant portion of related and similar cases or data that may contradict that position. Cherry picking may be committed intentionally or unintentionally.[1]

The term is based on the perceived process of harvesting fruit, such as cherries. The picker would be expected to select only the ripest and healthiest fruits. An observer who sees only the selected fruit may thus wrongly conclude that most, or even all, of the tree’s fruit is in a likewise good condition. This can also give a false impression of the quality of the fruit (since it is only a sample and is not a representative sample). A concept sometimes confused with cherry picking is the idea of gathering only the fruit that is easy to harvest, while ignoring other fruit that is higher up on the tree and thus more difficult to obtain (see low-hanging fruit).

Cherry picking has a negative connotation as the practice neglects, overlooks or directly suppresses evidence that could lead to a complete picture.

Cherry picking can be found in many logical fallacies. For example, the “fallacy of anecdotal evidence” tends to overlook large amounts of data in favor of that known personally, “selective use of evidence” rejects material unfavorable to an argument, while a false dichotomy picks only two options when more are available. Some scholars classify cherry-picking as a fallacy of selective attention, the most common example of which is the confirmation bias.[2] Cherry picking can refer to the selection of data or data sets so a study or survey will give desired, predictable results which may be misleading or even completely contrary to reality.[3]

A video of Rand Paul recently re-surfaced that demonstrates the danger of such misinformation.

None of us is completely free of bias; those few who strive for “objectivity” must understand their own while filtering through those of others. This burden falls not only on the teacher or writer but must also be shared with the students and readers. This is not an easy task, however. For students, most class material is new, making it very hard for them to identify cherry-picking and biases. It is, therefore, the responsibility of the educational system to come up with a methodology that enables students to do so. This is a researchable issue that falls under the more general field of communication. A 2017 study by Luke Lefebre, Leah Lefebre, and Dale Anderson looked at 47 communication centers within US universities and tracked the changing trends in their organization, operation, services, etc.

Such centers focus on the usual tools of communication, including writing and speaking, as well as the more recent platforms for digital communications, in which Meta features heavily. I haven’t done any research on this issue yet, so I have no idea what resources these centers have to investigate biases.

Biases used to play the smallest role in physical sciences, probably because the self was removed from these disciplines. This is no more.

In an earlier blog (February 2, 2021), I discussed the connection between physics and reality. Traditionally, physics has been taught as disconnected from humans; everything connected with humans fell under the disciplines of social studies, humanities, and art, as opposed to “physical” or “natural sciences.” Now, things are changing. At Brooklyn College, where I teach, they all fall under the School of Natural and Behavioral Sciences (NBS), which includes psychology, anthropology, kinesiology, and interdisciplinary studies such as climate change (see my December 28, 2021 blog on the latter).

There are attractive opportunities for detailed studies of the global transformations that are taking place in front of all our eyes: they offer to prepare students to be part of these transitions after they finish school. The government has imposed certain mandates aimed at adapting to these various transitions. In the same way that I discussed in my “Campus Transition into Sustainability Teaching Laboratory” blog (June 18, 2019), we can use these as laboratories through which to learn the fundamentals of the disciplines that we are trying to master.

In the US, much of the funding for government-supported research comes from the NSF (National Science Foundation). When academics are applying for funds to conduct original research—whether new teaching methodology or pure scientific research, they submit proposals, which are judged on two criteria:

- Intellectual Merit: The Intellectual Merit criterion encompasses the potential to advance knowledge.

- Broader Impacts: The Broader Impacts criterion encompasses the potential to benefit society and contribute to the achievement of specific, desired societal outcomes.

The structure of the NSF is based on directorates and it mostly reflects the disciplinary academic structure of the sciences. However, it is slowly changing and has added two new directorates to reflect the more general, interdisciplinary issues that society is now facing:

Directorate for Social Behavioral & Economic Sciences

SBE Office of Multidisciplinary Activities (SMA)

SBE’s Office of Multidisciplinary Activities supports interdisciplinary research and training in the social, behavioral, and economic sciences, including SBE’s intersections with other science and engineering fields.

Directorate for Education & Human Resources

Research on Learning in Formal and Informal Settings (DRL)

DRL invests in the improvement of STEM learning for people of all ages by promoting innovative research, development, and evaluation of learning and teaching across all STEM disciplines in formal and informal learning settings.

Undergraduate Education (DUE)

DUE’s programs are intended to strengthen STEM education at two- and four-year colleges and universities by improving curricula, instruction, laboratories, infrastructure, assessment, diversity of students and faculty, and collaborations.

The alternative to government-supported research on biases might return us to Meta (Facebook). The net worth of Meta is approaching $2 trillion. It might be worthwhile for the company to support self-centered communication as a business expense.