Like many others, I watched the vice-presidential debate on Wednesday evening (October 7th) with relatively low expectations. I figured that it would be much more civilized than the first presidential debate but would not have much new to offer. That’s exactly what I found. However, the next morning, President Trump announced that he would not participate in the October 15th debate due to its change from an in-person to a virtual event.

As we know, this change in venue was a response to the president’s contraction of the coronavirus. When he refused to participate in a remote presidential debate, the independent debate commission cancelled it. That means the vice-presidential debate may now be the last presidential event in this election cycle. We had better pay attention. So, another look is in order.

The normal kinds of fact checking that we discussed last week after the presidential debate will not serve us here. Sure, there were inaccuracies in the debate that can be classified as lies, fake news, etc. but there was nothing that I found to be completely outside the norms of political debates. Nor could various outlets determine a clear “winner” in terms of who persuaded new segments of voters to change their votes.

The morning after the debate, Bloomberg declared, “Harris Rips Trump Over Virus as Pence Hits Biden on Taxes, Court.” However, the candidates had only 90 minutes to debate 12 issues. We are living in very trying times right now and all the issues raised were very important—there simply wasn’t enough time to discuss almost any of them. This was compounded by both candidates using the classic politician strategy of completely ignoring certain questions. They pivoted instead to well-practiced talking points meant to appeal to voters.

While the debate featured far fewer interruptions than its presidential counterpart, one particular exchange led to Senator Harris’ thoroughly quotable line, “Mr. Vice President, I am speaking.” That line has since been printed on all sorts of political merchandise, including shirts and mugs.

I propose an alternative approach to trying to cram such a large list of topics into such a short time: let the debaters use their opening speeches to address why they deserve re-election to the position (in the case of the vice president) or why a replacement is necessary (Senator Harris). The rest of the debate would be confined to a combination of the issues that they raised in their opening speeches and one or two responses to public questions.

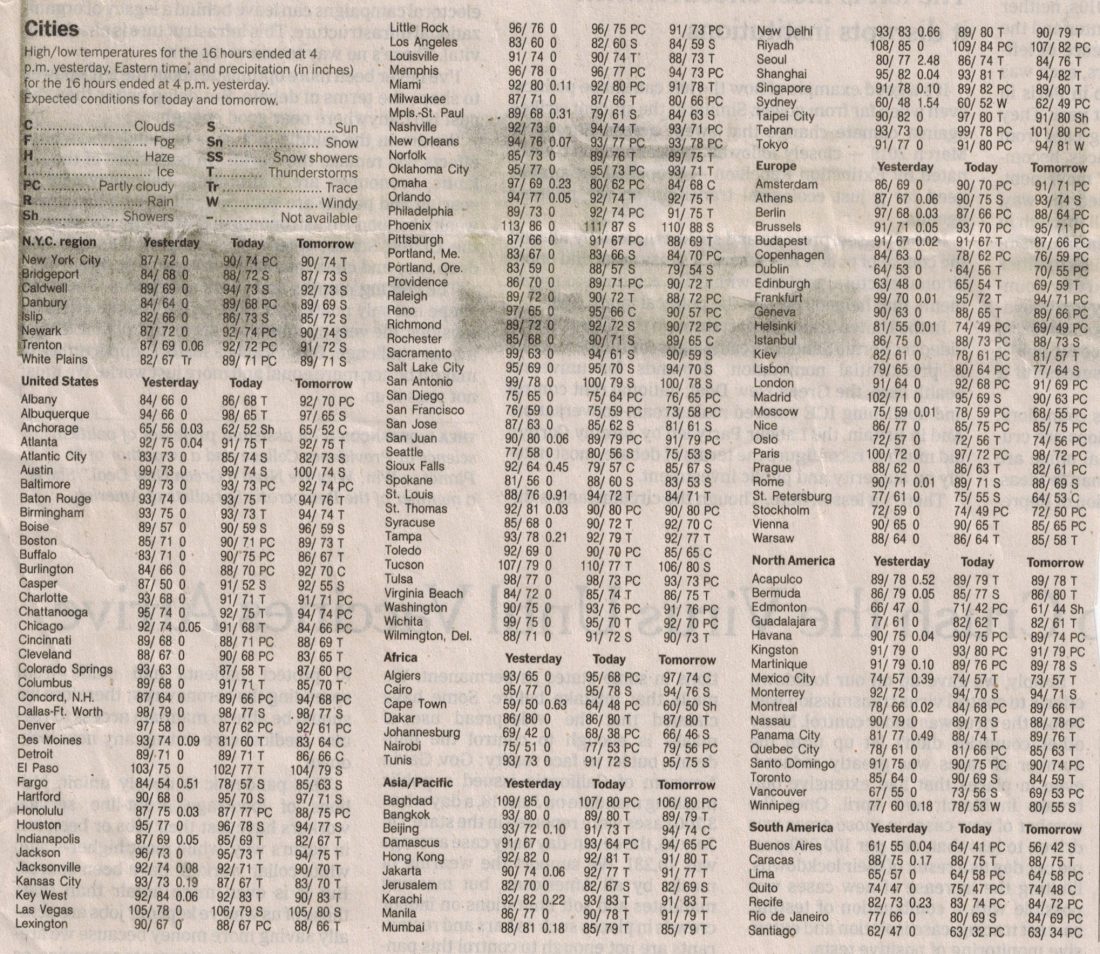

Since COVID-19 is the dominant event that has shaped our life over the last nine months, it was unsurprising that Senator Harris attacked the administration on its mishandling of the pandemic. Naturally, the vice president tried to defend the administration on how it has handled this issue. In both cases, the comparison of the pandemic’s impact on the US to that of other countries (normalized for population) was relevant.

The moderator asked Senator Harris what first steps Vice President Biden has planned, should he win the election. Her response was that their administration would immediately implement all of the relevant scientific recommendations regarding coronavirus. That includes mandates on mask wearing, keeping safely distanced, washing hands, and shutting down high-contagion establishments and activities.

VP Pence responded that this is the same policy that the administration has already been implementing and accused the Biden campaign of plagiarism. This was sort of a clever jab as it tried to remind voters that over his long career, Biden has had some issues with plagiarism. That said, there’s no secret about what would help quell the virus. Part of the tragedy of the situation is that the Trump administration knows very well what needs to be done but they continually refuse to do it. Senator Harris didn’t have time to respond and had to end the discussion with a sarcastic smile. Similar dynamics took place on many of the other issues.

When the moderator asked about the availability and timeline of a vaccine, Senator Harris responded that if the scientists certify a vaccine, she will be the first in line to try to get it. If, instead, President Trump were the only one vouching for the vaccine, she said, she would absolutely not take it. VP Pence claimed this meant she would be putting the American public in danger by questioning the effectiveness of the vaccine and discouraging people from taking it.

This sort of extreme politicization of the coronavirus is at the heart of the US failure in confronting the pandemic. Hopefully, once the election is over, we can focus on following the science and making progress in our country’s fight against this disease.

The iconic MAGA hat exemplifies the Trump administration’s unilateralist “America First” philosophy, to the detriment of global welfare

The iconic MAGA hat exemplifies the Trump administration’s unilateralist “America First” philosophy, to the detriment of global welfare