I am starting to write this blog two days after Super Tuesday. Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump came out way ahead of their competition as the leading candidates for the Democratic and Republican Party nominations for November’s election of the President of the United States. I promised to switch gears from Cuba to our upcoming presidential election, given how big of a role it will play in our immediate future. I have made a similar promise to my climate change class, where I am always trying to balance basic science with current events. In this case, much of that latter will revolve around the preliminary stages of the American presidential elections.

Up to now, climate change has hardly been mentioned in the election campaigns, but the terrain is very clear: both Democratic candidates, Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders, believe it to be a human-caused threat that requires major global mitigation efforts. They agree that these should be led by the US and have promised to continue and amplify President Obama’s work in this area. Meanwhile, the leading Republican candidates, Donald Trump, Ted Cruz and Marco Rubio, refuse to believe any of this and have vowed to overturn present policies and renege on international commitments to mitigate the impact. Marco Rubio, meanwhile, came back with the often-heard “I am not a scientist” argument, claiming that he is not qualified to determine the truth of climate change or whether mitigation efforts will cost American jobs. I took the opportunity to listen to the 11th Republican debate (Thursday, March 3, 2016) to find out if this assessment of the collective opinion is still valid; it is.

For the Democrats, the primary selection results so far have been a confirmation of the expected: victory for Hillary Clinton. As for the Republicans, the proceedings have come across as a disaster, with serious ramifications as to the future viability of the party in its present form. In the beginning of this process, during the first debate between more than 10 aspiring Republican candidates, the first question was a request for confirmation that each candidate was willing sign a pledge to support any Republican candidate if he (or she at the time) won the party’s nomination. The only candidate that refused to commit himself was Donald Trump. He later relented and signed a pledge to do so. In the last debate all three of his remaining opponents reaffirmed that promise.

But the campaign chair of one of the candidates has announced that he will not support Trump if elected. Mitt Romney, the 2012 nominee, and John McCain, the 2008 nominee, are urging all Republicans not to vote for Trump. Important party voices are calling for the creation of a third party. Name calling at the intellectual level of elementary school bullies is prevalent. It is certainly a show. Right now, this show has no direct impact on policy, but that could change radically in November.

United States residents are not the only ones alarmed. The European press is fully covering the turmoil with great apprehension. As many US publications have noticed, however, the Europeans shouldn’t be surprised. Donald Trump actually fits in very well within recent political trends in Europe.

Political figures like Italy’s Silvio Berlusconi have many similarities to Donald Trump. Not only was he a candidate for high political office but he actually served as Prime Minister four times. Meanwhile, Victor Orban, the President of Hungary, is very busy building fences to block the refugees that are seeking security in Europe. Jean-Marie Le Pen and his much more media-savvy daughter Marine Le Pen also fit into this category. The memorable French presidential election of 2002 saw the National Front candidate win the first round against the serving socialist Prime Minister Lionel Jospin only to then be defeated by the Conservative Jacques Chirac 82% – 18% because almost everybody in France was truly alarmed by Le Pen’s policies. In fact, just a few days ago, neo-Nazis were elected to the Slovakian parliament for the first time.

The cover of a recent issue of The Economist (February 27, 2016) came with a Trump caricature that reads “Donald Trump is unfit to lead a great political party.” This is a bit less ambitious than Mitt Romney’s outright declaration that Donald Trump is unfit to be the President of the United States.

The question immediately arises – who decides about a candidate’s fitness to be President (or leader of a party)? There are no exams and the only constitutional restrictions I know of for running for the office are age and “natural born citizenship”:

Age and Citizenship requirements – US Constitution, Article II, Section 1

No person except a natural born citizen, or a citizen of the United States, at the time of the adoption of this Constitution, shall be eligible to the office of President; neither shall any person be eligible to that office who shall not have attained to the age of thirty-five years, and been fourteen years a resident within the United States

Based on this text, Trump certainly seems more eligible than Canadian-born Ted Cruz, though both meet the age requirement. Ultimately, it will be up to the voters to make a decision; they are also the ones that must live with the consequences.

An extreme example of the mentality that is trying to raise Donald Trump into the American presidency can be traced (at least in my eyes) to 1933 Germany. The consequences of the decisions by the German electorate cost me my childhood and the murder of most of my family. Furthermore, it cost Europe and the world the lives of tens of millions of victims. Democracy is not yet very efficient at guarding against repetition.

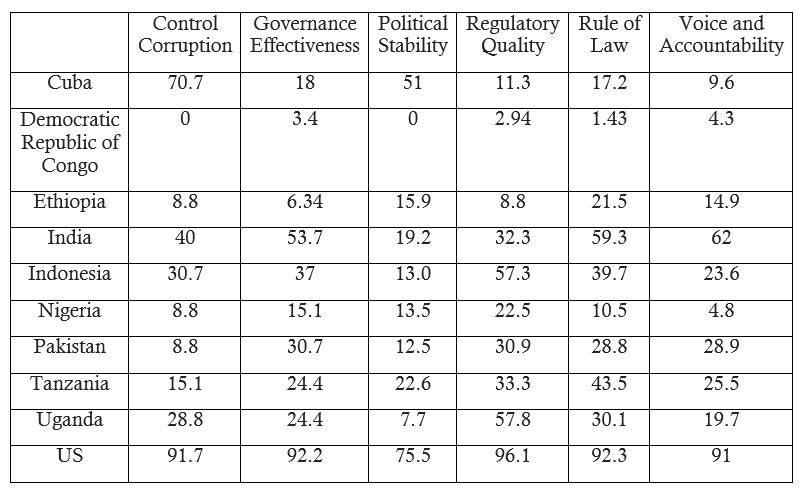

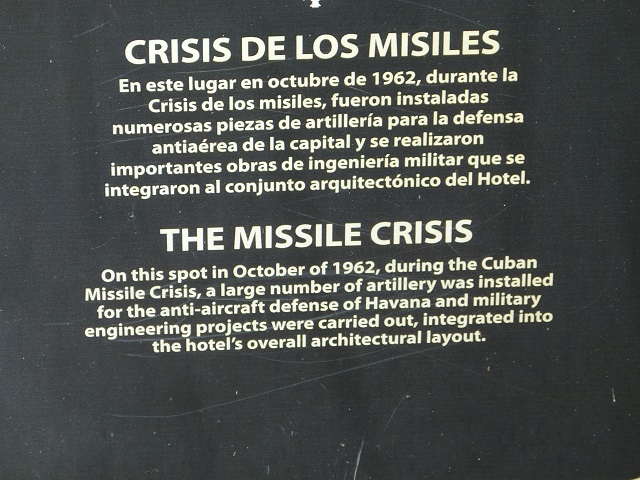

One often-discussed way to guard against candidates like Donald Trump is to censor candidates. There are huge pitfalls in establishing such a process that can be easily gamed. Two countries come to mind – Cuba and Iran. As we discussed last week, under The Economist’s Democracy Index, both countries’ governments are termed authoritarian. Iran comes in at 156th place on the list, with a democratic index of of 2.16, and Cuba is number 129 on the list, with a score of 3.52. The main components that drive both of them down are Electoral Process and Pluralism; that said, they do not rate well in the other criteria either. Guest blogger Jake Levin described the situation in Cuba (February 16, 2016):

Still, according to the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance, the average Cuban election sees more than 95% participation. These are non-mandatory, and there is little evidence that there are repercussions for citizens who choose not to vote. The process is conducted in a town-hall nominating format, with municipal candidates presenting their credentials to their constituents and voters approving or denying them in nominating assemblies. Provincial candidates go through multiple vetting rounds at the local level. Political scientists and philosophers have debated the democratic or non-democratic nature of the political process for decades – while likely not a system of which John Dewey would approve, it is a form of democracy.

A few days ago, elections were held in Iran. Here are some of the highlights:

There were 54,915,024 registered voters (in Iran, the voting age is 18). More than 12,000 people filed to run for office.[5] Nomination of 5,200 of candidates, mostly Reformists,[6] were rejected by the Guardian Council and 612 individuals withdrew.

Electoral system

The 290-seat Islamic Consultative Assembly has 285 directly elected members and five seats reserved for the Zoroastrians, Jews, Assyrian and Chaldean Christians and Armenians (one for Armenians in the north of Iran and one for Armenians in the south).[7]

The 285 directly elected seats are elected from 196 constituencies, which are a mix of single and multi-member. In single-member constituencies candidates must receive at least one-third of the votes in the first round. If no candidate passes this threshold, a second round is held with the two highest-vote candidates. In multi-member constituencies, voters cast as many votes as there are seats available; candidates must receive votes from at least one-third of the voters to be elected; if not all the seats are filled in the first round of voting, a second round is held with twice the number of candidates as there are seats to be filled (or all the original candidates if there are fewer than double the number of seats).[7]

Voters must be Iranian citizens aged 18 or over, and shall not have been declared insane.

Qualifications

According to Iranian law, in order to qualify as a candidate one must:[7]

- Be an Iranian citizen

- Have a master’s degree (unless being an incumbent)

- Be a supporter of the Islamic Republic, pledging loyalty to constitution

- Be a practicing Muslim (unless running to represent one of the religious minorities in Iran)

- Not have a “notorious reputation”

- Be in good health, between the ages of 30 and 75.

A candidate will be disqualified if he/she is found to be mentally impaired, actively supporting the Shah or supporting political parties and organizations deemed illegal or been charged with anti-government activity, converted to another faith or has otherwise renounced the Islamic faith, have been found guilty of corruption, treason, fraud, bribery, is an addict or trafficker or have been found guilty of violating Sharia law.[7] Also, candidates must be literate; candidates cannot have played a role in the pre-1979 government, be large landowners, drug addicts or have convictions relating to actions against the state or apostasy. Government ministers, members of the Guardian Council and High Judicial Council are banned from running for office, as is the Head of the Administrative Court of Justice, the Head of General Inspection, some civil servants and religious leaders and any member of the armed forces.[7]

The final results are not yet in because a second round is still needed for few of the assembly seats, but the overall assessment is that the reformists did very well. Laura Secor provided a detailed description of the outcome in the New York Times (March 5, 2016).

I’m sure we are not about to directly emulate Iran or Cuba’s practices, but discussions are certainly in order to talk about mechanisms to control the kind of candidates that are applying for our trust. We are currently placed at the bottom (#20) of the Democracy Index’s “full democracy” section. Any candidate-vetting process will obviously reduce our score in “pluralism,” moving us down to the “flawed democracy” category. We’ll need to decide whether sparing ourselves the votes on disastrous candidates such as Donald Trump is worth such a downgrade.